Q&A: Katz Center Fellow Elisabeth Gallas on Jewish Legal Activism and the Nuremberg Trials

Steven Weitzman speaks with fellow Elisabeth Gallas about the New York Black Book of 1946.

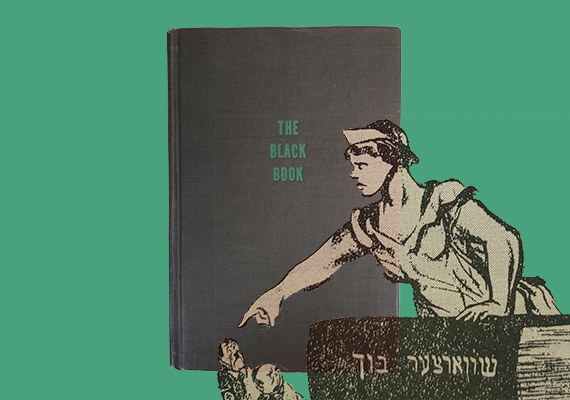

Steven Weitzman (SW): Elisabeth, thank you for contributing so much to our fellowship program this last semester. You came to the Katz Center to do research on something that you refer to as the “New York Black Book of 1946.” Can you tell us a bit about what this text is and what led you to investigate it?

Elisabeth Gallas (EG): The Black Book was published in New York in the spring of 1946 with the goal of providing evidence of the German systematic mass murder of the European Jews. Its publication was the outcome of a unique collaborative effort of a group of Jewish intellectuals and activists from the United States, the Soviet Union, and the Yishuv in Palestine. Given the political reality of the emerging Cold War, this collaboration was somewhat unlikely. Members of the Moscow Jewish Antifascist Committee, the World Jewish Congress, the Va’ad Leumi, and the Committee of American Jewish Writers, Artists, and Scientists worked together on this comprehensive documentary volume.

The volume presented and contextualized manifold sources revealing the different stages and forms of the genocide, including letters and reports of Jewish eyewitnesses, Red Army soldiers, and war reporters, as well as reprints of press reports and perpetrator documents spanning the entire time of the Nazi rule in Europe.

The initiators of this project wanted to confront the English-speaking public with the dimension and new nature of the crimes, which most contemporaries outside Europe could not fathom. This aim to make the Jewish victims’ voices heard was outstanding at the time. But their intentions reached even further: closely following the Allied preparations for a military tribunal to prosecute the Nazi perpetrators in Nuremberg, they envisioned a Jewish bill of indictment, bringing them into active involvement in the proceedings against the Germans.

The explicitly legal dimension of the volume struck me as extraordinary. We know of quite a lot of different initiatives of survivors striving for justice in the aftermath of World War II, but this form is different on many levels. The Black Book’s transnational character, its authors’ claim to represent the entire Jewish collective in its will to try the Nazi crimes, and its quasi-legal format make this volume a highly interesting and specific example of postwar Jewish legal activism in response to the Holocaust.

(SW): This early effort to find justice for the victims of the Holocaust is very moving and seems to show faith in the possibility of justice. I wonder if this possibility felt realistic at the time. What did those who produced this text hope to achieve in a practical sense? In retrospect, their efforts feel quixotic, but did they have any chance of success?

(EG): This is a complex question because it needs to be addressed from different vantage points. First of all, the Black Book project is an expression of the general urge to act felt by Jewish contemporaries of the catastrophe. Such commitments were driven by a strong sense of duty toward the murdered and their memory.

The idea to create a Black Book was also building on a long (especially Eastern European) Jewish tradition of collecting, preserving, and presenting evidence of experiences of anti-Jewish violence in Europe. For decades, there had been political efforts to create public awareness of injustice through publishing reports and documentary volumes. Still, the New York Black Book has many unique features, especially in its format and presentation. It was certainly not meant for a Jewish audience, and it was also not created solely to inform and win over the general public for the Jewish cause. It was clearly meant as an intervention into Allied jurisdiction. This astonishingly sovereign move must be seen in the context of the World Jewish Congress’s activity in postwar retributive and restorative justice measures.

These efforts to participate in the prosecution of Nazi perpetrators failed to a large extent, and so did the idea of the Black Book. But other Jewish initiatives in the realm of restitution and indemnification were more successful, so we cannot dismiss the whole approach as illusionary and unrealistic. The Black Book was not able to achieve direct participation of the Jews in postwar trials against the Nazis or their collaborators, but I sense that many of the documents collected for it made their way into the hands of the Allied prosecution teams in Nuremberg and helped them to gain a more nuanced picture of the crimes.

