The Demons inside Ashmedai

One can never hear enough about the ceaselessly enigmatic and compelling tale of Solomon and Ashmedai.

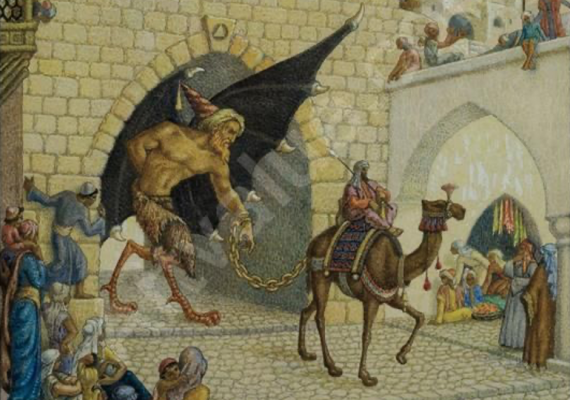

One of the most fascinating tales in the Babylonian Talmud is the story of Solomon and the demon-king Ashmedai (bGittin 68b–69a). The story involves a magic ring, a shape-shifting demon, and the shamir, a magical worm or herb that splits rocks. In his recent article in the Jewish Quarterly Review (111.1), “Solomon and Ashmedai Redux: Redaction Criticism of bGitin 68b,” Reuven Kiperwasser elegantly analyzes the redaction history of the tale, and sheds light on its meaning.

As Kiperwasser shows, the finished talmudic narrative is sewn together from three stories, each of which views the relation of Solomon to the demon in a different light. In the first story, Solomon enlists the help of a demon to build the Temple. In the second, he builds the Temple using the shamir, and needs no demonic aid. In the third story, Solomon is cast into exile by a shape-shifting demon who takes his place on the throne. In the first story, the demon is helpful and presumably friendly or even virtuous, in the last, it is aggressive and presumably wicked; in the middle story, there is no demon. Our redactor has joined the three stories into one.

Kiperwasser correlates the differences between these stories to the differences between conceptions of demons in Byzantine Christian culture and in Iranian culture. In Byzantine hagiographies, demons are the embodiment of wickedness and temptation. By contrast, in Iranian legends, they are neutral or even friendly creatures, very helpful in building palaces. The latter conception stands behind the legend of Solomon building the Temple with demonic aid. But when Christians saw Solomon’s use of demons as intrinsically wicked, Jews responded (Kiperwasser argues convincingly) with a new legend, in which Solomon uses the magical shamir, not demons, to build the Temple. The story in which the demon sends Solomon into exile also emphasizes that the demon-king is Solomon’s enemy, not his ally.

Kiperwasser’s analysis illuminates a puzzling aspect of the talmudic story. In the first part of the tale, the demon is described as a scholar who studies Torah every day in the heavenly academy. All the commentaries work to harmonize this with the end of the story, where it is revealed to the Sanhedrin’s investigators that the demon has been very wicked. But Kiperwasser’s analysis helps us. In the original version of the first story, Ashmedai was a magical helper; why should he not have been a Torah scholar? In the last story, he is lustful and wicked.

There is more to say, however, about our redactor. Each part of the story also has a midrashic history as well as a redactional one. The legend that Solomon was master of demons was confirmed by the exegesis of Ecclesiastes 2.8, while the tale of the shamir developed from the interpretation of 1 Kings 6.7. The notion that Solomon was replaced as king by a demon (as I argued in another essay in JQR, Solomon and Ashmedai (bGittin 68a–b), King Hiram, and Procopius: Exegesis and Folklore) developed from the exegesis of Ezekiel 28.12–14.

But it was surely the redactor himself, whose work Kiperwasser has illuminated so well, who added yet a fourth biblical verse into the mix. This is in yet another section of this rambling tale, and it casts the entire story in a new light. The verse was Proverbs 25.15, "A gentle tongue can break a bone." Stronger than rock, stronger than iron, stronger even than demons—a gentle tongue.