Medieval Frenemies: Jewish and Christian Martyrs Had a Lot in Common

"Do not be saddened or troubled, good sister. Your brother will die today as a good Jew." These are the words reportedly spoken by a fourteenth-century mendicant friar, just before taking his own life.

"Do not be saddened or troubled, good sister. Your brother will die today as a good Jew." These are the words reportedly spoken by a fourteenth-century mendicant friar, just before taking his own life. He had declared his conversion to Judaism, and despite his sister’s tearful entreaties, he chose a public and violent death over forcible return to his order. One Avraham ben Avraham Avinu, whose dramatic and literally iconoclastic antics made him the subject of at least three contemporary reports, did the same. These acts are the focus of Paola Tartakoff’s essay “Martyrdom, Conversion, and Shared Cultural Repertoires in Late Medieval Europe,” which appeared in JQR 109.4 (fall 2019).

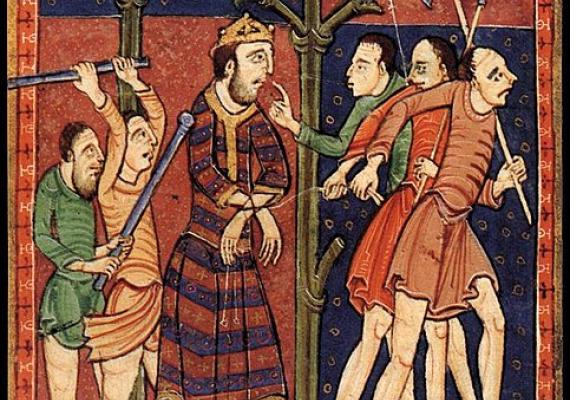

Showy willing deaths like these were not exclusively carried out by those with Christian origins. Famously, some Jews of the era also chose martyrdom, refusing to submit to Christian mobs bent on conversion in the time of the crusades, not only accepting death but actively taking their own lives and the lives of others. (See, for example, Soloveitchik in our pages.) Nor, for that matter, were they limited to Ashkenazi Jews, as some have argued. Rather, Jews and Christians across Europe in the Middle Ages shared in common certain symbols and tropes which they adapted and deployed perhaps as guides to their dramatic enactments of conversion-related martyrdom, but certainly for the form of its retelling. Public declamations, sometimes in holy spaces, purification by water and fire, symbolic violence, and reversal of earlier conversions are just a few of the tropes and symbols that were widely deployed, part of what Tartakoff calls, following Itamar Even-Zohar, a shared “cultural repertoire.”

Applying an approach focused on sharing to sources so intent on self-differentiation, even to the point of violence and self-destruction, is not without irony. One might say that it’s an extreme example of the narcissism of small differences—that with so much in common, distinguishing details matter inordinately. But the context of conversion complicates that conclusion: the majority of the examples Tartakoff brings are ones in which an individual has moved across confessional lines, sometimes more than once, and the commonality they display reflects the fact that conversion is especially conducive to sharing—the convert him or herself the prime cultural intermediary. The symbols, emotions, and ideas of a convert are constructed by the faiths of origin and destination alike. Indeed, conversion is uniquely capable of revealing what is held in common between contexts. These converts (or refusers of conversion) expressed a sense that conversion was a dramatic alteration, and it was felt as a visceral tear in their personal and social fabric. Not only did the sense of drama cross boundaries, but so did the particular religious and emotional language used to describe it.