Q&A: Gender and Jewish Philosophy with Sarah Zager

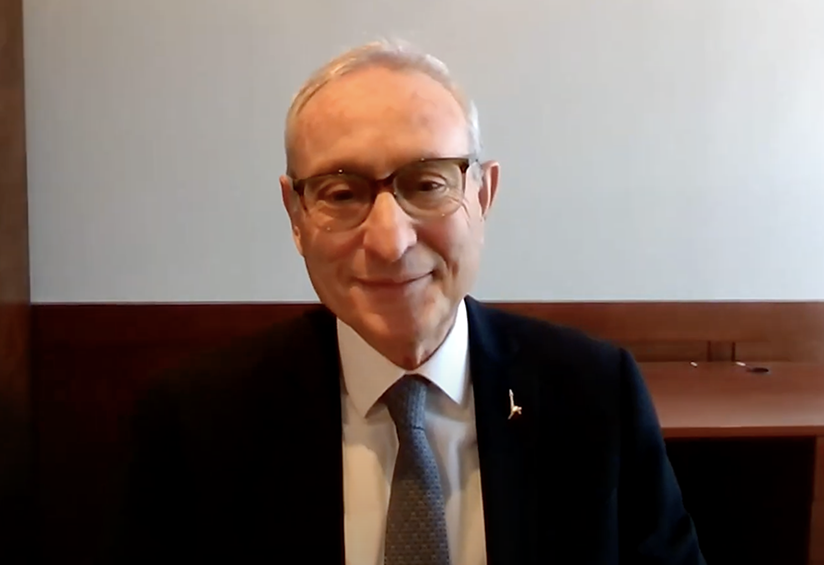

Meet the instructor of our upcoming online mini-course.

Current fellow Sarah Zager is an award-winning teacher known for clarity and accessibility in taking up complex and thorny issues, a recent PhD from Yale, and at work on a book exploring how Jewish philosophy can contribute to today’s debates about virtue ethics.

As she is gearing up to teach an online course on gender and Jewish philosophy for us, we asked her a few questions about the subject and her approach to it.

What does the category of gender have to bring to the study of philosophy? How does that picture change when talking about Jewish philosophy as opposed to the general western philosophical canon?

Gender is one of the fundamental social categories that shapes our world—it influences how people relate to one another and the metaphors and images that we use to make sense of the world around us. All of this can and should be analyzed philosophically. Any philosophical approach that ignores gender is going to produce a picture of the world that is partial at best, and seriously misleading at worst. The same goes for reading philosophical texts—philosophical texts themselves use gendered terms, ideas, and metaphors. If we want to understand what those texts are saying, and engage critically with their ideas, we need to think about how gender works within them.

Doing that isn’t simply a matter of finding places where women are mentioned or adding more women to the philosophical canon (though of course we need to do this too!)—studying gender means studying masculinity as well as femininity, it means studying both cis-gendered identities and non-cis ones.

Jewish philosophy sits at the intersection of three gendered traditions of thought: philosophy, Judaism (by which I mean the wide swath of Jewish texts and practices on which Jewish “thinkers,” broadly construed, draw), and Jewish philosophy (by which I mean the narrower range of Jewishly-inflected texts that explicitly announce themselves as philosophical). So, thinking about gender in Jewish philosophy requires thinking about how gender operates in all three of these strands, before looking carefully at how a given Jewish philosophical text weaves them together.

Thinking seriously about gender and Jewish philosophy also requires finding Jewish philosophy in new places and new texts. In thinking about this, I’m drawn to the philosopher Stanley Cavell’s idea that some forms of philosophy, especially twentieth-century philosophy, are marked are by a kind of modernism that challenges the tradition’s formal constraints. Cavell writes that “it is the task of the modernist artist to show that we do not know a priori what will count for us as an instance of his art.” These new modernist contributions are works that we could not recognize as members of the genre before encountering them.

I like to think of Jewish feminist philosophy as “modernist” in this Cavellian sense. Jewish feminist philosophy does not always present itself as philosophical: Judith Plaskow’s work can look more like theology or exegesis, Mara Benjamin’s work has sections that read more like creative nonfiction or an essay than a treatise on Jewish thought, and Nima Adlerblum, an early twentieth-century figure I’m working on, formulates her new “approach to Jewish philosophy” through memoir. Each of these works prompts readers to find Jewish philosophy in places, and in forms, where they did not think it possible to find it.

