The Future of the YIVO Library

The news that the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research responded to a budget crisis this month by laying off its entire library staff came as a shock to the Jewish studies academic community, which responded with an outpouring of concern.

The news that the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research responded to a budget crisis this month by laying off its entire library staff came as a shock to the Jewish studies academic community, which responded with an outpouring of concern.

My own connection to YIVO dates back to 1990 when as a young college graduate I was hired to work in the YIVO Archives. At the time the first comprehensive overview of YIVO’s archival holdings was underway, and I watched as Fruma Mohrer, a member of the YIVO staff from 1978 until her recent layoff, meticulously checked over 1,000 collections to compose the descriptions that became the basis of today’s online guides. I was also privileged to work with the physically petite yet imposing Dina Abramowicz, a Vilna native and YIVO librarian from 1947 until her death in 2000.

Later as a graduate student writing a dissertation on the history of YIVO, and in my subsequent scholarly work, much of my research would have simply been impossible without the assistance of Zachary Baker and Brad Sabin Hill when they each served as the head of the library. Dr. Lyudmila Sholokhova, who in her previous post was instrumental in the rediscovery of the legendary An-sky folklore collections in Kiev, continued this tradition of deep knowledge of the YIVO collections and dedicated public service.

*******************************

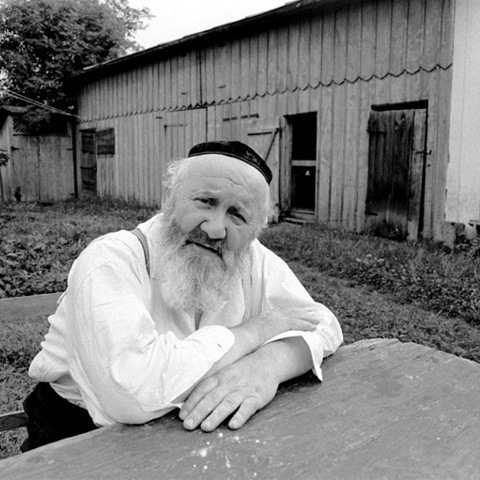

When YIVO began its work in Vilna (then Wilno, Poland and today Vilnius, Lithuania) in 1925 as the world’s first center for Yiddish scholarship, one of its top priorities was creating a Bibliographic Commission to track all publications in the Yiddish language. Within a few months the Commission had an array of correspondents across the Yiddish-speaking Diaspora, from Moscow to Buenos Aires. Later, as YIVO’s zamlers (collectors) began sending older books and newspapers to the institute’s headquarters in Vilna, a library was founded to house them. Thus from its inception, the YIVO Library functioned in close rapport with its patrons while serving as a kind of national institution for Yiddish-speaking Jews worldwide.

The library grew over the next decade and a half until the Nazi occupation of Vilna. The Germans turned former YIVO staff members into slave laborers, compelling them to select items for shipment to Germany and to destroy the rest of the collections that they had painstakingly built and organized. A portion was rescued by a group of these laborers, the so-called Paper Brigade, who put their own lives at risk in the process. Another portion was recovered after the war in Germany and brought to YIVO’s new headquarters in New York, where it joined the collections of the institute’s American branch. Together, they became the basis of one of the world’s great Judaica libraries.

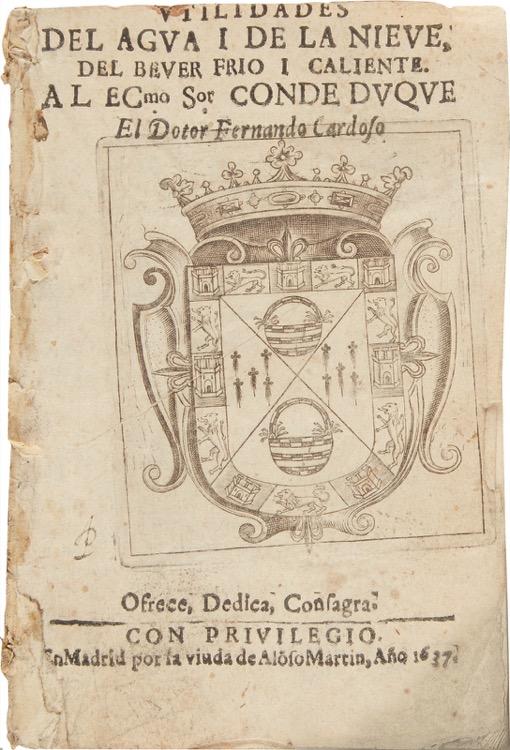

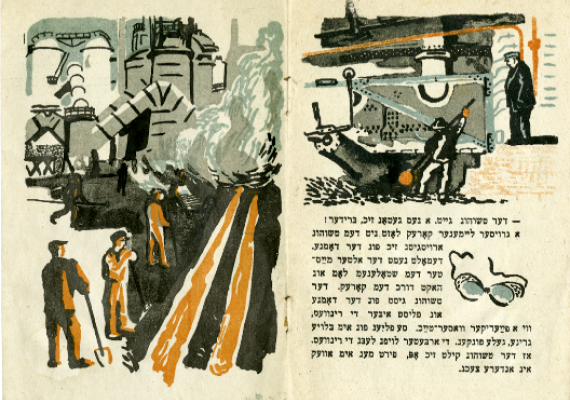

Today, YIVO’s 40,000-strong Yiddish collection is the largest anywhere, featuring items dating back to the seventeenth century, though Yiddish works comprise only 10% of its total holdings. With 400,000 volumes in at least 12 major languages, the collections include 25,000 rabbinic works, 6,000 rare Nazi propaganda publications, an important Ladino collection, and unique items in Slavic and Romance languages.

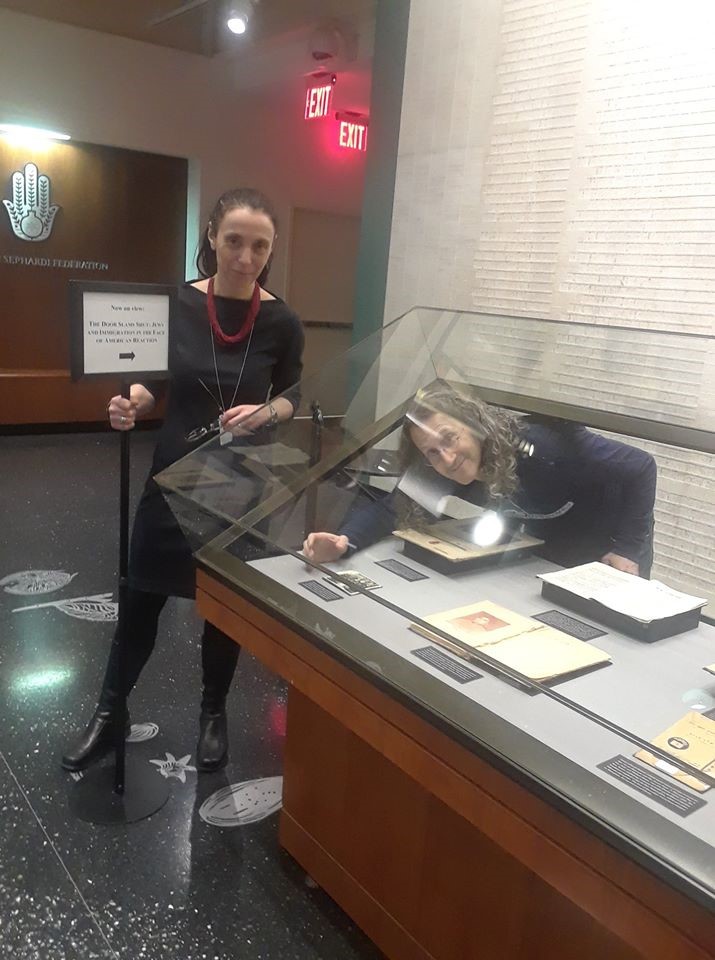

Now without a single librarian, YIVO has assured its patrons that its holdings can still be accessed via the centralized reader services in the reading room of the Center for Jewish History, where YIVO is located. This announcement implies that the library staff did little more than page books, an assumption that ignores major research projects, including: cataloging the personal library of the renowned Yiddish writer Chaim Grade; researching the provenance of items inherited after World War II; supplying material for exhibits at the Jewish Museum as well as at the Center for Jewish History; and supporting the Vilna Project, YIVO’s landmark effort to catalog and preserve the portions of its pre-war collections that came to light in recent decades after surviving the Nazi and Stalinist regimes in Lithuania. In addition, the library responds to thousands of research requests annually from around the world, many requiring specialized knowledge that CJH librarians or other YIVO staff simply cannot replicate.

*******************************

Since my student days, research in Jewish studies—as in the humanities as a whole—has undergone a sea change. To take one example, none of us misses hours spent in dark rooms scanning reel after reel of blurry microfilm, hoping that an obscure footnote will lead to the article we sought. Today, access to the Yiddish press has been transformed by online tools such as the invaluable Index to Yiddish Periodicals and the Historical Jewish Press, both projects of the National Library of Israel. Yet such intimate engagement with our sources—however headache-inducing—had unexpected payoffs. Dr. Eddy Portnoy, now Academic Advisor and Exhibitions Curator at YIVO, found the sources for his book Bad Rabbi while scanning the press for other material for his dissertation research.

Moreover, electronic research tools, like their print predecessors, are only useful if people know that they exist and know how to use them effectively. Such knowledge can only be gained from the most important resource of all: the librarians and archivists with the training to guide patrons to the information they seek. As an instructor in YIVO’s Uriel Weinreich Program in Yiddish Language, Literature, and Culture, I have met advanced students who are unfamiliar with the Index to Yiddish Periodicals or the still-indispensable print volumes of the lexicons of Yiddish writers. This situation, sadly, reflects a wider culture where access to information is instantaneous and expertise is devalued. In this environment, it is not surprising that donors are reluctant to support the maintenance of print collections or the salaries of staff who patiently track down the answers to patrons’ queries.

*******************************

YIVO’s budget woes are also an enduring part of its history. When the renowned historian Simon Dubnow was first told of the plan to found YIVO, he reacted with skepticism:

“First there must be found a wealthy man who will give several tens of thousands of dollars for the institute—we are after all a people of paupers and live from charity—and the second and third year we must pray to God that he (the wealthy man, that is) doesn’t go bankrupt.”

In fact, YIVO relied on contributions from thousands of dedicated zamlers, but the small sums sent by these impoverished supporters could not sustain the institute’s budget. On YIVO’s tenth anniversary, Dubnow was still lamenting, “Where can one find a Jewish Carnegie or a Rockefeller for our YIVO?”

Dubnow’s question still resonates today, with the added caveat that the priorities of donors, when they can be found, do not always align with the institute’s core mission. Yet it is incumbent on all research organizations—in Jewish studies and the humanities as a whole—to recognize the importance of libraries and to prioritize them in their fundraising and institutional planning. Like thousands of others, I have only been able to carry out my academic work because of the generous assistance of YIVO’s professional staff. The next generation of students and scholars deserves the same privilege.