Katz Center Fellow Britt Tevis on “Mythical Jewish Arsonists” and Anti-Jewish Discrimination in U.S. History

This blog post is part of a series focused on the research of current fellows. In this edition, Katz Center Director Steven Weitzman sits down with Britt Tevis, a historian with special interests in law and Jewish studies.

Steven P. Weitzman (SPW): You are one of the few Katz Center fellows in my time as director who combines training in history and the law (although we will have several next year in a year focused on Jews and the law). Can you tell us a bit about what led you to the study of legal history, intellectually and/or personally?

Britt Tevis (BT): I came to study legal history somewhat accidentally. I first encountered the subfield as a result of an internal struggle about what career path I ought to pursue.

For most of my childhood and adolescence, I wanted to be a lawyer. When I was around five years old, I learned that people who fought injustices were called lawyers. Like many children, I viewed the world in absolute terms and had a strong aversion to what I considered unfair. The idea that there was a type of adult whose purpose was to right wrongs was reassuring. When I was about twelve, I developed Type 1 diabetes, a chronic autoimmune disease. My diagnosis felt like a personal injustice, which only intensified my preoccupation with notions of justice and fairness. In short, before I finished high school, I had already decided to go to law school, because I thought being a lawyer would enable me to rectify what I perceived as unjust.

When I started college, I declared political science as my major with that goal in mind. Then I fell in love with the field of history and with Jewish history specifically. What I learned in my history classes enabled me to understand the world in ways that felt absolutely essential. By the time I graduated I had concluded that I would not be able to function as an adult without formal training in the field. (In retrospect, I recognize that this conclusion was erroneous, not to mention hilarious.) At the same time, I was equally committed to pursuing a law degree, because I had imagined myself as a lawyer for most of my life. Unable to choose one path, I decided to go for two degrees—a Ph.D. in history and a J.D.

After college, I enrolled in graduate school at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the University of Wisconsin Law School. During my first semester in Madison, I went to the Wisconsin Historical Society to find a topic for my Master’s Thesis. In what was an admittedly unimaginative search of its collections, I approached an open computer and typed “Jewish lawyer.” The first name to appear was Jacob Panken, who was the first judge elected on a Socialist Party ticket in the United States. It was while researching Panken that I first encountered legal history. The subfield offered me an intellectual orientation that bridged the gap between what I was learning in the history department and what I was learning in law school. It answered questions I had about power and politics, and proved to be an incredible foundation for thinking about American Jewish history.

SPW: What research project are you pursuing at the Katz Center this year?

