The Wayfarer’s Prayer in manuscript: Karp BVIII.7

Penn Libraries' Rare Judaica Cataloging Librarian examines a special case of the Wayfarer’s Prayer.

Upon cataloging manuscript ephemera from the Abraham J. and Deborah Karp Collection of Judaica at the Penn Libraries, one item caught my eye – something very uncommon. What I mean by this is that there is no real comparable equivalent to this manuscript that I have seen in other collections or at Judaica auctions.

The Wayfarer’s Prayer is mentioned in the Babylonian Talmud (which quotes it from an earlier source) instructing that one should silently recite a prayer upon leaving a city border while traveling. The text of the prayer translated into English is as follows (translation by Sefaria.org; brackets are mine, as only the Ashkenazic custom recites the final blessing):

May it be Your will, Eternal One, our God and the God of our ancestors, that You lead us toward peace, support our footsteps towards peace, guide us toward peace, and make us reach our desired destination, for life, joy, and peace. May You rescue us from the hand of every foe, ambush, bandits and wild animals along the way, and from all manner of punishments that assemble to come to Earth. May You send blessing in our every handiwork, and grant us peace, kindness, and mercy in your eyes and in the eyes of all who see us. May You hear the sound of our supplication, because You are the God who hears prayer and supplications. [Blessed are You, Eternal One, who hears prayer.]

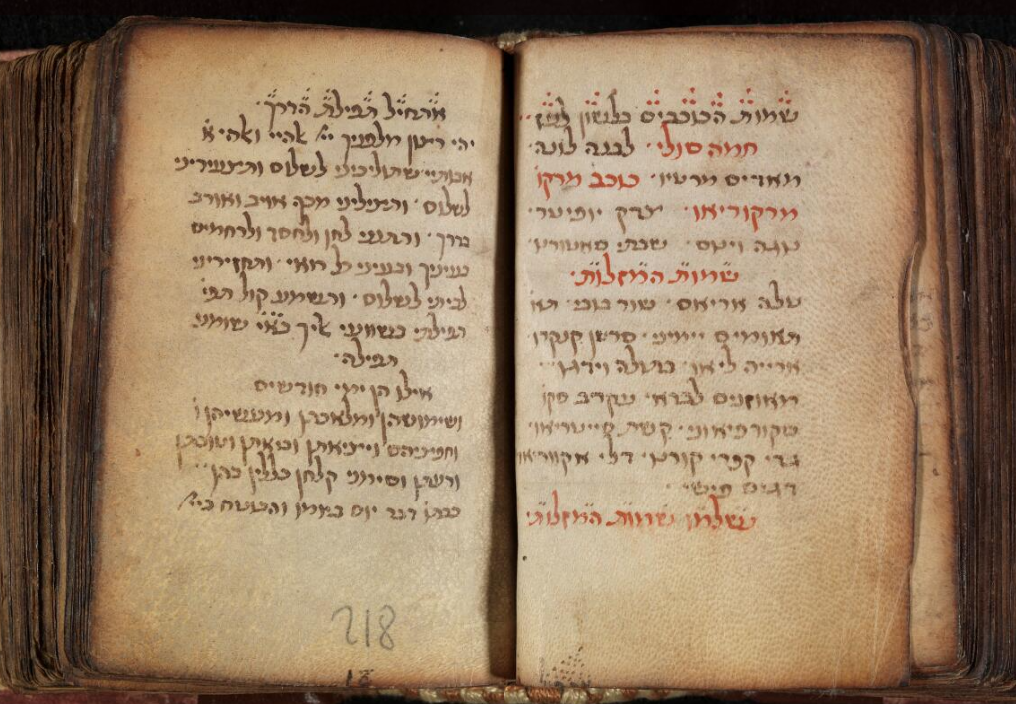

While the Wayfarer’s Prayer does exist in manuscript, its appearance generally follows one of two patterns. The first is that it shows up in prayer books among the berakhot (daily blessings) recited upon special occasions, as in this manuscript Siddur of Roman rite, held in the collection of the Biblioteca Palatina. The prayer is situated at the end of the volume, between a dictionary of the names of the planets, stars, and constellations from Hebrew to Latin and astrological predictions based upon the Zodiac and the solar calendar.

The second type of contemporary manuscript documentation of the Wayfarer’s Prayer is seen occasionally with the proliferation of cabalistic manuscripts in Ashkenaz during the latter 16th and especially the 17th centuries. This type of composition is not a liturgical one – it is one of cabalistic reinterpretations and highlighted verses and intentions, or selections from the Zohar, to be recited for divine assistance while traveling. As with the liturgical manuscript forms, these compositions were added to manuscript codices of cabalistic materials. One example is found in a collection of verses and meditations written by Mordekhai b. Ya’akov Prszybram of Prague (1620?–1675), currently held in Amsterdam's Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana.

The origin of the Wayfarer’s Prayer in Nusaḥ Ashkenaz (the medieval Franco-German rite) can be seen amid the liturgy in Mahzor Vitry, one of the earliest codes of liturgy and Jewish law of the Middle Ages; integrally composed by the school of Rashi (Solomon b. Isaac of Troyes, 1040–1105) with later French and German additions, it was representative of the rite of Ashkenazic Jews since the earliest days of their liturgy.

