The Case of Jewish History

Carlo Ginzburg and Francesca Trivellato spoke to the Katz Center about Jews, microhistory, and global paradigms.

A few weeks ago, the Katz Center presented the 23rd annual Joseph and Rebecca Meyerhoff Lecture at Penn, featuring a conversation between Carlo Ginzburg and Francesca Trivellato on the topic of microhistory and global history.

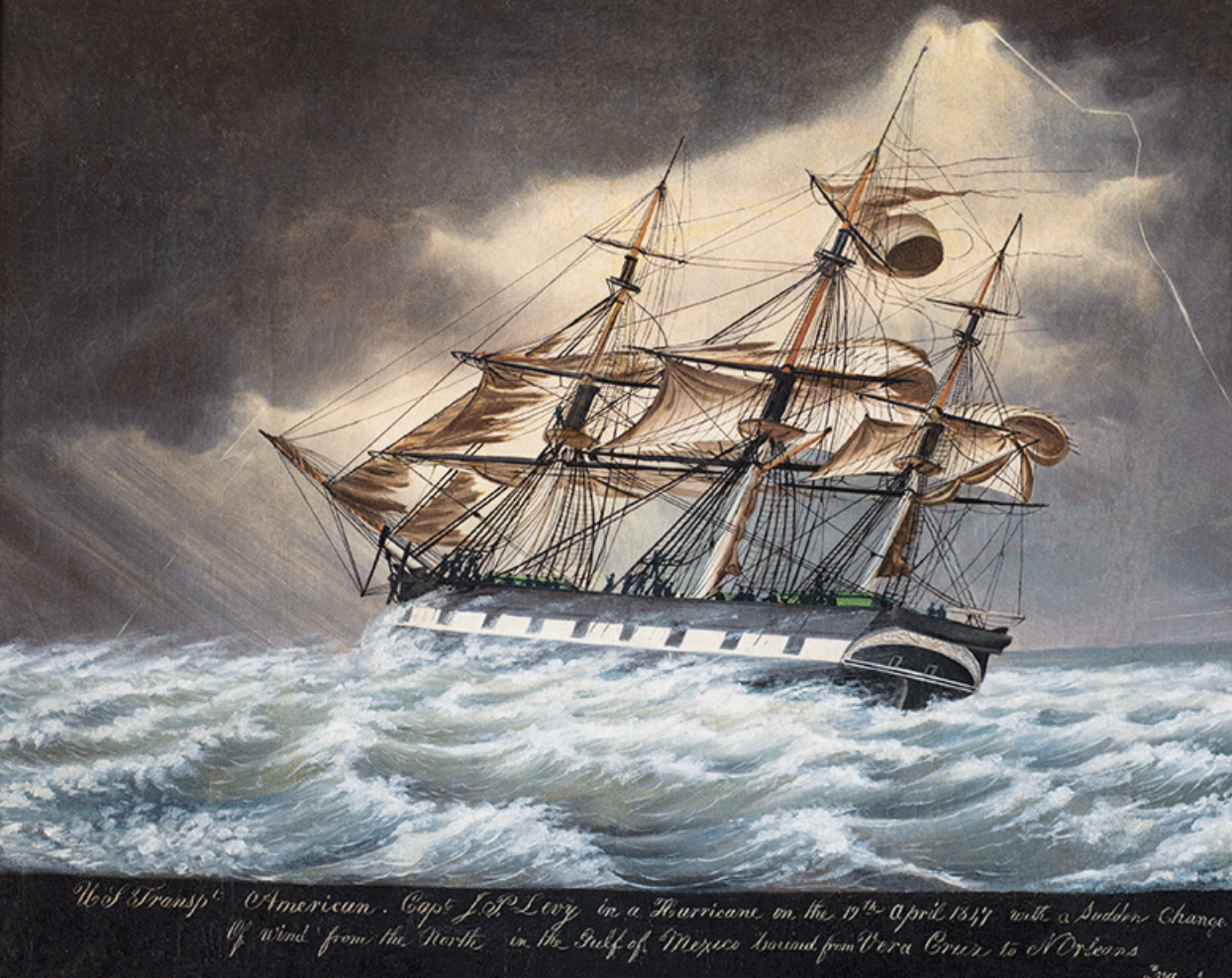

Ginzburg was one of the first to develop the methodology of microhistory, in which the historian seeks a sympathetic and close understanding of one figure or a small group, often running against the grain of the majority or hegemonic culture. The first and best-known work of this kind was his 1976 The Cheese and the Worms. Trivellato, for her part, embraced global history in her 2012 The Familiarity of Strangers on Sephardic Jewish financial networks, and in the process has also explored how microhistory can inform and enrich macrohistory.

Neither of these towering figures operates primarily within the bounds of Jewish studies or Jewish history. Trivellato’s work on Jews grows from a primary interest in economic history. Ginzburg’s ties to Jewish history are even more tenuous—though his pioneering methodology has permeated Jewish historiography as deeply as it has other fields, and in recent years he has offered some comments about how his own Jewish background shaped his research. Their wide-ranging conversation treated that dimension of Ginzburg’s intellectual biography with new depth, and addressed how the micro and macro lenses fruitfully intersect in Jewish historiography.

To begin with, Ginzburg recounted how he worked on witchcraft trials at the very start of his career in order to “rescue the voices and attitudes of the oppressed”—a project that was, as he realized only later, connected to his family legacy as Jews and anti-fascists. He himself had experienced persecution during World War II in Italy, and it was that persecution that, in his words, “turned me into a Jewish child.” His primary sense of Jewishness was related to exclusion and suppression; the Jews, lepers, Muslims, and witches that he later wrote about in Ecstasies: Deciphering the Witches’ Sabbath (1989) were all similarly “excluded” people. Ginzburg memorably described an emotional moment in the archive when, overcome by the violent realities of witchcraft trials, he went outside to reflect, pacing and chain-smoking in the nearby piazza.