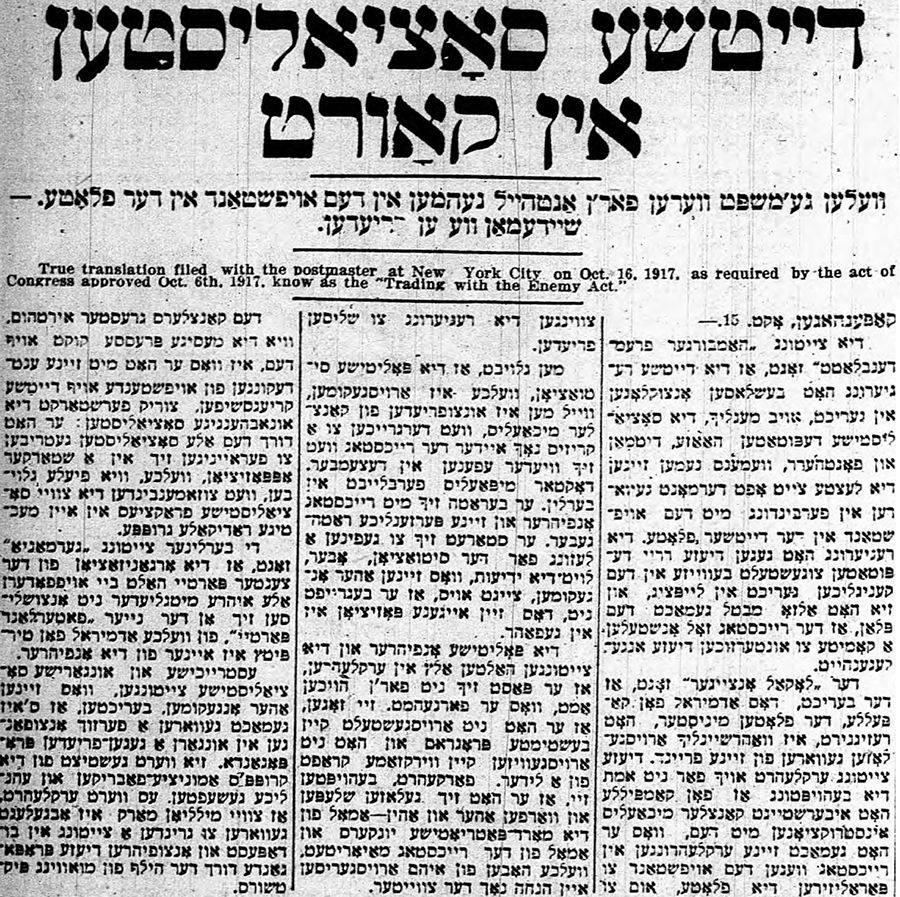

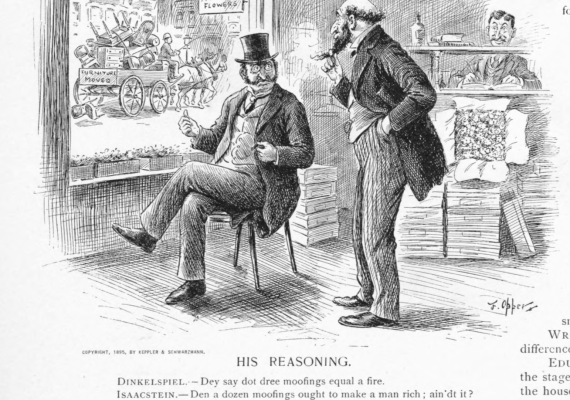

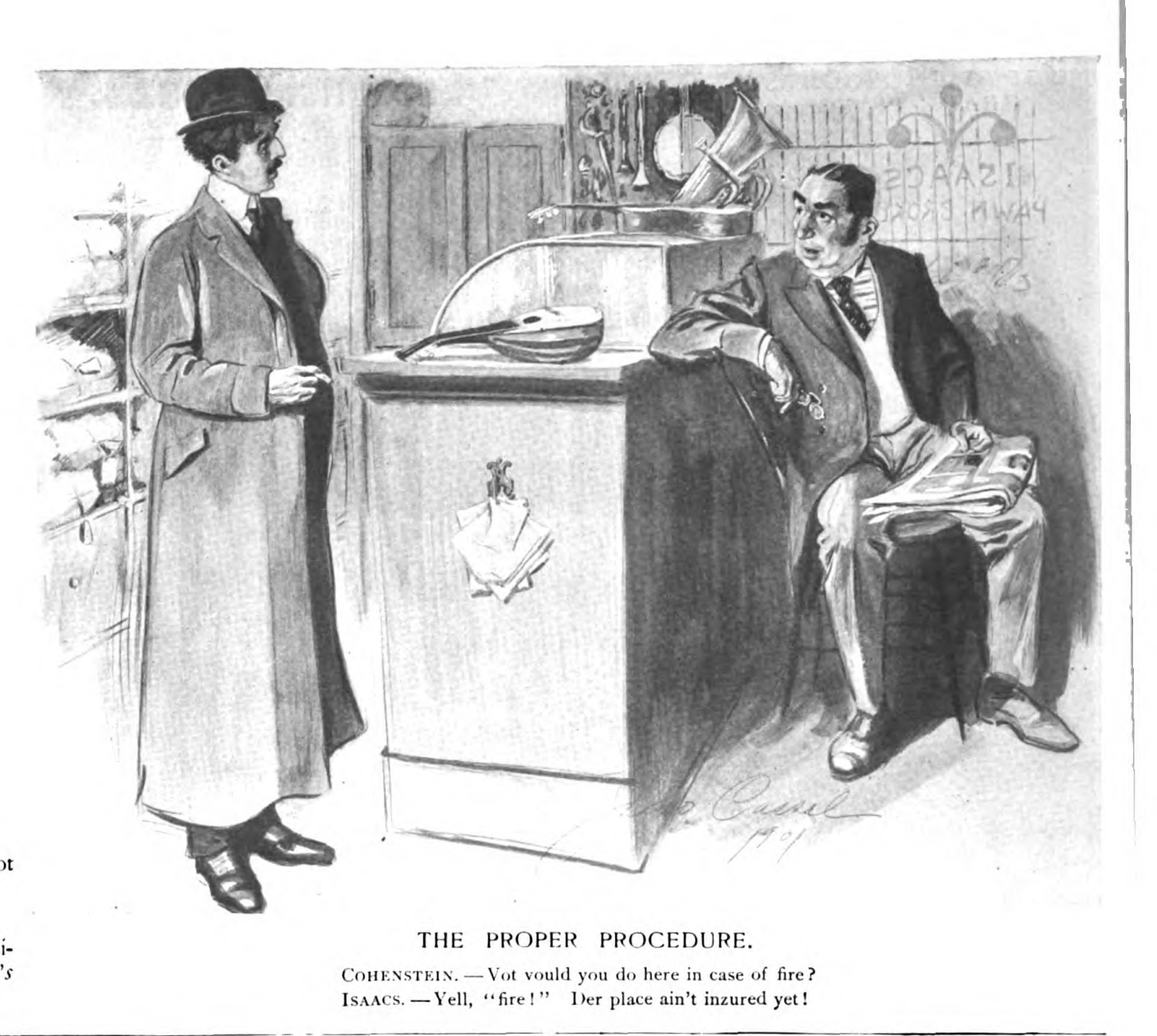

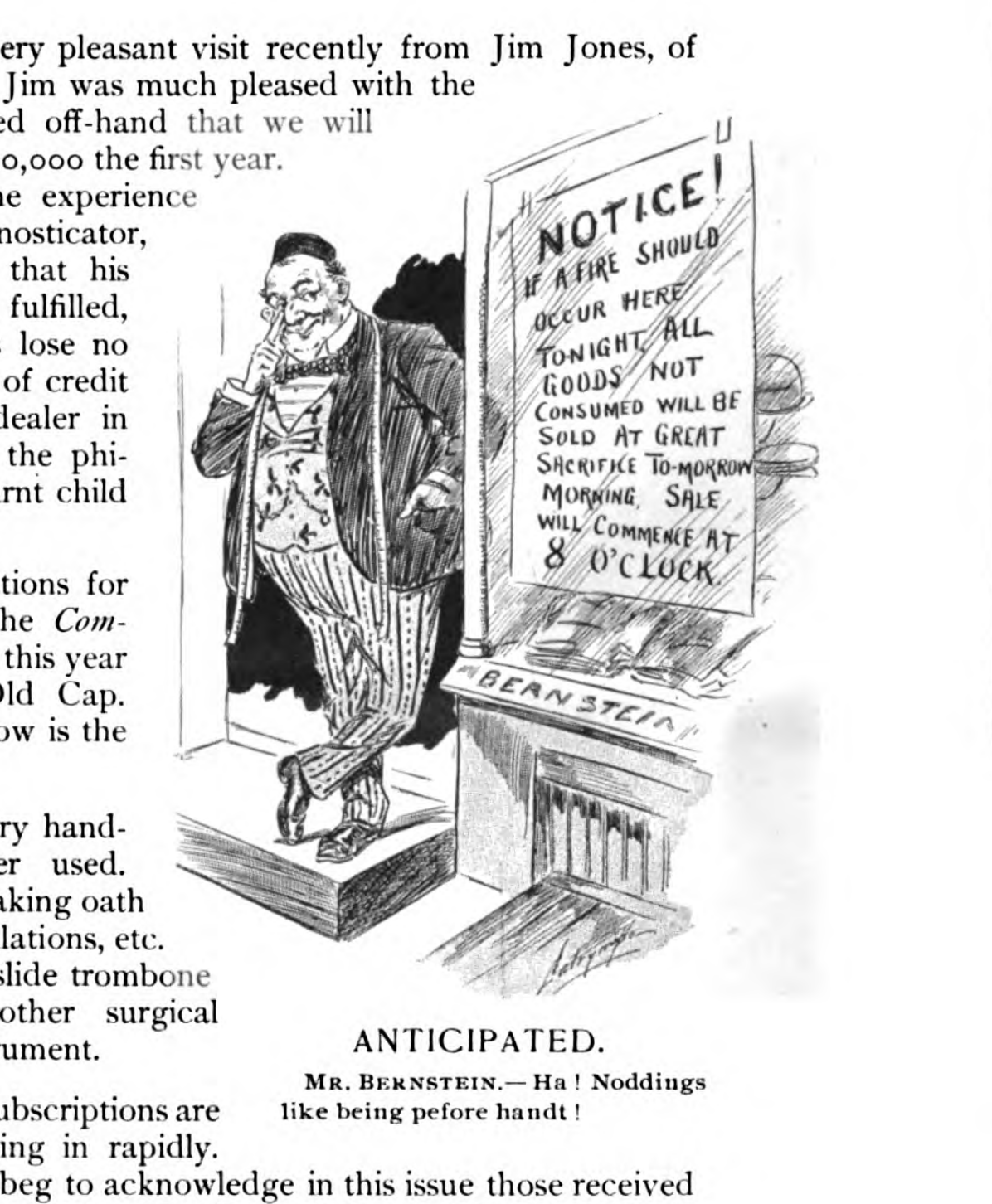

BT: I’ve been researching the phenomenon of Jewish arsonists in the United States. Most historians up until this point have identified arson—the act of intentionally burning one’s property—as a crime that late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Jews were particularly inclined to commit. Yet, I have found significant evidence that shows that profit-driven insurance companies colluded with local and state officials to frame Jews as a collective for this crime. Between the 1890s and 1940s, the fire insurance industry and urban fire departments racialized Jews as arsonists by repackaging allegations about Jews’ obsession with money into accusations of