Secundus the Silent and the Vanishing Seduction of Beruriah

After the great Rabbi Meir asks his student to seduce his wife to teach her humility, the Talmud’s only named female Torah scholar commits suicide. Moshe Simon-Shoshan reassesses the legacy of this sordid tale.

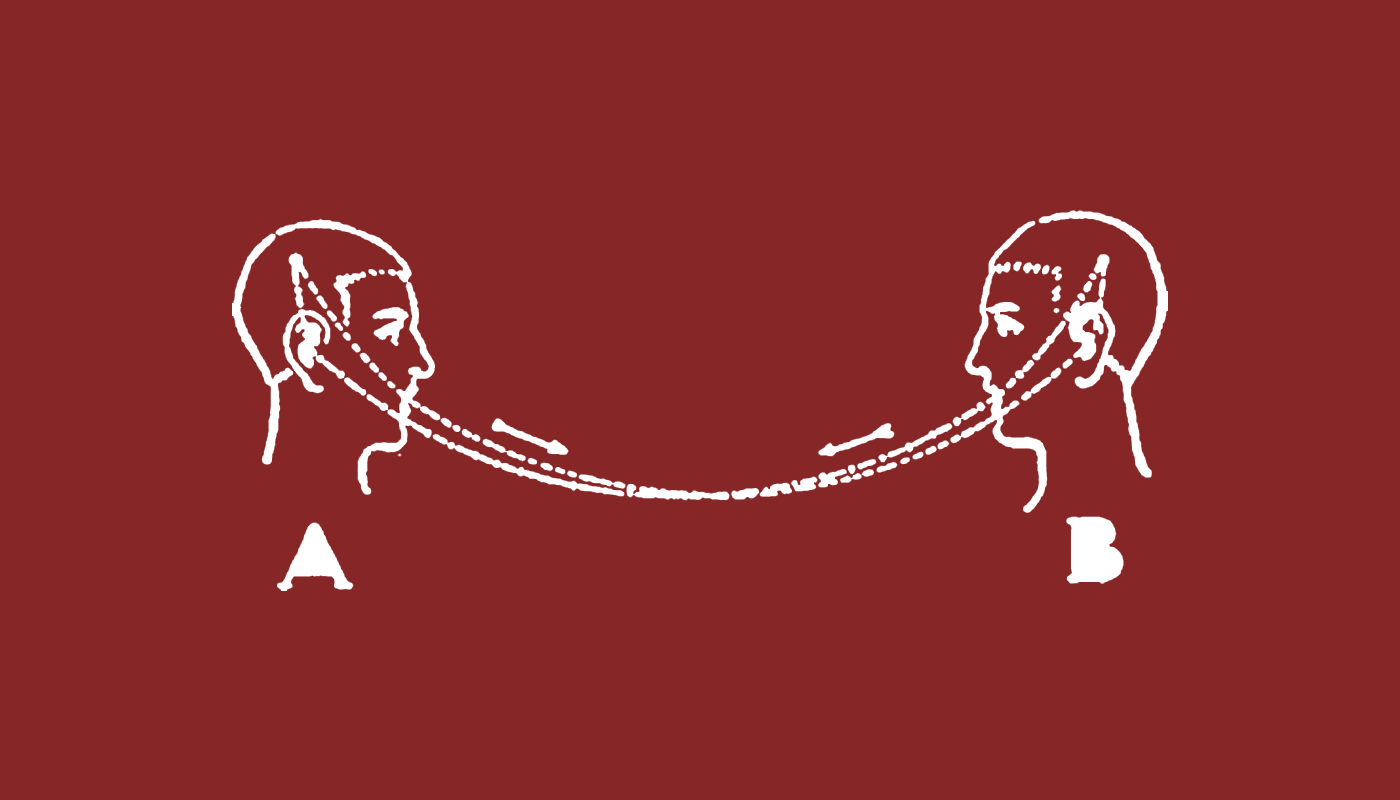

Secundus the Silent was a first-century Greek philosopher who in order to prove his assertion that women were incapable of chastity, undertook successfully to seduce his own mother. Though he revealed his identity to her while the two were in bed together—before consummating the affair—her willingness, and resultant shame, led her to hang herself. Though Secundus’s point was carried, his growing sense of the dishonor of his action and its fallout led him to take a vow of silence about the event; thus his epithet. (Amalek-like, his discretion is belied by the wide circulation of the tale.)

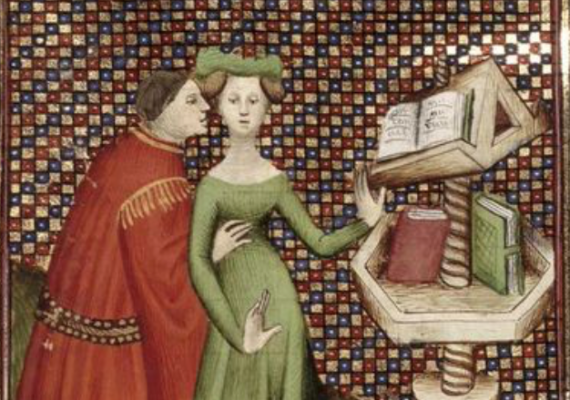

Moshe Simon-Shoshan mentions this text in the course of his fascinating essay on a similar tale about Rabbi Meir and his scholar-wife Beruriah (JQR 110.3). He begins with Rashi’s famous expansion of the Bavli’s elliptical mention of a ma‘aseh de-Beruriah (Beruriah incident; bAZ 18) which explains that the “incident” alludes to Beruriah’s seduction by a student of her husband. The great Meir incites his disciple to seduce her as a way to prove to his wife her error in believing women were not inherently “lightheaded.” Meir’s minion comes on strongly to Beruriah until she eventually gives in; in her disgrace she commits suicide.

Simon-Shoshan intervenes in the scholarship in two ways. First he argues that Rashi’s story, though it does not appear until the early 14th century, likely hews closely to the tale that subtends the original talmudic allusion. He lays out his argument in lucid terms, positing a series of theories about the tale’s origins then going through the sources and thought process by which he dismisses or adopts them. He shows his work, in other words, and it is illuminating to watch his scholarly process. The second half of the paper pushes the reader to see the episode not as another denigration of women by a hegemonic patriarchy, but as a rather pointed reassessment of Meir's actions and the moral complexity of “the rabbinic project itself.”

Being the Talmud’s only named female scholar, Beruriah has attracted seas of scholarly ink, but the subtext of Simon-Shoshan’s essay is the history of the unseen and the unwritten. He traces a vapor trail of prudish apologetics that has clouded this tale for centuries, reducing it to an allusion in rabbinic literature ab ovo. No rabbi could behave like this, and thus the story is not retold, it is instead looked politely past. Yet somehow it has persisted despite this official silencing—an oral scholion to the Oral Torah. As Simon-Shoshan reads it, the low-hanging misogyny is not the most trenchant read of the tale, nor does prurience alone account for its particular persistence. Like Secundus, the tale’s complexity, and thus its failed silence, is wrapped up in the nagging moral ambiguity of its pious perpetrators.

Read Simon Shoshan’s full article “The Death of Beruriah and Its Afterlife: A Reevaluation of the Provenance and Significance of Ma'aseh de-Beruriah” in the fall issue of JQR (JQR 110.3 ).