Point/Counterpoint: Jewish Activism in 1944 and the Bombing of Auschwitz

In this JQR forum, two scholars debate how fateful decisions were made.

In volume 111.2 of JQR, historian Zohar Segev wrote an article, “Rethinking the Dilemma of Bombing Auschwitz: Support, Opposition, and Reservation,” that relied on new archival documents to argue that World Jewish Congress official Leon Kubowitzki lobbied U.S. administration officials to consider a ground assault on the Auschwitz extermination camp. Kubowitzki, according to Segev, managed to gain the ear of administration officials such as Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy, who contemplated means of disabling Auschwitz other than aerial bombing.

Segev’s article, with its account of a new approach promoted by Kubowitzki, prompted a rejoinder from Rafael Medoff, who insisted that the Americans were uniformly opposed to deploying military resources to disrupt operations at Auschwitz. In the name of open scholarly exchange, we present in this online forum Dr. Medoff’s objections, followed by Professor Segev’s response to him.

—The editors

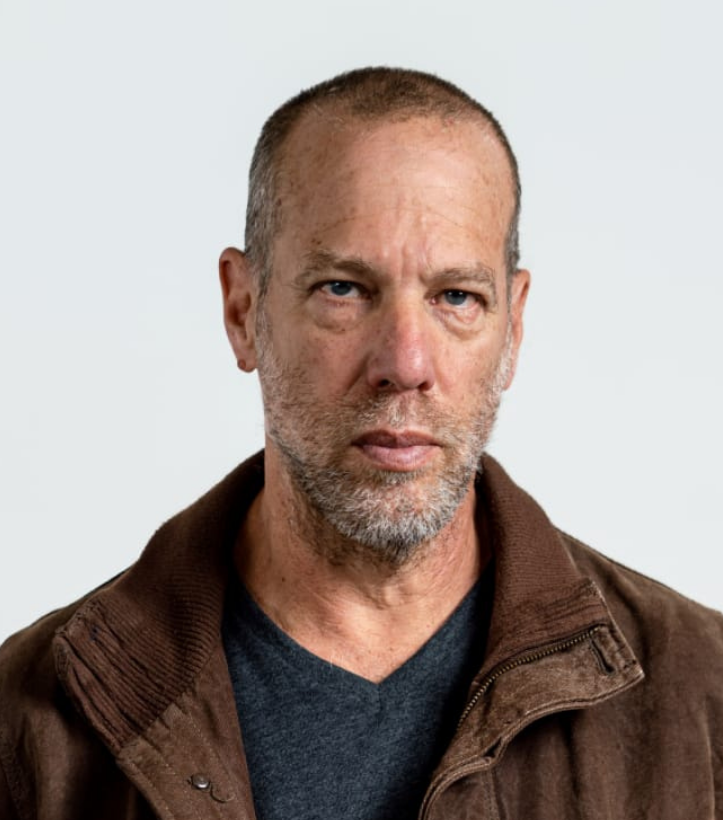

Rafael Medoff

The Roosevelt administration’s rejections of requests to bomb Auschwitz, or the railways and bridges leading to it, were based on a policy decision to refrain from using military resources “for rescuing victims of enemy oppression.”

That decision was made by senior War Department officials in February 1944, four months before the first Jewish request for such bombing. Contrary to Zohar Segev’s argument in his JQR essay, there is no evidence the administration’s decision was influenced by the fact that one official of one Jewish organization opposed air strikes on the camp.

As hundreds of thousands of Hungarian Jews were deported to Auschwitz in the late spring and summer of 1944, at least thirty officials of Jewish organizations or publications urged the Allies to bomb the railways and bridges over which the deportation trains traveled, or to bomb the gas chambers themselves. Nahum Goldmann, cochairman of the World Jewish Congress, met with American, British, and Soviet officials to promote both of those bombing proposals.

One of Goldmann’s subordinates, A. Leon Kubowitzki, chairman of the group’s rescue division, agreed with the idea of bombing the railways, but also thought any attack on the camp itself should be done by ground forces rather than air strikes, fearing bombs could hit inmates. Prof. Segev claims (p. 288) that Kubowitzki’s position “contributed to the crystallization of the opposition within the U.S. administration to bombing the camp.” But the timeline of the events in question contradicts his claim.

On June 26, 1944, in response to the first bombing request, War Department officials composed an internal memo spelling out their rejectionist position, based on the February policy decision. Echoing that memo, Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy rebuffed the bombing request on the grounds that an air attack on those railways was “impracticable” because it required “diversion of considerable air support essential to the success of our forces now engaged in decisive operations.” McCloy used the same language to reject subsequent bombing requests.

