Outside In: Fellows Write from and about Home

A virtual round table on our changing domestic worlds among fellows from the Katz Center's year on the Jewish Home.

The Katz Center fellowship is a residential one, meaning that its central aim is to bring people together to work physically side by side for extended periods, with fellows making temporary homes in Philadelphia. With the arrival of COVID-19, this defining feature of our collective work has disappeared. Instead, under orders to shelter in place, our homes are capturing our attention in new ways. Home’s boundaries, contents, and location, its material and emotional culture, are, for the moment at least, our whole worlds.

As it happens, the home has also been the focus of the fellowship theme this year, with fellows sharing research about the history and concept of the home in diverse Jewish contexts and cultures, so they’re well positioned to take the long view. I spoke with a few of them to think together about how the loss of a shared physical space and the transformation of our separate household spaces into virtually shared ones relates to their work—intellectually, professionally, and personally.

Anne Albert: Nathanael, you mentioned to me that your current home is quite temporary, a situation that has become normal for you. Say more?

Nathanael Riemer: Yes, if you would ask me personally, I would have to answer that I don't have a real "home." I moved out of my parents' house when I was 18 years old, so it is not my home. To my neighbors I am a stranger; my house in Philadelphia is not my home, even though my landlord has already become a real friend. My apartment in Berlin is rented for a limited period of time—just like all my jobs in the past were limited. I don't know if it is worthwhile for me to build something like a home in an extremely changing world. At some point you have to leave home anyway.

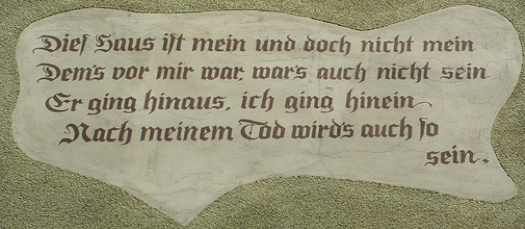

It is interesting that one of the most famous (non-Jewish) house inscriptions articulates this:

“This house is mine and yet not mine / He who was before me also thought it was his / He went out, I went in / After I die, it will be the same.”

AA: This notion of home as transient and unstable conflicts with the sense ingrained in our culture that home is a place to which you will always return, a place with a sense of permanence—and likewise, a place of deeply personal, even unique connection.

But, of course, you are not the only one experiencing such a contradiction. As we know, large groups across the world—from college students to migrant workers—are similarly dislodged. Keren, your work might speak to the way notions of home and identity are playing out on a national scale.

Keren Friedman-Peleg: Right now, our private, intimate home has come to be the main answer to this overwhelming, global crisis; staying at home (and away from those who are not our close family members) is the single most important action we can take to fight this pandemic.

Our political leaders, official authorities, and medical experts—all of them are pushing us back to the place they usually encourage us to leave; the main message is to stay rather than to move, to be rather than to do, to be more passive and less active; to focus on the personal/ domestic/ local levels, rather than on the global/ public/ professional levels.

Seeing from this perspective, now is in many ways the "golden hour" of the home, or the comeback of the private—an act (to stay at home) that sometimes presented as an indication of vulnerability (to stay at home as a sign of avoidance, of fear and even depression) has now become an expression of resilience, some kind of 'heroic act', a new virtue…

Suddenly, the most private, physical and emotional, space, has been “nationalized” as the "front line"...

So, how might this switch of meanings shape the ways we experience and think about our home and about homes of others? About the national home versus the private home? And even about globalization, a process sometimes associated with phrases such as "home is everywhere" and "home is where the heart is" (clearly, not the right messages in combating this crisis)? And, what happens to all the local, culture-oriented, idiosyncratic features of home (as in the “Jewish Home”), when home has come to serve, so to speak, as weapon in fighting a global pandemic?

