Fun a ganef iz shver tsu ganvenen*: On Holocaust Linguistics

Disaster leaves indelible traces on language. How can old words navigate the new and radically discordant? Hannah Pollin-Galay asks that question of several glossaries of Holocaust Yiddish.

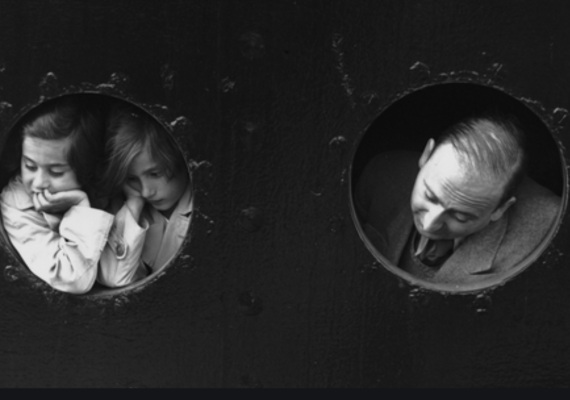

Disaster not only alters the horizon of meaning for those who experience it but also leaves indelible traces on the lexicon. How can old words navigate the new and radically discordant? Language struggles to keep up. Words and expressions are coined or reused and the new collective argot in turn allows previously unimaginable things to become assimilable. Such an absorption of trauma is the topic of Hannah Pollin-Galay’s “‘A Rubric of Pain Words’: Mapping Atrocity with Khurbn Yiddish Glossaries” (JQR 110.1, Winter 2020). In this essay Pollin-Galay examines some of the first linguists to map the evolution of Yiddish in and after the Holocaust. It is a close look not only at what she calls a “catastrophe dialect” but also at the ways postwar scholars tried to make sense of the changes that National Socialism wrought on the language and its vocabularies.

The essay focuses on Yiddish words invented or repurposed through the course of the Second World War that were compiled into glossaries by three scholars active in the aftermath of the war: Nachman Blumental, Elye Spivak, and Israel Kaplan. Through them she seeks to “illuminate the range of ideologies that led people toward Yiddish philology and linguistics as a response to catastrophe” (p. 167). Their interests varied widely, from vernaculars, folklore, linguistics, and social psychology, to language as a lever of political and social change, a backdoor to history, or a telling snapshot of the historical and national Geist of its speakers. Pollin-Galay shows how understanding the changes that the war effected in Yiddish expands and nuances our interpretation of postwar Yiddish literature.

It is a disturbing and riveting project.

Especially trenchant are her case studies of certain clusters of words and semantic fields that emerged during the war years. She looks at the explosion of terms relating to theft, animals, and sex, and their metaphoric expansions. Her three linguists drew attention to these new usages and theorized them in different ways. Pollin-Galay thus moves on two levels, from the suggestive data of the language itself to the ways her scholar/survivors interpreted these phenomena. Is the wealth of words for theft in wartime Yiddish evidence of desperation and privation? Of moral degeneracy and lawlessness? Were they celebratory boasts of Jewish agency in times of scarcity? Traces of an everyday rebellion? The questions are themselves of interest, and how her scholars answer them are revealing as well. Citing Italian linguist Umberto Eco, Pollin-Galay treats these Holocaust glossaries as “maps” or “labyrinths” that “chart […] how knowledge is organized and applied among members of a cultural network, at a given moment in time” (p. 165). Khurbn or Holocaust Yiddish, she says, when seen in through these concentrated lenses, reveals a “verbal subplot” that allows us to read the Yiddish of the war and post-war eras with new eyes.

* It’s difficult to steal from a thief