Demonesses All Around

Amulets for warding off demons become portals to meditations on women and history in two new (free) essays by Avigail Manekin-Bamberger and Andrea Gondos

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Detail: Lady Lilith, 1867, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Women are real. At least so women think, most of the time, but more than other human people women are also imaginary creatures—figments—constructed by cultural and linguistic fantasy, myth and literature. All this we know, as women, as readers of texts, and viewers of art, and consumers of culture in nearly all its forms, and it is no less of a factor in scholarship. It is not always easy to tell the dancer from the dance.

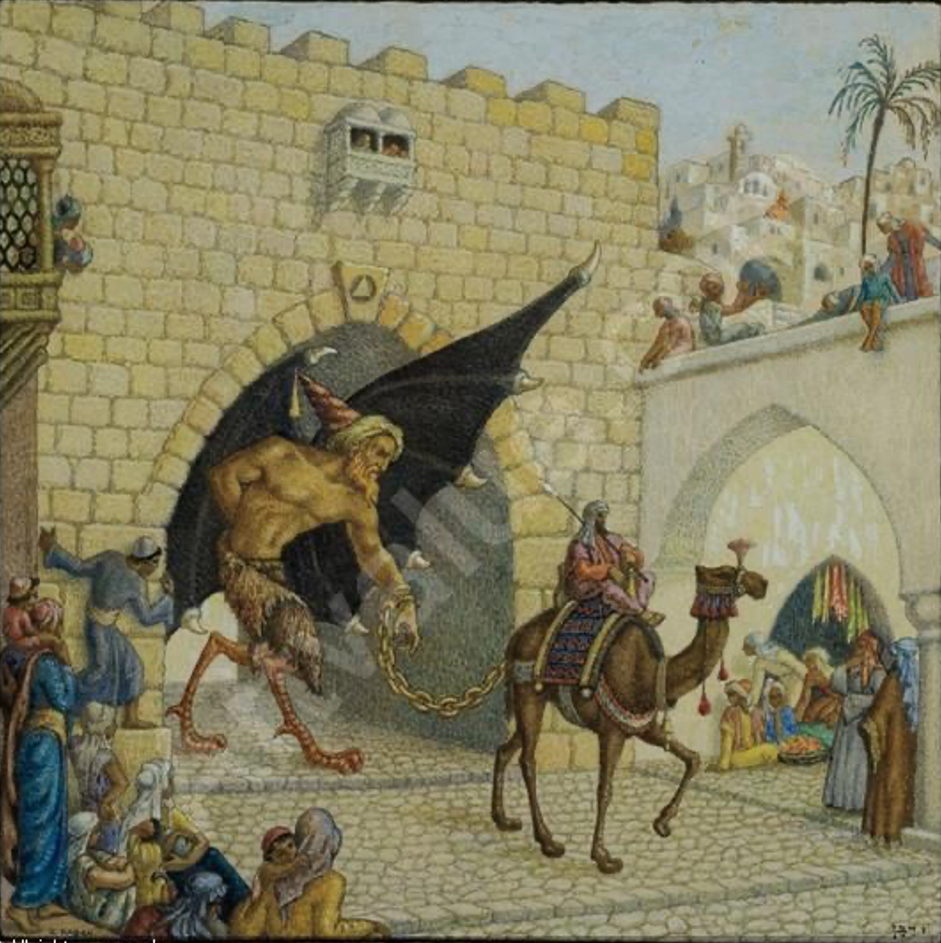

March 2025, Women’s History Month, coincides with the publication of JQR 115.1, an issue that just happens to include two strong essays on women. It is not merely coincidence, however, that many of these “women” are demons, being as they are a particularly pervasive manifestation of the female imaginary. Female Jewish demons, liliths, some with wild hair and exposed genitalia, others donning priest costumes, share in common the threat of chaos to Jewish continuity; one’s work is to dominate them. They remain a potent reality in many forms of premodern Jewish life from Antiquity well into the eighteenth century.

In two essays in this volume (both free to access until May 25), Magic Formulae and Women’s History: Authorship, Agency and Gender in the Aramaic Incantation Bowls, by Avigail Manekin-Bamberger, and The Female Body and the Male Gaze: Magic, Kabbalah, and Medicine in Early Modern East-Central Europe, by Andrea Gondos, the authors look at the cultures surrounding Jewish practices for controlling demons and demonesses. Despite the thinness of the veil between the real and the discursive, each scholars in her way attempts to move through these figures out toward women in the world. This is a fraught project, yet the exaggerated mythical element of the lilith-woman helps both to highlight the more subtle mediatedness of the real-woman, and the space between the real and the imagined is the site of history.

