Pandemic and Plague: Echoes from the Jewish Past

In this JQR blog forum, scholars reflect on past Jewish experiences of plague, pandemic, and quarantine.

In our own attempt to make sense of the radically altered world we now inhabit and to provide intellectual stimulation to our readers, the editors of JQR asked four prominent scholars to reflect on what historical and literary resonances the COVID-19 pandemic prompted in them. The forum below offers concise responses that move in time from the Black Death in the fourteenth century to Israel in the twentieth. They offer insight into what we can learn from and compare to the past, as well as how we should recognize that which is different in the past from our own times.

In this extraordinary time, JQR will be here to offer a space for serious reflection on the past and present.

The Editors of JQR

Comparing Pandemics

Susan L. Einbinder

Professor of Hebrew and Judaic Studies and Comparative Literature at the University of Connecticut, Storrs

The Black Death launched the Second Plague Pandemic, with continuing outbreaks over the next half-millennium. By the fifteenth century, medical experts saw that plague was increasingly indiscriminate, though they could not understand why. Then as now, pandemic—whether bubonic plague or a coronavirus—tested the limits of how medical people understood disease, what caused it, and what might stop it. Then, as now, certain populations proved more vulnerable, and early plague responses encouraged public policies targeting the poor and subjecting them to greater surveillance. Confined populations like the ghettos posed other challenges, as seen also today in nursing homes, cruise ships, prisons, and refugee camps. Although Jewish historians have tended to focus on episodes of anti-Jewish violence, such violence was not universal in 1348 and was rare during subsequent outbreaks; scapegoating tended to target other marginal populations: the poor, foreigners, sometimes physicians. Each outbreak has its own context and its own dynamic, and comparisons should be made with caution.

The question for historians is how we compare past and present events. In some general ways, comparing coronavirus and plague is helpful. Many nonbiological similarities are striking—the prayers, miracle cures and prophylactics, isolation measures, administrative turf wars, resource disparities, academic debates, the strain on families, institutions, and economy. Plague, like newer zoonotics, is also a consequence of environmental and multispecies disruptions, whose carriers emerge from ecosystems we humans have disturbed. On the other hand, plague and coronavirus are very different diseases. Bubonic plague is not contagious. The bacterium yersinia pestis is transmitted by flea and now treated with antibiotics. In contrast, COVID-19 is an extremely contagious virus, of uncertain incubation and no known immunity. COVID-19 and bubonic plague are thus distinctive diagnoses. At the same time, their biological differences are not always reflected in the social realm.

The same holds true for their aftermath. In 1631, when the plague ended in Padua, sixty percent of the ghetto was dead. Wearily, the physician Abraham Catalano wrote that life resumed in “a world upside-down”—a world we haven’t reached for comparison yet.

A Pinkas in a Plague Year

Joshua Teplitsky

Assistant Professor of History at Stony Brook University

What could be more surreal than writing a book about Jews and plague in the middle of a global pandemic? For the past two years I have been collecting materials to write a microhistory of an outbreak of the plague in Prague in 1713 and to reconstruct the quotidian, communal, and cultural aspects of this final occurrence of the disease as it impacted Jewish life in this early modern city. The plague claimed the lives of between a quarter and a third of the city’s inhabitants but was also the last of its kind there. It inspired new imperial public health measures, Jewish collective action, rabbinic responsa, and Yiddish memorialization.

My project suddenly feels like a “ripped from the headlines” story with fresh urgency and new meaning. Where I had once conceived of a project that would explore questions of public health responses to the contagion alongside social encounters and material consequences, I am more attuned than ever to the emotional foreboding that precedes the crest of an epidemic. That state, often obscured by later events, might be best described as dread, a sense of the impending, a waiting for the worst to come.