AA: On the other hand, in some political contexts, notably on the right in the US, there is also a view that it is in the national interest not to stay at home, but rather to maintain industry and economy even at great risk. We should also acknowledge that the pressure to put oneself at risk outside the home is unequal, affecting poorer workers like grocery clerks, delivery people, and sanitation workers disproportionately—not to mention health care workers who are most endangered.

It strikes me that this opposition between the national home and the private home, or between home and work, leaves out another kind of home, which is the working home. In fact, we’ve seen in various ways this year that the home as a place specifically walled off from work, designated as a respite, is a particularly modern conceit.

Gregg Gardner: Definitely. Regarding the household in Jewish antiquity, workspaces were often connected to—or completely integrated within—the architecture of the household. This includes rooms used as workshops for ceramic production (lamps, in my work) and spaces appended to a home that open to the street and serve as storefronts. We know this not only from archaeological finds, but also literary sources, such as ancient rabbinic texts (Mishnah, etc.). Here, we even see some of the social and familial consequences of “working from home,” so to speak. One rabbinic text, for example, addresses complaints about noise from small-scale manufacturing work carried out in a courtyard that was shared by multiple households. While the rabbis are generally keen to place limits on noise in shared spaces, especially after dark, they urge tolerance for those who need to work in these common spaces. It's perhaps a reminder of how one's home life, and how they treat extensions of their home, can impact the lives of others.

AA: As I’m typing this, I’m simultaneously helping one of my kids connect to his temporary online “classroom.” It’s easy to imagine that talmudic-era mothers and fathers were similarly pulled in many directions—though perhaps without the disconnect created by a need to maintain the appearance of professionalism, which almost by definition excludes family and other dimensions of household life.

Vanessa Ochs: That disjunction is increasingly breaking down. Anne, when you invited us to participate in this conversation, I was starting to think about what "backdrop" in my home my students would see when we have a zoom seminar this afternoon. Most of my students will be zooming in from their bedrooms … so as we are less intimate, we are more so.

AA: Joshua, you’ve been working on Jewish experiences during outbreaks of plague in the early modern period, how do they compare?

Joshua Teplitsky: Certainly, the outbreak of an epidemic often confounded the cherished (though perhaps imaginary) boundaries between home and the outside world. When plague ravaged the city of Prague in 1713, some of the very first guidelines issued by Habsburg imperial authorities were instructions for the cleaning (Reinig- und-Sauberung) of houses and the separation of Christian and Jewish laundry-women from each other.

AA: Rather than work life, you’re pointing to the way government regulations encroached on the supposedly private sphere. Our homes are “public” now in the sense of being visible, but also in the sense of being part of a larger civic and cultural body, as Keren also pointed out.

JT: Yes. In our own time, the boons of technology have permitted the fortunate to maintain their jobs and education, albeit with significant challenges, “from home” by using media tools. But this, too, comes as a form of intervention and encroachment. Working at home means allowing our colleagues a glimpse into the domain that we usually expect to offer a refuge from the spaces of work (even if that expectation is honored more in the breach during normal times as well). The public health response—coupled with the technological revolution and cultural shifts toward broadcasting private lives—signals, at least for a time, that a domestic space safely ensconced from the public sphere is now more than ever an illusion: certainly not a reality, perhaps no longer an ideal.

AA: This can be seen as an intrusion and also as a transformation of the experience of home. It’s also transforming our collectivities, isn’t it? Homes are also increasingly part of collective religious observance, as people are sharing seders, bar and bat mitzvahs, and Torah services from their homes over Zoom, eroding the difference between individual and communal ritual.

VO: This past Shabbat, before it started technically, all of my cousins and aunts and uncles across the country, representing most of the "flavors" of Judaism, joined (from our homes) to sing and hear some words of Torah. It included people who would not eat in some of the other households, where the kashrut standards do not match their own. This way the boundaries of what counts as a Jewish household can become more porous, even as we are closed off literally.

AA: So it also softens walls between denominations in a way that is specific to Jewish experience. We’ve come all the way from Nathanael’s comment on universal recognition of the transience of life to a very particular Jewish dimension of the way homes define us.