Katz Center Fellow Ayelet Brinn on the American Yiddish Press and the Historical Roles and Contexts of the Media

This blog post is part of a series focused on the research of current fellows. In this edition, Katz Center Director Steven Weitzman sits down with Ayelet Brinn, a historian of American Jewish culture whose research examines the history of American Jewish print.

Steven P. Weitzman (SPW): Ayelet, can you tell us a bit about the project you are working on at the Katz Center?

Ayelet Brinn (AB): My research so far has focused on the history of the American Yiddish press at the turn of the twentieth century, and its role in mediating between American and Jewish cultural spheres. My dissertation focused on the central role questions of women and gender played in shaping the development of the American Yiddish press—when and why different Yiddish newspapers began including features explicitly targeting a female audience, the changing gender breakdowns of newspaper staffs, and the various symbolic or rhetorical roles that women readers or writers played for the producers of Orthodox, radical, and non-partisan Yiddish newspapers in different stages of their development. I’m currently working on turning this research into a book.

During my research and writing process, I kept coming up against interpretive questions about the way the history of the Yiddish press in America has been written, as well as questions about the sources we have with which to reconstruct the history of Yiddish culture in America, both primary and secondary. For my research at the Katz Center this year, I decided to focus explicitly on these questions of interpretation—thinking through how the history of the Yiddish press has been interpreted in different moments and why, and what this can tell us about broader questions in American Jewish history, American foreign-language culture, and Yiddish culture.

SPW: Have you ever worked as a journalist yourself? If so, did you carry anything from that experience into this project. If not, how did you get interested in the history of the press?

AB: I actually worked on the staff of my high school and college newspapers, first as a news editor then as a copy editor. Though I’m not sure I’ve made a direct connection between these experiences and my research until now! I think the main takeaways that I bring to my research are thinking through the processes through which newspapers come about—the editorial deliberations behind the articles we read, who decides what kinds of features or news coverage is included in a given issue of the paper. It also turned my attention to newspapers as social spaces—the importance of who was in the newspaper office and how their interactions affected the content and style of the newspaper itself.

SPW: Your research has many dimensions and is ongoing, but for our audience, can you share a nugget or two about what you've learned about the history of Yiddish newspapers like the Forward that historians haven't sufficiently appreciated in the past?

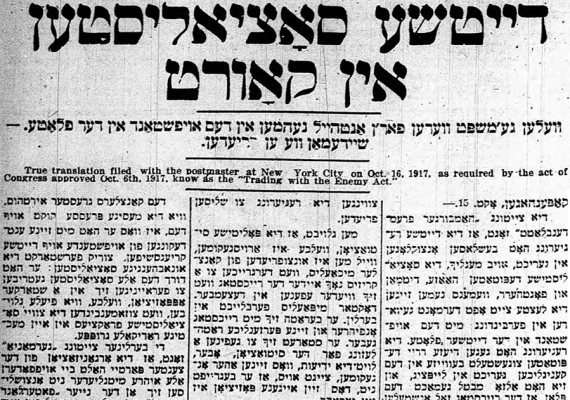

AB: Sure! The research I presented this month at the Katz Center focused on attempts by the US government to censor foreign-language newspapers, including the Yiddish press, during World War I, and the various strategies Yiddish newspapers like the Forward used to navigate this particularly complex moment in American history. Often when discussing American Jewish history, we tend to focus on the comparative freedom of expression afforded to Jews in America, but this moment highlights that this freedom was not always guaranteed, both for Jews and for American citizens in general.

SPW: During a recent discussion of your work, some fellows made connections to the study of media today. Can you give us a sense of how a newspaper in the era you study differs from a newspaper now, in terms of how it understood its mission?

AB: I think one important thing to keep in mind is that newspapers at the turn of the twentieth century—both in Yiddish and in English—had very different relationships to objectivity than what we expect from newspapers today. We can certainly debate whether many newspapers today (or other forms of media today) really strive to be objective. But in the early twentieth century, that wasn’t necessarily something newspapers like the Forward or the Jewish Daily News were even aiming for. So that’s definitely something to keep in mind when reading older newspapers; we need to ask questions about why they’re reporting what they’re reporting, and how they’re covering issues. [For more on the history of objectivity in the American English-language press, see Michael Schudson’s Discovering the News (1978)].

It’s also helpful to consider the various roles that newspapers at the turn of the twentieth century, especially Yiddish newspapers, played in readers’ lives. In addition to being sources for news coverage, they were also the major venue for Yiddish literature, both prose and poetry, and their advice columns and other features were crucial for helping readers learn about various aspects of American culture and helping them navigate American institutions. So in some ways, newspapers were also tour guides, encyclopedias, social service agencies, literary venues, and played many other roles in readers’ lives along with conveying the news of the day.

SPW: Your work uses the history of the Yiddish Press to draw some intriguing and resonant conclusions bearing on the history of the freedom of press in the US. Can you share an insight or two into what your research is revealing about the history of this very fundamental freedom?

AB: One important element that this research highlights is the ways in which concepts we view as fundamental freedoms—such as freedom of the press or freedom of speech—have actually meant very different things at different times in American history. So as a historian, I have to constantly make sure that I’m thinking about these institutions and concepts in the proper historical context—what I expect from a newspaper today is not necessarily the same as what readers or editors or the government expected from a newspaper a hundred years ago. And what I assume is meant by freedom of the press also is not necessarily the same.

Lead image: “German Socialists in Court,” Forward, October 16, 1917.