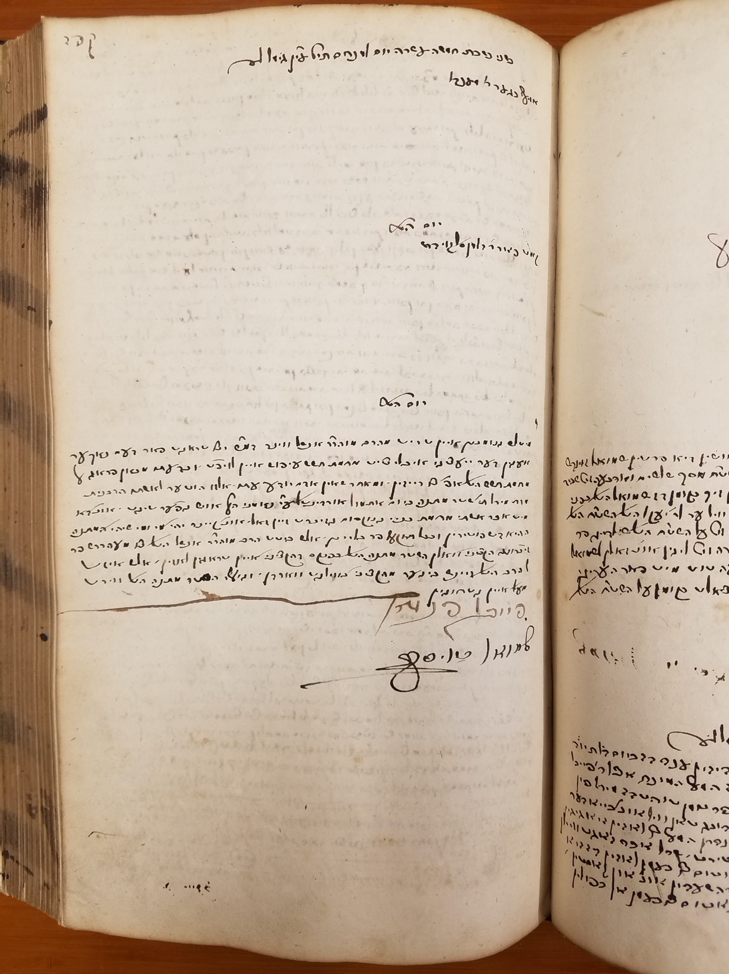

I see these emotions more acutely now when I read an entry in a pinkas from Prague which captures the seemingly mundane contractual arrangements made by Anshel Wiener in the city of Prague on Monday, August 7, 1713, some two weeks after the first reports of illness. Anshel was not a native of the city. He had left his home elsewhere “out of fear of the pestilence,” and intended to continue his journey onward now that the plague had reared its head in Prague as well. In the midst of his flight, with the future uncertain, Anshel availed himself of the standing Jewish court in Prague to make provisions for his family. Citing the passage from Kohelet with foreboding, “for man cannot know his time” (9:12), Anshel arranged for the transfer of his property to his wife, Mirel.

The entry says very little, but one can imagine the mix of emotions Anshel must have had in this moment: fear and flight, resignation and preparation, perhaps hopes of survival. Like those who stockpile food and supplies now, Anshel was facing the dread of the unknown, aware that the future held potentially grim outcomes. His presence in the pinkas shows—something I see more clearly now than before—that even swifter than the movement of contagion or panicked responses to symptoms is the advance dread of the danger to come that had not yet fully arrived. His story reveals the weight of waiting and the power of emotions in world-historical events. In such times, like Anshel in making his legal preparations we think of our loved ones and imagine what we can do to improve their lives, to maintain normalcy even in the face of so much uncertainty.

The Wandering Jew as a Carrier of Disease

Galit Hasan-Rokem

The Max and Margarethe Grunwald Professor emerita of Folklore at the Mandel Institute of Jewish Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

The sin of the Wandering Jews in the medieval and early modern narratives on this figure is projected to the distant past: when Jesus walked to the crucifixion carrying the heavy cross, he asked to rest on the wall of a Jerusalemite, who refused to let him do so. Jesus then cursed him to eternal wandering. As Jonathan Skolnik and Tuvia Singer have shown, new images of the Wandering Jew developed in the nineteenth century in various discourses such as philosophy, politics, religion, art, music and literature that moved the Jew’s sin to the present. Possibly the most famous Wandering Jew of the century is a marginal figure in Eugene Sue’s novel Le Juif Errant (1844), which was originally serialized in a Parisian magazine, and later became immensely popular worldwide. The bad guys of the novel are not Jews but rather Jesuits. But the Wandering Jew, who appears mainly at the beginning and the end of the novel, embodies disease. Wherever in the world he appears, a cholera epidemic erupts. It is however the evil Jesuit, Rodin, who uses the disease in his attempts to gain power and wealth. The Jew as a carrier of disease probably echoes the medieval prejudice associating Jews with the plague. More fatally, this notion is brought into the most antisemitic of Nazi movies, Der Ewige Jude (The Eternal Jew, 1944, dir. F. Hippler), where a procession of vile rats—also traditionally seen as carriers of the plague—represent the unbounded distribution of Jews around the world.

Galit Hasan-Rokem is the Max and Margarethe Grunwald Professor emerita of folklore at the Mandel Institute of Jewish Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Lessons from the Recent Past

Rhona Seidelman

Schusterman Chair of Israel Studies at the University of Oklahoma.

Ultimately, what it comes down to is whether our work as historians matters. I have been studying the history of quarantine for longer than I care to remember. Early in my Ph.D. at Ben Gurion University I was drawn to the subject of the quarantining of immigrants to Israel. I felt then—as I still feel now, many years later—that I had come across one of the most fascinating subjects possible. Studying quarantine has given me an amazing window into Israeli history while helping me consider some of the most fundamental questions about society, fear, exclusion, welcoming and care. But now, in this most critical moment of quarantine history, what does this matter? Mostly, these days, because I am scared, overwhelmed, vulnerable and uncertain, I feel like it does not matter. But then I remember, I am buoyed and I truly believe: it most certainly does. If I were to distill the most important lessons I have taught my students over the years that can help them—us—in this moment, there are two. One lesson is from the history of public health: when implemented carefully, quarantine can work. One lesson is from Jewish history: in uncertain times, watch out to make sure our most vulnerable communities are not unfairly targeted and excluded. I know this from carefully studying history. And knowing this matters.