SIMS-Katz Fellow Sacha Stern Initiates Us into the Art and Science of Medieval Timekeeping

Looking for dating advice? Read on!

Are medieval manuscripts sexy?

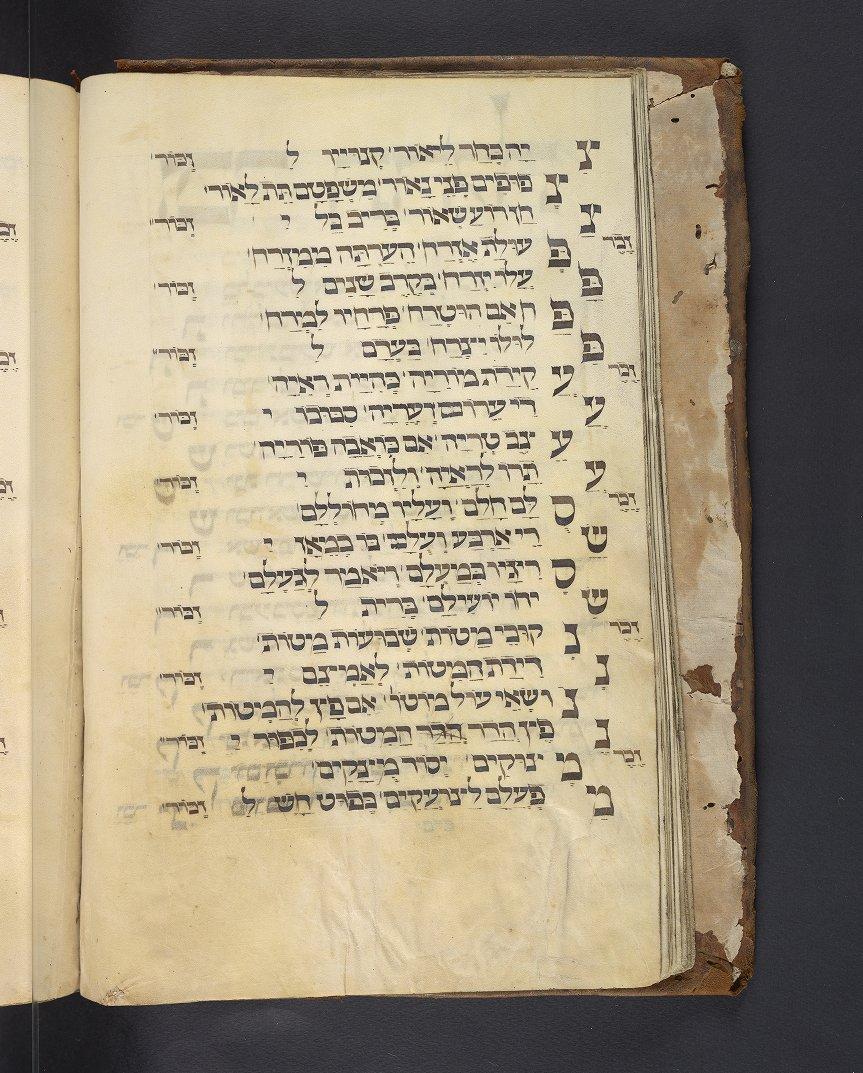

This question is more than just a provocation. It is part of the allure of the luminous parchment skin of a manuscript that it makes you want to reach out and feel its tough yet tender surface. It is part of the appreciation of how well put together a manuscript is, how carefully its leaves have been prepared and gathered together into quires, how the layout of each page is ruled and lined in careful order, how the scribal hand speaks to the eye as well as the ear in its tailored shapes, sizes, colors and illuminations. It is in the mystique of an inscrutable body of writings, whose language, logic, and hidden meanings are so daunting to grasp.

Professor Sacha Stern, an Oxford-trained fellow of the British Academy and professor of rabbinic Judaism at the University College London, did not explicitly ask this question in his brilliant, meticulous, at times funny, and stimulating lecture “Dating Saints: A Remarkable Hebrew Compendium of Astronomy and Calendars” (February 18, 2025, Class of 1978 Orrery Pavilion of the Van Pelt Library at Penn). It is, however, implied by the sly word play in the title of his talk and in the passionate manner in which he methodically communicated his joy and skill reading one of the Kislak Center’s most prized manuscripts: LJS 57. How then does one get to know medieval manuscripts, figure out how to date them, learn where they come from, and spend time basking intimately in their effulgence?