insurance fraud. They spread the idea that Jews were born arsonists—an idea I’ve termed the “mythical Jewish arsonist”—in industry publications, which were disseminated nationwide, and by directly appealing to city fire marshals. Their efforts, aided by local police forces and courts, resulted in the Jews’ criminalization. Popular depictions of Jewish arsonists, which spread from industry publications to the broader culture, reified perceptions of Jews as incendiaries (e.g., giving rise to the stereotype of the “Hebrew firebug”). Jews frequently found it impossible to overcome the power of this stereotype in court, resulting in tragic outcomes such as imprisonment, bankruptcy, and even suicide. Appellate cases and press coverage of local trials illuminate the range of injustices involved in Jewish arson claims.

This history is tragic and alarming. It certainly does not complement what we think we know about American Jewish history. It has been both exciting and disconcerting to research.

SPW: Can you give us a sense of how your research alters our understanding of anti-Semitism in the U.S.?

BT: For many decades, American Jewish historians have advanced the idea that the United States is “exceptional,” i.e., different than European countries. A major component of this argument is the claim that, unlike in Europe, anti-Semitism in the United States has been an insignificant force—fleeting and more or less harmless. For the most part, American Jewish historians have argued that when anti-Jewish animus has materialized, it has been in social contexts. Relatedly, they’ve argued that neither the law nor the state has played a role in perpetuating anti-Jewish sentiments.