(SW): I know your research on this text is ongoing, but can you give us some brief sense of what you were able to learn about this Black Book while you were at the Katz Center?

(EG): I learned much more than I could have hoped for—and this was mainly due to the incredibly rich archival material I was lucky enough to find and access at the Katz Center’s library. The Library holds the papers of the indisputable protagonist of the American version of the Black Book, the Russian-born Ben Zion Goldberg (there was also a Russian version of the Black Book planned at the same time by the Jewish Antifascist Committee, but it fell prey to Stalin’s censorship.) In the 1940s, Goldberg was a well-known and established Yiddish publicist in New York with a strong dedication to the Jews in the Soviet Union. He headed the Writer’s Committee, a group of Jewish intellectuals devoted to supporting the Soviet war effort against Germany and to raising awareness of Nazi crimes.

Goldberg’s estate was a treasure trove for me, including many letters and reports directly related to the Black Book’s committee and its work. I am indebted to Arthur Kiron and Bruce Nielsen, who helped me navigate this large estate, especially the uncatalogued parts. The material preserved by the Library at the Katz Center enabled me to better understand the challenges, visions, motifs, and contexts of this operation. Last but not least, I gained tremendous insight from the other fellows, whose comments and suggestions helped me to think outside the narrow box of postwar Jewish history and to understand this Black Book better.

(SW): I know this is part of a much larger project. Can you tell us about that project and how this study fits in?

(EG): The story of the New York Black Book—framed as a Jewish bill of indictment for the Nuremberg Trials—will form a chapter of my larger study, in which I focus on Jewish forms of indictment in nineteenth- and twentieth-century Europe. This project centers around Jewish legal or quasilegal responses to libel, discrimination, and violent atrocities in modern European Jewish history. I am especially interested in the way the legal sphere is addressed and legal instruments are used by European Jews to counter attacks and respond to discrimination and violence.

This history of responses to atrocities is marked by a transition that seems crucial: a development that can be described as a movement from lamentations directed inward toward the Jewish community and the divine, to outward-directed accusations against perpetrators. I try to reconstruct a process of juridification of the tools used in reaction to ritual murder, exclusion, pogroms, and all different forms of violence the Jews experienced.

A background to this story is that international (criminal) law offered no tribunals where Jews as a nonstate collective or minority could bring their victims. I want to show in my study that there were manifold attempts to confront that problem, and to detach Jews from a position of passive dependence by using many different formats to publicly and legally indict wrongs inflicted on them. Documentary books were one expressive means, as mentioned, with a longstanding tradition to create and publicly present evidence of crimes; the Black Book is a notable example.

(SW): I’d like to ask you about another very important aspect of your work: As deputy to the director of the Leibniz Institute for Jewish History and Culture–Simon Dubnow, you are part of the leadership team of a preeminent center for Jewish studies research in Europe. I won't ask you to summarize everything the center does, but since you head its research unit dedicated to law, can you give us a glimpse of what questions are being pursued there, and how they might relate or be different from the questions we have been exploring this year at the Katz Center?

(EG): In general, the Institute in Leipzig follows the historiographical tradition of its namesake Simon Dubnow—one of the most important Jewish historians in modern times, advocate and representative of a secular historiography, and cultural mediator between Eastern and Western European Jewry. In the research unit “Law” of the Dubnow Institute, we focus on the modern (at the moment, mostly nineteenth- and twentieth-century) Jewish experience in central and eastern Europe, and in the centers of Jewish migration. Our research resonates with what we discussed as Katz Center fellows, although our approach is less multidisciplinary as we take a primarily historical perspective. Specifically, we explore questions of legal standing and status, citizenship, and the establishment of minority protection systems.

The members of the Law unit in Leipzig mostly deal with Jewish emancipation history and its rupture in the twentieth century, highlighting negotiations of Jewish recognition, belonging, participation, and self-understanding in the age of the modern nation state. We look at the ways in which Jews were involved in the shaping of various areas of law, especially international, public, and criminal law in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Committed to a cultural-historical approach, we also profile an area in which questions of restitution, heritage, and provenance are especially relevant.

One field we explored as fellows this year is traditional Jewish law and halakhah. These topics are especially relevant at the Institute in Leipzig when projects touch upon the tensions between state law and religious law and the manifold debates regarding their relationship in central Europe. I learned a lot in this regard (and much more) from the fellows at the Katz Center.