Sacha Stern’s presentation marked the eighth time the Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies (SIMS) & the Herbert D. Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies (Katz) Distinguished Fellow’s Annual Lecture in Jewish Manuscript Studies occurred. The purpose of the SIMS-Katz Fellowship, for those new to this stellar program, is to help advance the mission of the Schoenberg Institute for Manuscripts Studies. As its late founding director William Noel defined it, this mission is “to bring together people, technology, and manuscripts” in innovative, open, and creative ways. One component of this annual program is the public lecture, sponsored by Penn’s Jewish Studies Program in partnership with the Katz Center and the Penn Libraries.

The goal is to match a distinguished scholar with an exceptional medieval Hebrew manuscript in Penn’s collection. This year went swimmingly. Success happens when you introduce one of the world’s greatest scholars of premodern calendar systems—as Penn’s prize-winning faculty member Simcha Gross made clear in his introductory paean to Sacha Stern—with one of the most prodigious, beautiful exemplars of late medieval Jewish timekeeping. The main focus of Stern’s talk, Laurence J. Schoenberg manuscript 57 (LJS 57), is a “remarkable Hebrew compendium of Astronomy and Calendars” produced in Catalonia in the Kingdom of Aragon in northeastern Spain in the latter half of the fourteenth century.

Arcane to some perhaps but hardly unknown, Nicholas Herman, the Laurence J. Schoenberg Curator at SIMS, pointed out in his opening remarks that LJS 57 has twice been exhibited in recent years: at “The Sassoons” exhibition at the Jewish Museum in NYC in 2023 and at the Getty Museum’s “Lumens: The Art and Science of Light” exhibition in Los Angeles in 2024. Thanks to the visionary efforts of Laurence J. Schoenberg, the previous owner and donor of this manuscript, and the founder of SIMS, LJS 57 now may be viewed in its entirety online in a completely open and unrestricted. Multiple online videos of its great artistry and scientific data have been made about it. LJS 57 also has also been the subject of Coffee with a Codex, a regularly featured online, informal presentation of rare manuscripts from the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts at the Penn Libraries, created by SIMS Curator of Digital Humanities, Dot Porter.

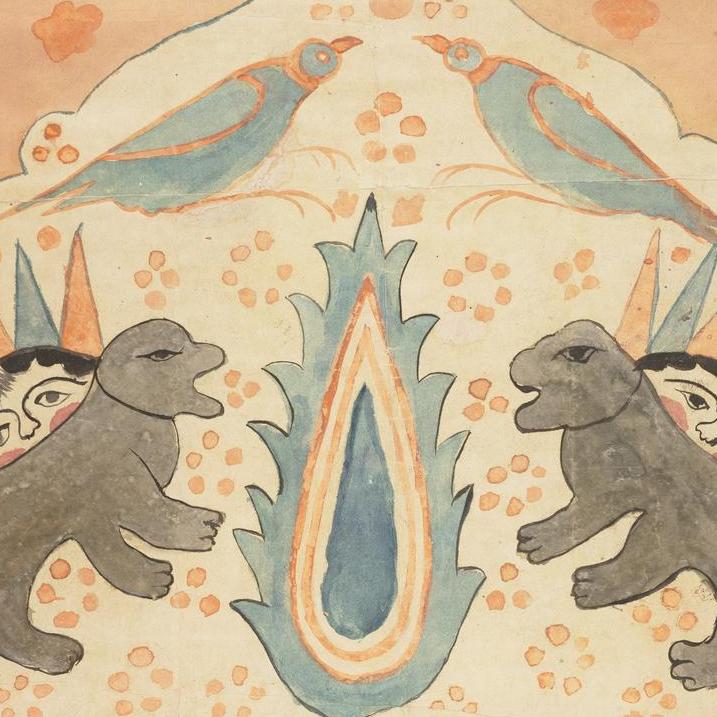

Despite the relative fame of LJS 57, in Stern’s expert hands it became a nearly blank canvas upon which he painted new scholarly perspectives about the manuscript, its contents, its artistry, and its historical significance. He revealed new meanings in the manuscript’s pervasive decorative features, mise-en-page, and beautiful illustrations that have eluded others. He raised probing questions about what he called the manuscript’s dialectical relationship between aesthetic creativity—its stunningly beautiful (and expensively produced) appearance—and its abundant tables of seemingly dry scientific data. He asked if the manuscript’s artistic expressions are “an effort to liven up the science or is the science a framework for creativity?" He gently corrected previous cataloging descriptions, arguing that the manuscript was produced in the fateful year of 1391 in Catalonia, not 1361. He pointed out the erroneous description of LJS 57 as a treatise on the calendar and leap year when in fact it concerns solar and lunar astronomical cycles which track and date new moons and eclipses. He also rejected as impossible the previous identification of the third of ten discrete works in the compendium as a medieval Hebrew translation of Ptolemy’s second-century c.e. Almagest, a treatise on astronomy. Rather, he explained, it was an otherwise unknown medieval astrological work attributed to him. At the same time, he made sure to explain that both astronomy and astrology were considered scientific and embraced widely by many medieval Jewish thinkers. Among them may be counted the famed twelfth-century Spanish biblical commentator Abraham Ibn Ezra, whose own study of the zodiac is second in the order of the contents of the manuscript, just ahead of the pseudonymous Ptolemy.