My research challenges these long held ideas by revealing the ways in which the state condoned and sometimes promoted anti-Jewish animus, for example, by prosecuting Jews for arson under extremely murky circumstances. Reading the text of the U.S. Constitution and noting that nothing in it specifically discriminates against Jews and then asserting that, therefore, U.S. law doesn’t discriminate against Jews, fails to account for the breadth, operation, and evolution of American legal norms.

SPW: Does it also alter our understanding of U.S. law? If so, how?

BT: For years, legal historians have revealed the many ways in which people (mainly white Protestant Christians) have used local, state, and federal law and common law (judge-made law) in order to discriminate against given populations—Black Americans, of course, as well as Asian, Latino, and Native Americans. Jews are ordinarily overlooked in these analyses. My work constitutes an effort to apply a similarly critical eye to U.S. law in order to illuminate how people have used legal norms and procedures to discriminate against American Jewry.

SPW: This is an era when many institutions, including companies, are having to face up to injustices committed in earlier generations. Given its role in the history you have uncovered, I was wondering whether the insurance industry today has at least acknowledged the role of this and other prejudices in its history—whether that be anti-Semitism, racism, or other forms of prejudice? Do you know whether the insurance industry is facing a reckoning of any kind, or do you have any views about how it should address the kind of history you are bringing to light?

BT: In the past five years or so, some American insurance companies have faced increased scrutiny for their role in supporting the institution of slavery. Journalists such as Rachel Swarns and historians such as Sharon Ann Murphy have shed light on the important role that insurance companies played in enriching slaveholders. It is interesting to note that at least one of these companies, Aetna, also played a significant role in advancing the idea that Jews were prime suspects for arson.

As far as I know, no insurance company has publicly acknowledged their role in perpetuating anti-Jewish stereotypes that cast Jews as arsonists. Likewise, to the best of my knowledge, historians have not yet revealed the central role of insurance companies in generating these ideas in the United States. I think it is unlikely that the companies, which have little interest in uncovering such activities, would independently acknowledge this aspect of their past. It seems more likely that the current employees and executives at these respective companies do not know their companies’ history and are therefore precluded from making amends.

Further, I have only begun my research into this history. Though I have found a significant number of insurance companies that were complicit in spreading the stereotype of the Jewish arsonist and though some of these companies remain in operation, I have not directly linked the actions of a particular insurance company with the wrongful prosecution of a particular Jewish defendant for arson. That isn’t to say I won’t, but it hasn’t happened yet. In short, given the absence of evidence of a direct, specific harm committed by one of these companies, it is somewhat more understandable that they have not acknowledged their culpability in spreading a malicious and harmful idea about Jews.

When I eventually publish this research, this is something I may look into advocating.

What a brilliant question. Thank you.

SPW: Despite the pandemic, which has forced the fellowship program online, it seems to me that the fellows have successfully formed a genuine intellectual community, which is to their great credit. I wanted to ask whether the experience this year has inflected your understanding of your research in any significant way, and if so, how?

BT: If anything, to my mind, this year has only underscored the importance of archives as institutions that enable historical research. Most historians (including this historian) love archives and revere archivists. Without these repositories for document collections and absent the individuals who organize, maintain, and manage them, historians have little to use in order to answer the historical questions we pose. Asking a historian to produce historical research without granting them access to the appropriate archives is akin to asking a lawyer to try a case without having completed the process of discovery. You can have a hunch about how or why something happened, but you need evidence to make your case. Historical evidence, more often than not, is tucked away in a manila folder in a brown or gray box, which is sitting on a shelf in an archive.

During the COVID-19 closings, many archivists digitized collections and shared requested documents, but this type of exchange largely precludes the moments of unexpected discovery that in-person archival research permits. Ideally, when I visit a given collection, I will read documents that I’ve anticipated seeing and I will encounter something that I couldn’t have imagined existed. Both types of research moments are important, but it is the latter that ultimately reshapes what I think about a particular idea, event, person, etc., and these are the types of discoveries that have been curtailed this past year.

In short, I am grateful for how many archives have enabled historians to continue their work during the pandemic to the best of their abilities, and I am eagerly anticipating the opportunity to do in-person research.