Helena Frank: Turn-of-the-Century Translator in JQR's Old Series

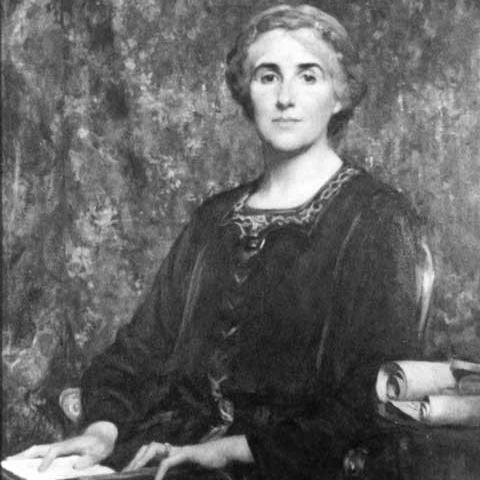

In honor of Women’s History Month, JQR is highlighting one of its earliest women contributors, the fascinating but now mostly-unknown Helena Frank

Richard Wilson Lake Albano (1762), Paul Mellon Collection, National Gallery of Art.

Founded in 1889, JQR spent nearly two decades in England before moving to Philadelphia in 1908 under new editorship. Peruse the contents of these early issues—now called the Old Series—and you’ll find Jewish literature in English translation among the journal’s early output. Translations ranged from Talmud to contemporary poetry and drew from Hebrew, Yiddish, Russian, and more. Translators worked alone or in collaboration, presenting literature with accompanying scholarly analysis or without. There are more contributions by women in JQR’s fin-de-siècle issues than you might expect, and most are translations; although these women translators were few, they were prolific, creating a strong presence in the journal. This Women’s History Month, we are spotlighting the poetry translations of Helena Frank, a trailblazer in Jewish literature. All of her contributions are available open access.

Almost no English-language scholarship exists on Helena Frank, but the poet Jacob Glatstein (1896–1971) wrote a short biography of her in Yiddish in 1970, which Aharon Varady has translated into English, accompanied by an introduction containing additional archival data. It seems that Frank was born in England in 1872 to a German father and British mother. An ardent advocate for Yiddish, she undertook her first book-length translation in 1906 when the Jewish Publication Society asked her to translate Stories and Pictures by I. L. Peretz (Philadelphia, 1906). Her subsequent books brought Yiddish literature by a variety of authors to English readers for the first time, including the anthology Yiddish Tales (Philadelphia, 1912) and Morris Rosenfeld’s Songs of Labor and Other Poems (translated with Rose Pastor Stokes, Boston, 1914).

Before these book publications, though, Frank published poems in journals, including JQR. Five issues of JQR between 1902 and 1907 featured her contributions, and her first was expansive: nineteen poems from Simon Frug’s Yiddish “Lider un Gedanken,” spanning thirty-six pages in the journal’s April 1902 issue. Frug, a Russian and Yiddish poet, rose to fame after his poem “The Goblet” was translated from Russian to Yiddish and became a popular song; the translator of “The Goblet” into Yiddish was none other than I. L. Peretz, whose poetry Frank would translate into English in her first book in 1906.

In the selections of Frug’s poetry that appear in JQR, the natural world serves as a metaphor for, and distraction from, personal suffering. Inspired by Frug’s experiences of the Russian pogroms of the early 1880s, poems like “Sand and Stars,” “Nature,” and the trio “Spring Songs,” “Summer Songs,” and “Autumn Songs” thematize the juxtapositions of cosmic and psychic, of Jewish joy and Jewish pain. Frank’s second JQR translation, published in November of the same year, was “The Jewish May,” a Yiddish poem by Morris Rosenfeld, which uses the motif of the seasons in a similar way. This JQR translation anticipates her 1914 publication of Rosenfeld’s Songs of Labor and Other Poems.

Frank’s next contribution to JQR followed soon after, in January 1903, this time in collaboration with Alice Lucas. A British poet and translator active in the London Jewish community, Lucas was also the sister of one of JQR’s founding editors, Claude Montefiore. She is best known for The Jewish Year: A Collection of Devotional Poems for Sabbaths and Holidays throughout the Year (London, 1898), which features liturgical poetry in English translation alongside original poetry. Like Frank, Lucas was a frequent contributor of translations to JQR’s Old Series. Their collaborative effort was Simchas Torah (The Rejoicing of the Law), from the Yiddish of J. L. Gordon, reflecting Lucas’s continued interest in liturgical poetry.

Frank’s final JQR translations were poems by Hayim Nahman Bialik. The first, in October 1906, is “'Al Shechitah,” which she translated into English “from the Yiddish of N. Byalik’s version of a Hebrew poem by himself.” Soon after, in April 1907, JQR published “N. Byalik and His Poems. Translated from the Writer's Russian MS,” a collaboration between Frank and one “B. Ibry.” The essay contains a biography and literary analysis of Bialik by Ibry—whose identity is not readily identifiable—with translations by Frank throughout. Ibry explains (p. 447) that Frank’s earlier translation of Bialik in JQR inspired Ibry’s research into Bialik’s life and work:

And it is only quite lately, thanks to the publication by the Jewish Quarterly Review (October, 1906) of a translation of his Yiddish poem on the pogroms, that some interest has been aroused here in Byalik’s personality and his other works.

Ibry credits Frank and JQR with bringing Eastern European Jewish writing and experience to new audiences.

It is difficult to assess the contributions by women to the early years of JQR. In the Old Series, many authors provide only their first initial rather than a full name, meaning that female translators and scholars are not always readily identifiable from a quick skim through the tables of contents. Helena Frank’s JQR publications reveal the early work that informed her later books and provide a glimpse into a deeply interconnected turn-of-the-century Jewish literary community, in which poets translated themselves and other poets, and translators collaborated with one another and with scholars. Frank’s English translations, in JQR and beyond, helped open this literature onto the anglophone world.

Sources:

Jacob Glatstein, “Figures in Need of Rehabilitation: Helena Frank,” with translation and introduction by Aharon Varady, In geveb (2023), accessed March 25, 2025.

Nadia Valman, Jewish Women Writers in Britain (Detroit, Mich., 2014): 50–52.