Most striking perhaps was his unstated critique of an accepted major historical difference between medieval Christian and Jewish manuscript production. Stern undermined the long-held view of Malachi Beit-Arie that Christians produce manuscripts in professional scriptoria while Jews, by contrast, served for the most part as their own copyists of manuscripts for their own private use. Through a careful comparison of LJS 57 with a group of roughly contemporary individual manuscript leaves preserved in the Vienna State Library (MS Vienna Hebrew 132), Stern argued that they are evidence of Jews engaged in “a large-scale production or enterprise, a commercial operation.” These nearly identical leaves to what we find in LJS 57 constitute “leftovers” of an incomplete book, prepared individually by multiple hands in stages for book (codex) production. LJS 57 is the fully realized product: a completed codex book. It is in poorer condition than the leaves preserved in MS Vienna Hebrew 132, but that is not to be viewed as a defect. Its wear and tear are actually historically meaningful signs of its use. LJS 57 was not simply a book-lover’s trophy to be displayed as a prestigious sign of wealth and learning but in fact was frequently handled and consulted for practical purposes. The need for such tools, Stern argued, demonstrates the existence of “factories,” as he called them, of Hebrew manuscript production to generate multiple copies of important works for sale and distribution.

No authority was left unchallenged, including himself. Stern publicly revised his own published scholarship (“Christian Calendars in Medieval Hebrew Manuscripts,” in Medieval Encounters 22 [2016]: 236–65). He shared that, thanks to his SIMS-Katz Fellowship term of research, he now recognizes that the phenomenon of Christian liturgical calendars written in Hebrew by Jews are not restricted geographically to medieval Ashkenaz, that is northern France and Germany, in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. In Penn’s LJS 57, he discovered a unique, magnificent exemplar of Jews tracking Christian festivals such as market days, feasts, and saint days well beyond those areas, suggesting it was a panwestern European Jewish phenomenon. At the same time, he meticulously compared and pointed out differences between the Catalonian and Ashkenazic Hebrew calendars of Christian liturgical days. Among the fascinating examples were Arabic numerals written in Hebrew letters in LJS 57 that when read are the transliterated form of the Catalan word for the equivalent number!

Why you may ask would Jews create calendars in Hebrew of Christian holidays? A good question, and one that Stern raised and answered. In part for practical, commercial purposes, he explained, because these Christian dates were critically important for Jews doing business with Christians. But also among Jews themselves. As one medieval English contract written in Hebrew he cited demonstrates, contracts between Jews as well as with Christians bear witness to Jews using the Christian calendar dates to record sales or to date a deed.

But Stern identified a second and more complex explanation. Mockery. In the Hebrew versions of these calendars, Stern detected subtle changes of language from the original Latin formulations to their Hebrew adaptations. For example, a Jewish scribe writing in Hebrew in LJS 57 ignored the more respectful forms of identification of the date of the martyrdom of a given saint or way of describing the Annunciation of Mary. Instead, Stern pointed out Hebrew paraphrases referring to a saint being “killed,” not “martyred,” on a particular day, altering linguistic signs of reverence or theological respect. And in Latin calendars, he similarly showed polemical cartoons deriding Jews and Judaism. These lampoons filled in the blank spaces of the manuscript page for reasons entirely unrelated to the purpose of the calendar. Stern thus called attention to the deeply felt visual and linguistic antagonism and polemics that characterized intercommunal Jewish-Christian relationships.

But the story he tells about LJS 57 is not one of simple binary formulae of opposites and antagonisms. In these colorful celestial maps and calendars, alongside their very technical astronomical tables, is clear evidence of nonpolemical, eminently practical modes of recording data as a basis for intercommunal contact, exchange, and imagination. If the polemics are an adjunct, and indeed not relevant to the main purpose of these works, the science is purposeful, and the art intentional. We witness such intentionality in illustrated animal forms for imagining the position of the stars or in the neutral alphabetical methods of fixing the dates of the days of the week with different colors. We experience it in the black and red visual highlights which help the reader navigate the text. We find utility in the conversion tables that facilitate movement from one calendrical system to another. With understated delight, Stern argued that ostensible binaries like aesthetics and scientific data, inexact celestial maps and precise star catalog illustrations, Judaism and Christianity and their tools for the conversions of time and belief, are bound up together.