“The Art of Drinking Still Presents Some Obvious Difficulties to You”: Schechter the Satirist

The following appeared in the Hebrew periodical Ha-Shachar in 1877 as part of an extended, fictional epistolary exchange between a new Hasid and more seasoned friends.

The newcomer writes:

Here everything is seized with joy and we literally wash ourselves with brandy since the pilgrimage so far has been very strong: every day new guests are coming for the high holidays in thousands and tens of thousands and each of them buys a tikkun [ref. to brandy]. And if there is a gawky one who does not want willingly to buy a tikkun, we steal a coverlet or a prayer shawl from him until he finds himself obliged to buy us whatever we find fit.

Here, my dearest and beloved friend, let me tell you the truth: I cannot drink as much as it is common in the kloyz and in general I am not yet used to it. But I feel it incumbent upon me to drink with every effort I can make until I fall down wherever I sit, so that no one, God forbid, suspects me of being not an accomplished Hasid. Also, I should be grateful to R. Sender the Button, good brother of mine, who instructs me how to sit and drink without measure, non-stop and for its own sake, how to steal a scarf, how to insult a Rebbe who only looks like a Hasid but in reality his heart is replenished with seven abominations, as well as other similar, indispensable things.

The friend’s consoling reply:

I have received your letter indeed. It was a great pleasure to discover that you have peacefully arrived there, and that you started turning into a proper man, and that Reb Sender the Button became your instructor. Though the art of drinking still presents some obvious difficulties to you yet I am convinced that in the nearest future you will become a renowned expert in this field. The crucial thing is not to be an idiot who spills wine on himself but to drink consistently since "if one comes to cleanse himself, he is helped" [see bYoma 38b and bShab 104a].

The image of boozy Hasidim was a regular feature of maskilic and Hebrew renaissance writings of the time (though, like so many Jewish stereotypes, it warred with an opposing one—that of Jews as perniciously sober).

But more surprising is that this exchange, published anonymously, turns out to be the earliest published work of Solomon Schechter.

But more surprising is that this exchange, published anonymously, turns out to be the earliest published work of Solomon Schechter.

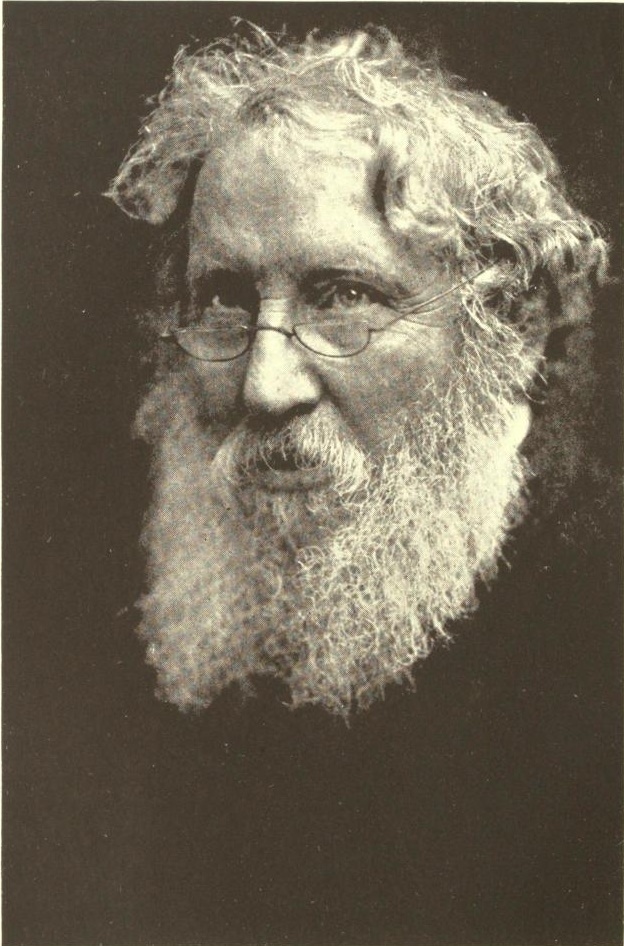

…Yes, that Solomon Schechter—the Cambridge don in rabbinics known for his role in the scholarly dissemination of materials from the Cairo Genizah, his shaping of the Conservative movement in America—and, of course, his editorship of the Jewish Quarterly Review.

What was that Solomon Schechter doing playing with puns and making off-color jokes? As David Starr and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern show in their contribution to the current issue of JQR, the young Schechter was a gifted satirist. As they write, “Schechter knew intimately the rabbinic, kabbalistic, and hasidic world out of which he invented, and with which he contended. Through mockery and parody he created his own dialectics with these legacies, and art ensued.”

Indeed, far from judging Hasidism with an elitist outsider’s eye, Schechter was born into a Russian Chabad family, and accordingly Starr and Stern point out that there is an autobiographical dimension of Schechter’s exaggerated, insulting, and yet cleverly allusive portrayal of that world.

Indeed, far from judging Hasidism with an elitist outsider’s eye, Schechter was born into a Russian Chabad family, and accordingly Starr and Stern point out that there is an autobiographical dimension of Schechter’s exaggerated, insulting, and yet cleverly allusive portrayal of that world.

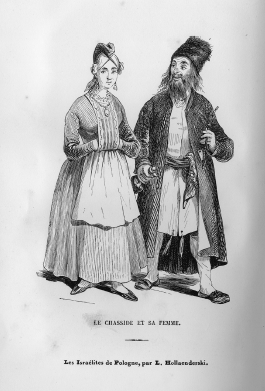

Besides the portrayal of the Rebbe’s followers as laced with brandy, Schechter also turns his wit on the dominant women of the Hasidic household—wife and maidservant.

From R. Fishel, a son of a learned Jewess, to R. Zelig, a husband of the Kishinev Rebbetsin, may she live a long life—

I now have a great desire to become a permanent resident by a hasidic Rebbe and, God willing, I will merit this opportunity. The main reason for this step was my cursed wife, may the earth swallow her! She had the guts and insolence to tell me that I should go and look for some job—despite the fact that I repeatedly told her that she, too, was not sick! … And the idiot that she is has completely forgotten who I am—I, the son of R. Israel, a melamed, and the grandson of the gabai of that old Jewess, may her soul find rest amongst heavenly treasures. Yet at the beginning I thought that all of that was only another crazy whim of hers. But later when I realized that she was insisting on her decision and even demanding from me an account of what I was doing all day long in the kloyzel (as if it was her business), I left her and took to the road and went to the Rebbe. May she stretch her legs from hunger as far as I am concerned.

And another Hasid, R. Hetskul (“who bows to the holy chair standing and serving in holiness by the Rebbetsin, may God prolong her days”), writes:

As it is known to you, the Holy Honor of the Torah Crown, it has already been a few months since the uncle of our Rebbe and tsadik, our local admo”r became been deeply immersed in a black melancholy. It seems he is somewhat sick. … He talks to no one nor allows anyone to him, even his warden. With the exception of his maidservant who makes his bed he is not ready to put up with anyone's presence, even of the holy Rebbetsin, may God prolong her days.

And one Reb Zelig comments to R. Fishel:

Regarding the Rebbe's maidservant, whom you mentioned in your letter, I saw that you have managed to grasp the truth. And even if you are still a baby Hasid yet you managed to realize that our Rebbe's maidservant is different from the maidservant of a common man. The maidservant of a common man is not connected to her master whereas the maidservant of our Rebbe is maidenly connected to him [hi shifḥat rabenu mamash]. And like the whole people of Israel is provided with children, life, and food through the blessings of our Rebbe, likewise on a daily basis here, in our kloyz, the Rebbe provides us with brandy [yayin saraf] through his maidservant.

Fiery and stimulating, these women appear—like the hooch that so obsesses the acolyte R. Fishel—to be at the center of the hasidic universe—and for very earthly reasons. But in time-honored kabbalistic tradition, Schechter’s send-up of these simpletons masks something higher, as he weaves mystical and rabbinic symbols and sayings into the text. Heresy and sexuality, exegesis and stolen scarves, are all rolled together in his youthful meditation on Hasidism.

There’s much more where this comes from. In an appendix, Starr and Petrovsky-Shtern provide a translation of Schechter’s whole extended parody, and draw out numerous threads of the man’s personal, intellectual, and artistic stake in this first foray into the literary arts.

Read Starr and Petrovsky-Shtern’s “Solomon Schechter's Art of Hasidism: Tradition, Parody, and Transmission” with a subscription via Project Muse: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/708220.

The rest of the issue, including some free content, is summarized here.