In truth, no “diversion” was necessary because during that same period, American bombers repeatedly struck German oil factories located in the Auschwitz industrial zone, a few miles from the gas chambers. They also bombed railways and bridges throughout Europe—but not the ones leading to Auschwitz.

Here is where the timeline is crucial. The War Department’s policy memo was dated June 26, 1944. But A. Leon Kubowitzki’s first letter to U.S. officials urging ground troops instead of bombing, was dated July 1, 1944; he may have also said it verbally to a U.S. official on June 28. Either way, Kubowitzki communicated his position after the War Department had already articulated its rejection of the bombing requests.

There is additional evidence that Kubowitzki’s concern about harming inmates did not influence U.S. officials: they bombed the Auschwitz oil factories in broad daylight, when slave laborers were likely to be present. Indeed, some of them were killed or injured. The U.S. also bombed the V-2 rocket factory at Buchenwald in broad daylight, killing several hundred inmates. The presence of civilians at both targets did not deter the U.S. from attacking.

The opinions of American Jewish officials had no impact on the Roosevelt administration’s policy. There are no documents showing that either the thirty Jewish officials who urged bombing, or the one Jewish official who opposed striking the gas chambers from the air, influenced the U.S. position. The Roosevelt administration had decided it would not bomb Auschwitz or the railways and bridges, and it never wavered from that tragic decision.

Rafael Medoff is founding director of the David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies.

Zohar Segev

On October 17, 1944, during a joint meeting of the Advisory Council on European Jewish Affairs and the European Representative Committee, Leon Kubowitzki, chairman of the Rescue Committee of the World Jewish Congress, reported on the endeavor to undertake an attack on Auschwitz. At the end of his report, Kubowitzki said, “We have said to all whom it might concern: History will never understand that there have been death factories organized to kill human beings at a speedy pace, and that nothing was done to destroy these installations, so as to slow down at least the pace of the slaughter. We have asked that the installation be attacked in force either by the Polish underground or by Soviet paratroopers or, if possible, by allied paratroopers.”

The minutes show the absolute awareness by Kubowitzki of the dramatic murder process that was taking place in Auschwitz every day and reflect the issues I aimed to raise in my JQR article.

The Auschwitz concentration and extermination camp lay within the range of Allied bombers; this fact led to demands to bomb the camp. Of course, my article mentions that there were calls to bomb Auschwitz; it also refers to the important contributions of Prof. Wyman and Dr. Medoff to research on this subject. My purpose was to shed light on a different approach taken by a number of Jewish rescue activists in the U.S. regarding the bombing of Auschwitz. The documents presented in my article demonstrate that during 1944, Kubowitzki, as the chairman of the Rescue Committee of the WJC, focused his efforts primarily on a ground operation against the extermination apparatus in Poland and the rail lines leading to it. This was a significant strategic move whose audience was the U.S. administration, the Allies, and governments in exile, and was also communicated to the Zionist leadership in Palestine.

Kubowitzki played a leading role in the rescue efforts directed by U.S. Jewish organizations, and led the charge in advancing the idea of a ground operation against Auschwitz in official meetings and committees of the WJC. My article aims to show that opposition to the bombing of Auschwitz from the air was not the only direction of activity taken by the American Jewish leadership in 1944. From the diverse sources presented in the article, it can be clearly seen that the option of a ground attack on Auschwitz has not received the proper place in research.

Dr. Medoff raises a question about mistaken chronology. In the article I discussed this issue carefully and wrote: “It is difficult to determine to what extent the opposition of the WJC to the bombing of Auschwitz from the air affected the fact of not bombing the camp” (p. 288). The documents presented in the article indicate that Kubowitzki believed the administration’s policy regarding the bombing of the camp could have been influenced. We also learn this from the response of the Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy (August 30) to Kubowitzki’s request to use special forces against the extermination camp. Based on this response, the reader is left with the clear impression that the issue of how to disable Auschwitz was still under consideration.

Moreover, it seems mistaken to argue that in the dynamic and chaotic reality of a global war, decisions made four months earlier could not be changed. Policy deliberations were ongoing and shifting in the rapidly changing reality of the day: the situation in Hungary, the advance of the Allies, information about developments within Nazi Germany, etc. Moreover, my claim that WJC leadership could influence the activities of the American administration should be understood against the backdrop of the intensive and significant network of ties that WJC leaders maintained with the American administration during World War II, as I presented in the introductory part of the article.

Zohar Segev is a professor of Jewish history at the University of Haifa.

Caption:

“Lessing and Lavater as guests in the home of Moses Mendelssohn,” by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim (Judah L. Magnes Museum), source WikiCommons.