Contrast these demons with the actual human women highlighted in David Ruderman and Alberto Palladini’s essays in our last issue (114.4, Fall 2024). Palladini brings us new documents written by and for the storied grande dame of sixteenth-century Mediterranean business affairs, Doña Gracia Nasi, accentuating her sway over powerful male figures. Ruderman highlights a different kind of female power through a look at two well-to-do English Christian women who befriended a Polish Jewish immigrant to take advantage of his Hebraic learning in the eighteenth century. Palladini and Ruderman depict the complicated dynamics of two real women who interacted in the world using brains, money, social standing, and feminine wiles to (try to) get things done.

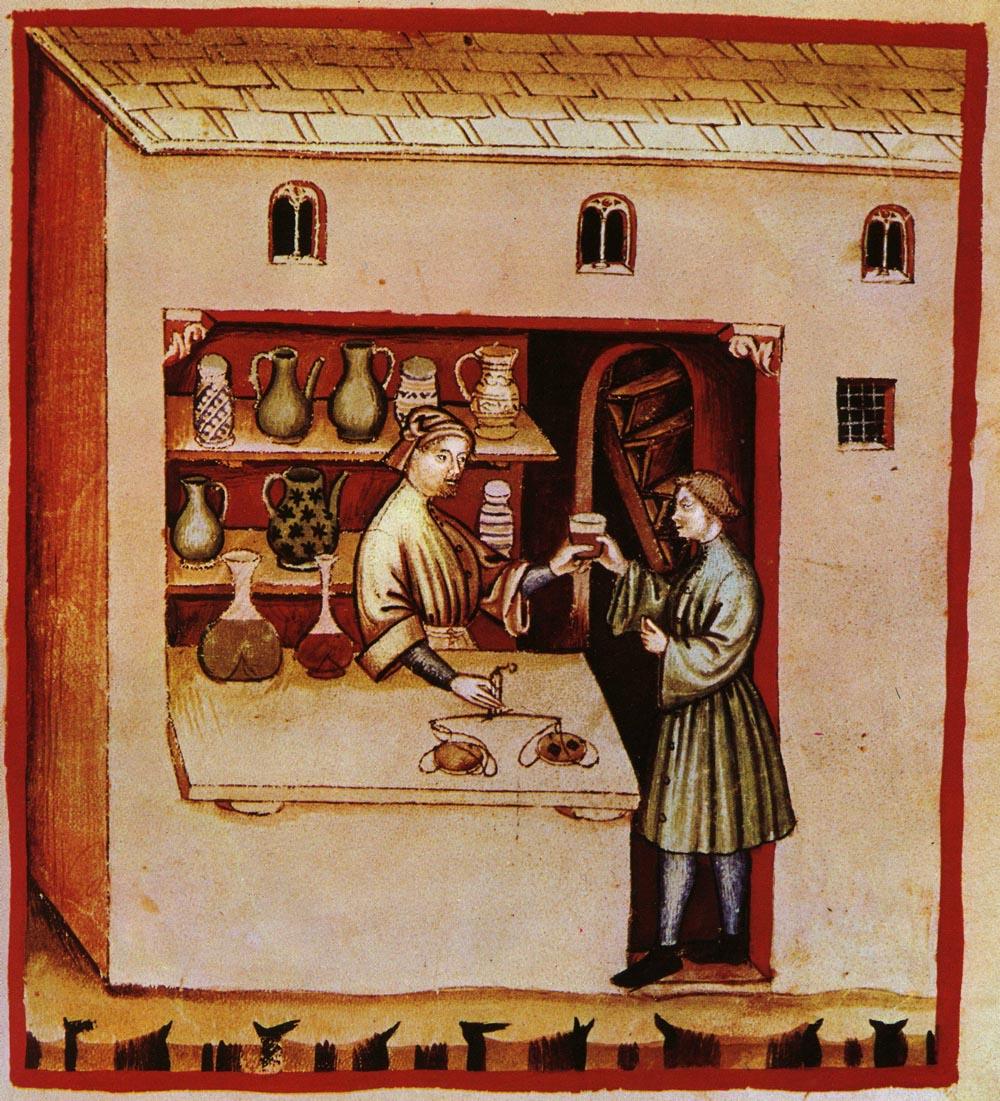

On the other hand, maybe the lilith essays are not so removed from women’s lives. Demon talk is inevitably amulet talk, and amulet talk is always expert talk happening at the edge of religion and medicine. Just as the effective amulet draws the demon out of the possessed, so demon talk draws out a cocktail of cultural anxieties and the figuration of religious authority. In the hands of skilled historians, it may allow us a clean glimpse or two not only of the male demon-expert, but also of the lives of women whose business is invaded, and sometimes eased, by demons and experts both.

Also in this issue: