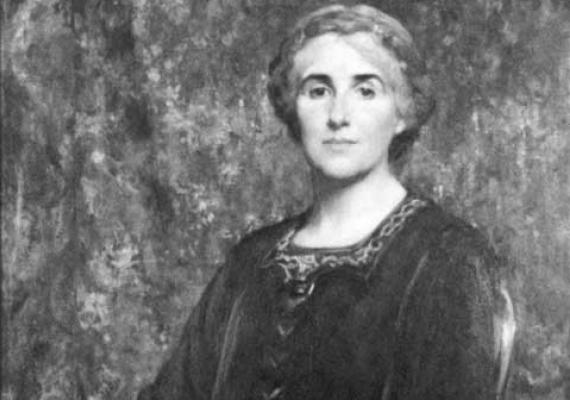

Nina Davis Salaman (1877–1925)

It was the work of genius (the spirit of God) to create a religion which, with the development of mind, was capable of covering the inevitable varieties of individual thought. (Davis, “An Aspect of Judaism in 1901,” JQR 13.2 [1901]: 241–57)

For Women’s History Month, JQR draws your attention to a remarkable fin-de-siècle character: Nina Davis. British-born Davis was a regular contributor to the old series of JQR—her byline as author, as coauthor, and most commonly as translator, appeared 29 times in the journal’s pages between 1895 and 1901.

Old Series JQR, it probably goes without saying, was no place for young women. They are rare birds whose contributions to the journal were confined almost entirely to translation, but within that cohort Davis was the most prolific. The company she kept on those tables of contents were scholars of such legendary learning that they are all virtually still household names (well, in certain households). Every issue bristled with essays, reviews, and erudite notes by Cyrus Adler, Solomon Schechter, Alfred Neubauer, Heinrich Graetz, Wilhelm Bacher, R. H. Charles, David Kauffmann, Israel Abrahams, Ignaz Goldziher, Claude Montefiore, Alexander Kohut, and Moshe Friedlander—just to name a few—and they presumably suffered no fools.

It is especially impressive in this context that her first piece was published in 1894 (JQR 7.1: 141–44), when Davis was only 17 years old! “The Ideal Minister of the Talmud” is a poem of her own composition set in response to the question asked by the rabbis in the Gemara (bTa‘an 15a–16b), “Who is qualified [to minister to God before the Torah]?”

His lips are steeped in wisdom handed down

In golden links unbroke from sire to son,

Long treasured race-traditions old and dear,

To be preserv'd through ages yet unborn.

Speaking in glowing words of metaphor,

He shows the beauty of their ancient faith.

With echoes of Ben Sira, she praises her ideal man, a scholar steeped in empathy, a clarion from the God of Israel to Jew and human alike.

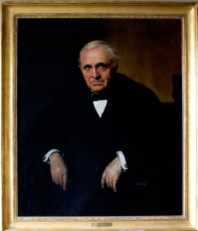

Davis’s frequent publications, often translations of Judah Halevi, were on a few occasions coproduced with her sister Elsie. Her connection to JQR seems to have grown from association with the (Kilburn) “Wanderers,” a group of Anglophone Jewish intellectuals in the 1880s. She was close friends with members of the group, especially Israel Zangwill and Israel Abrahams. For a wonderful discussion of the cabal see Israel Abraham’s encomium to it and its brilliant charismatic “Johnson”—Solomon Schechter (reprinted from the London Jewish Chronicle in The Reform Advocate, January 15, 1916). Davis no doubt both contributed to and learned from their committed yet free thinking spirit vis-à-vis tradition. Abrahams encouraged her translations of medieval Hebrew and it was Zangwill who introduced her to Mayer Sulzberger (pictured below); in 1901 the Jewish Publication Society published a collection of her work, Songs of Exile by Hebrew Poets.

1901 was the same year she married physician and ostrich feather heir Redcliffe Nathan Salaman. Though rearing six children seems to have kept her from the pages of JQR in the early years of the twentieth century, she remained a scholar and activist throughout her life. Davis fought unconventionally for what to her were deeply traditional and conservative values: Judaism, family, and Torah. She was a suffragette, both for women in England and also for women’s voices in the synagogue. She was a Zionist who in 1916, according to Todd Endelman’s biographical entry in the Jewish Women’s archive encyclopedia, “published one of the first English translations of the Zionist anthem ‘Ha-Tikvah’ and later wrote the marching song for the Judeans, the Jewish regiment that took part in the British conquest of Palestine at the end of World War I.” He goes on to note: “More daringly, on Friday evening, December 5, 1919, she became the first—and only—woman to preach in an Orthodox synagogue in Britain when she spoke on the weekly portion to the Cambridge Hebrew Congregation.”

1901 was the same year she married physician and ostrich feather heir Redcliffe Nathan Salaman. Though rearing six children seems to have kept her from the pages of JQR in the early years of the twentieth century, she remained a scholar and activist throughout her life. Davis fought unconventionally for what to her were deeply traditional and conservative values: Judaism, family, and Torah. She was a suffragette, both for women in England and also for women’s voices in the synagogue. She was a Zionist who in 1916, according to Todd Endelman’s biographical entry in the Jewish Women’s archive encyclopedia, “published one of the first English translations of the Zionist anthem ‘Ha-Tikvah’ and later wrote the marching song for the Judeans, the Jewish regiment that took part in the British conquest of Palestine at the end of World War I.” He goes on to note: “More daringly, on Friday evening, December 5, 1919, she became the first—and only—woman to preach in an Orthodox synagogue in Britain when she spoke on the weekly portion to the Cambridge Hebrew Congregation.”

Her last work, a collection of translations of the poetry of Halevi into English, was published in 1924. Nina Davis Salaman died in 1925.