Beyond Columbus: What DNA Can—and Can’t—Tell Us about Jewish History

Flora Cassen shows how, if used wisely, ancient DNA can serve the work of Jewish history

When a Spanish researcher announced in a documentary last fall that he had identified Columbus’s remains in Seville Cathedral—and that genetic analysis revealed he was Jewish—the story spread through international media like a viral tweet. But the science behind it relied on questionable methodologies. In an article published in El País at the time, Spanish DNA experts noted that José Antonio Lorente, the forensic scientist at the center of the film, had worked on the project for two decades without publishing a single peer-reviewed study. Antonio Alonso, former director of Spain’s National Institute of Toxicology and Forensic Sciences, stated bluntly: “The documentary does not show Columbus’s DNA at any point. We don't know what analyses were done.”

Jewish studies scholars were quick to point out that Jewish identity isn’t encoded in DNA; it is shaped by historical memory, religious and cultural practices, and lived experience. Historian Devin Naar clarified that the notion of Columbus being Jewish has long intersected with broader debates about Jewish belonging. A century ago, it allowed Jews to claim a place in the American narrative. Today, as Columbus’s legacy is associated with colonial violence and oppression, the same assertion provokes discomfort—despite the fact that, even if Columbus were found to have some distant Jewish ancestry, he was a Catholic navigator serving the Spanish crown and never practiced Judaism.

But dismissing this sensational claim shouldn’t lead us to overlook how new advances in genetics can deepen our understanding of history. Until recently, genetic studies of historical origins used contemporary DNA and projected present-day identities onto the past—an approach that reinforced outdated racial categories. This changed in 2012, when scientists sequenced Neanderthal DNA for the first time, opening the door to using DNA from ancient remains in historical research. Since then, the field of ancient DNA has transformed our view of human prehistory.

In my essay, “The Origins of Ashkenazi Jews: Can Genetics Help Resolve an Enduring Historical Mystery?,” set to appear in the next issue of JQR (115.2, Spring 2025), I explore how ancient DNA could also enhance our understanding of Jewish history. For example, consider the debate surrounding the origins of Ashkenazi Jews. Traditional narratives traced their migration from the Middle East through Italy to Germany and Poland, while the controversial Khazar theory posited that Ashkenazi Jews descended from a medieval Turkic kingdom that converted to Judaism.

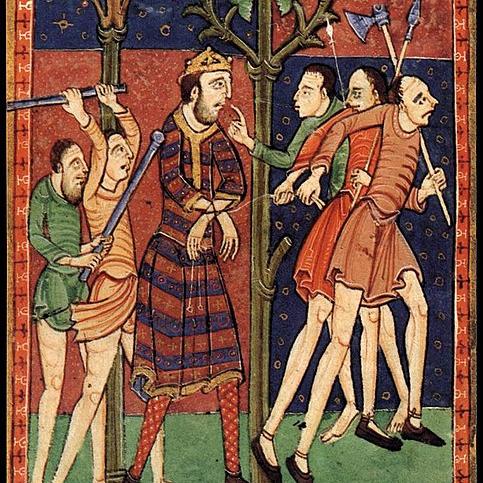

However, the first two studies of Ashkenazi Jewry based on ancient DNA were published in 2022 and have begun to shed new light on the history of this group. The first study analyzed medieval remains from a twelfth-century well in Norwich, England. It indicated that these individuals were likely victims of an attack on the Jewish community during the Third Crusade. DNA analysis reinforced the theory that most Ashkenazi Jews descended from a small group of ancestors but placed that small group earlier than previously thought. The second study examined remains from a medieval Jewish cemetery in Erfurt, Germany, revealing that fourteenth-century Ashkenazi Jews were more genetically diverse than contemporary Ashkenazi populations. Unlike studies based on the DNA of modern populations, these findings reflect the diversity and complexity of past Jewish communities, challenging assumptions of isolation and uniformity.

As these studies and the Columbus saga show, DNA alone does not tell the full story. If historical research requires fluency in multiple languages, ancient DNA can be seen as a new dialect that offers an opportunity for interdisciplinary collaboration between scientists and humanities scholars. While the former can extract biological data from centuries-old remains, the latter are best positioned to provide the cultural, social, and historical contexts that give this data meaning. By engaging in careful, collaborative scholarship, we can use ancient DNA to increase our knowledge of history without falling into the traps of genetic determinism.