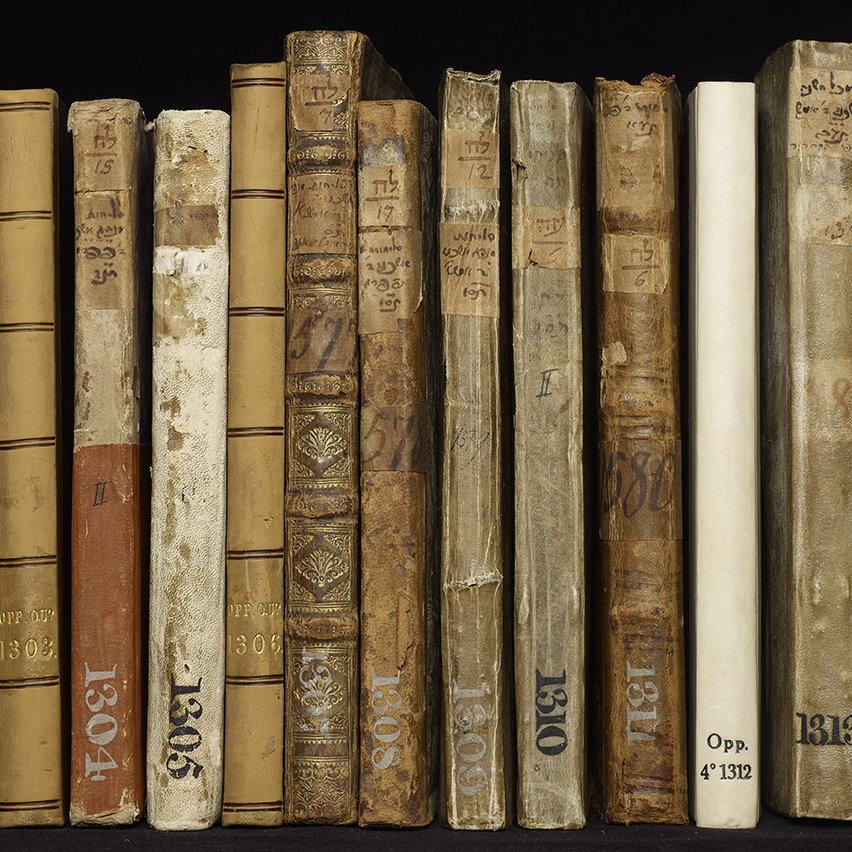

Aside from the inherent humanistic value of retrieving such lost voices and experiences, Ginzburg’s work also shows how paying attention to them can alter the overall view of a historical context. Figures like Inquisitors who would otherwise be read as representing an undifferentiated cultural whole at a certain time are thereby revealed as partial (in both senses of the word): the creators of the archive were only one of many opposing parties, and their records are far from neutral.

Ginzburg also pointed out here how the individual “case” can form a basis for generalization, and his comments on this topic addressed a commonly articulated concern that microhistory as an approach might have a limited capacity to generalize. Against that view, he spoke about how he learned to move from a particular imagined conspiracy among certain marginalized people, closely localized in its detail, to sense of how such particulars can be read as “paradigmatic.”

From the “paradigmatic” to the “global,” there are innumerable ways to expand on individual cases, and Trivellato asked Ginzburg to comment on how microhistory relates to global history. In his reply, he suggested that global history deals with “an ongoing process … connecting more and more [of] the world in its diversity and its inequalities.” Microhistory’s attention to precisely those diverse and unequal experiences can thus be seen as leading to, and as a part of a trajectory toward, global history.

At the same time, the very process of embedding those lost voices in a historical narrative may betray their authenticity. In a final exchange, Trivellato asked Ginzburg about his idea that the very notion of historical perspective is itself rooted in the legacy of Christian supersessionism. “Academic historians work with a secularized notion of historical perspective,” she acknowledged, but asked if it is nevertheless inexorably tied to the Christian (and hence also European, colonialist) legacy. “How do we think about the potential universality of the notion of historical perspective outside or within the constraints of this Augustinian legacy?” Do all cultures even have a notion of historical perspective?

Ginzburg’s answer referred to his essay “Our Words, and Theirs: A Reflection on the Historian’s Craft, Today,” in which he explored the disconnect between the categories of the observer and the actor in any work of historicization. He related the historical gaze to that of the Christian Augustine, who struggled to embrace Judaism as fully true while also moving beyond it. Likewise, the historian must reconstruct things on their own terms even while looking at them from a distance. “Everybody working in history, not only in Europe, but all over the world, is compelled to use this notion of history, which is my view rooted in this ambivalence of the Christians vis à vis the Jews. I’ve been and I still am puzzled and troubled about this issue.”

As a historical subject, Jews and Jewish culture are ripe subjects for the interlocking dimensions of microhistory and global history. In many contexts Jews are a subaltern, a repressed or marginalized minority whose inner dynamics and ideas, understood from within, counteract and hence illuminate majority culture. As a global diaspora, their history is also well suited to a macrohistorical approach, and as Trivellato has shown, that can mean attention to a small minority in a transnational context. As this remarkable conversation unfolded, we saw how the case of Jewish history is paradigmatic in both microhistory and global history in both constructive and perpetually challenging ways.