Can you say something about your personal and intellectual path toward the study of Jewish philosophy?

My path to Jewish philosophy is both very simple and very complicated. The simple story is that I read Moses Mendelssohn’s Jerusalem in an “Introduction to Judaism” class I took on a whim in college, and ended up hooked. In a certain way, I jumped into reading Mendelssohn and never looked back.

I have always been drawn to philosophical work—to thinking in a way that is structured primarily by argument—but I have nagging worry about the way philosophical debate assumes a kind of universality (we’re talking about “the good” or “the right” for everyone, not just for any specific group of people or any given situation). That stance prevents it from really getting at what it’s like to live as a person who is located in a particular time and place, or a particular body. Jewish philosophy is trying to think about this puzzle too—because it wants to be philosophical, to participate in that form of structured argument, while still being deeply interested in a kind of particularism.

The longer story is that there are lots of ways in which my biography doesn’t match the usual pattern of a scholar of Jewish philosophy. I grew up in a tiny, but very lovely, Jewish community in Albuquerque, New Mexico. We were pretty isolated from a lot of Jewish intellectual life—our community didn’t really prioritize Jewish text study, and I certainly didn’t know that Jewish studies could become a career. Growing into the field has meant being continually surprised by how capacious Jewish studies can be for addressing concerns that seem like they lie outside of its usual orbit. Finding that space within the field can be challenging, but it’s also one of the most rewarding parts of my work.

I came to studying gender and Jewish philosophy explicitly much later. For a long time, I really didn’t feel a gap between the dead, mostly white, men whose work I studied. They were asking questions that felt pressing to me, and I mostly didn’t notice anything else. That changed later in graduate school, when I began to write about my own experience with infertility, and to think about its relationship to both Jewish texts and recent work in feminist philosophy. An effort to think through my own experiences introduced me to how powerful a gendered analysis of Jewish philosophy can be. These analyses not only help us read the canon of Jewish philosophy better, they open up new ways of understanding the world around us.

Your work on virtue ethics and other models of good and just behavior makes a very intentional intervention in today’s discourse. How easy or hard is it to find the intersection between high philosophical texts and social media—between Mendelssohn and Twitter?

I think there’s sometimes a feeling that “high philosophical texts” exist on some different metaphysical plane than daily life. I don’t think that’s true. Philosophy is a tradition (or better, a group of traditions) of structured ways of dealing with questions that we all encounter: What is real? What is actually important? How much can I really know about someone else? What do I owe them even if I can’t really understand everything about them? These questions come up all the time on Twitter, on other social media (I don’t get TikTok yet!), and in other quotidian interactions.

Mendelssohn is actually a really instructive example here. Mendelssohn’s career was punctuated by episodes in which he was unwillingly called to public intellectual duels. In some of these episodes, Mendelssohn’s private correspondence was shared publicly in ways that he did not want or expect. Mendelssohn’s writing from the time reflects his thinking about these issues, and reading his reflection can give us insights into our own challenges with public discourse about politics, identity, and religion.

For a person who can’t make it to the mini-course but is curious about the topic, or for someone who takes the course and wants more, do you have any suggestions for related reading?

There is so much to read here, but a few suggestions:

Mara Benjamin’s The Obligated Self: Maternal Subjectivity in Jewish Thought has created a new path forward for thinking about gender, Jewish philosophy, and care. It’s also beautifully written and quite accessible.

There’s also Sarah Imhoff’s The Lives of Jessie Sampter: Queer, Disabled, Zionist, treating a thinker whose works are rarely read. It too does a great job of integrating standard academic writing techniques with other, more adventurous styles.

I also love Nima Adlerblum’s autobiography Memoirs of Childhood: An Approach to Jewish Philosophy. Adlerblum was the daughter of the prominent Orthodox rabbi Hayyim Hirschenson and also a graduate student of John Dewey’s at Columbia. Memoirs of Childhood is a reflection on her childhood in Palestine, interspersed with her reflections on how her childhood experiences shaped her philosophical approach.