I am including this information because it is important to highlight when contrasting our manuscript with the regnant manuscript practices of documenting and reciting the Wayfarer’s Prayer. The essential similarity of these two practices is that, while it was important to know and to recite, it was sufficient to record it and have it committed to memory. This is why this text was so irregularly produced in manuscript during this period.

One final example – before I exhibit our manuscript – is one I saw written in a printed volume of an Ashkenazic halakhic text, today in the collection of Columbia University Libraries – the Sefer ha-Rokeaḥ by R. Eleazar of Worms, printed in Fano by Gershom Soncino in 1505 (this volume is otherwise well-known for being the first Hebrew printed book with a title page). In this version, a 16th-century Ashkenazic scribe carefully copied the Wayfarer’s Prayer to the end of the printed index at the beginning of the volume.

The chances of this volume having been carried around by a traveler so that he’d be able to recite the prayer is close to impossible. The reason that a professional scribe wrote the prayer here was so that the owner would be able to use it to commit to memory and therefore recite it freely each time he journeyed on the road. This example is a variation of the categories mentioned earlier – that the Wayfarer’s Prayer was committed to extraneous documentation and used for reference only.

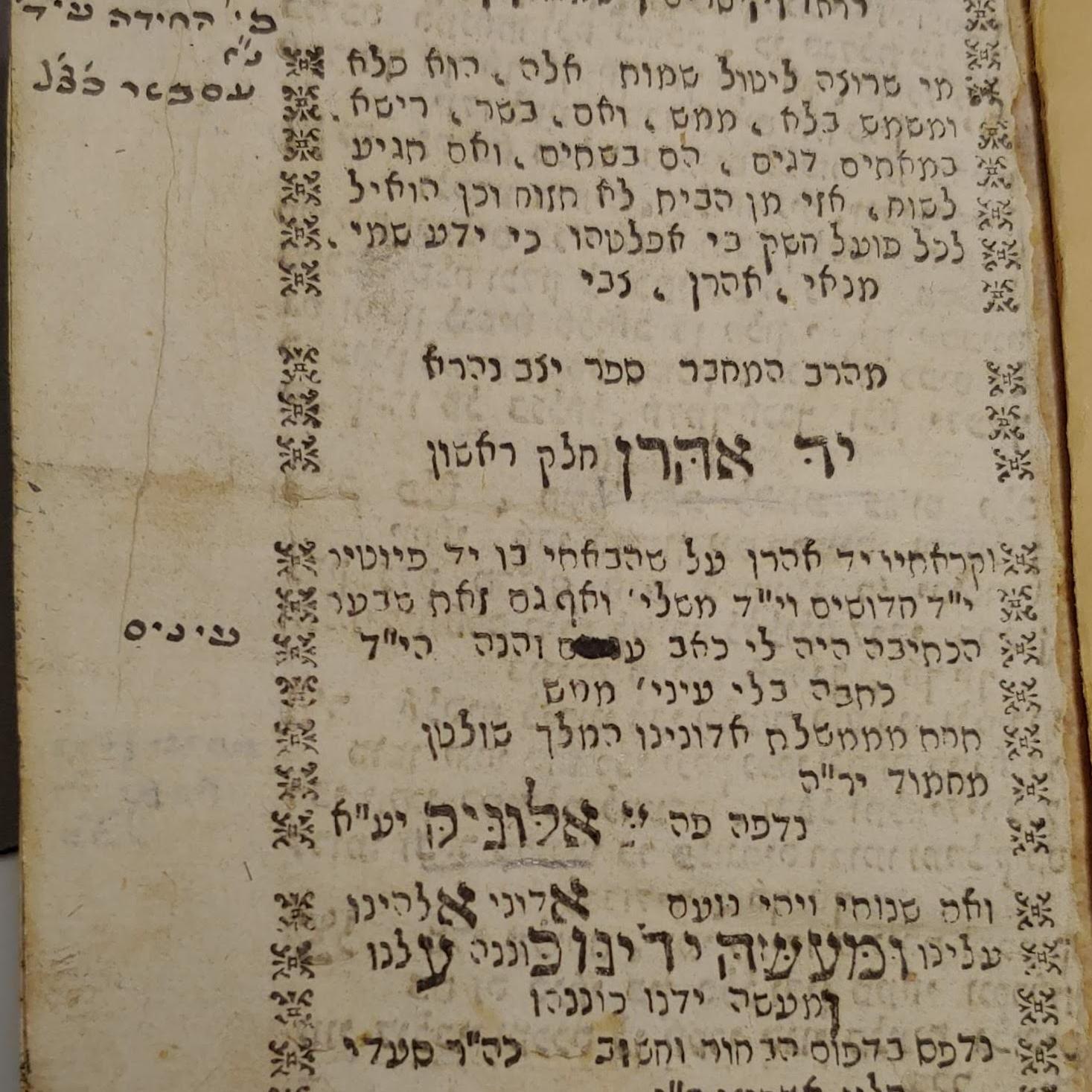

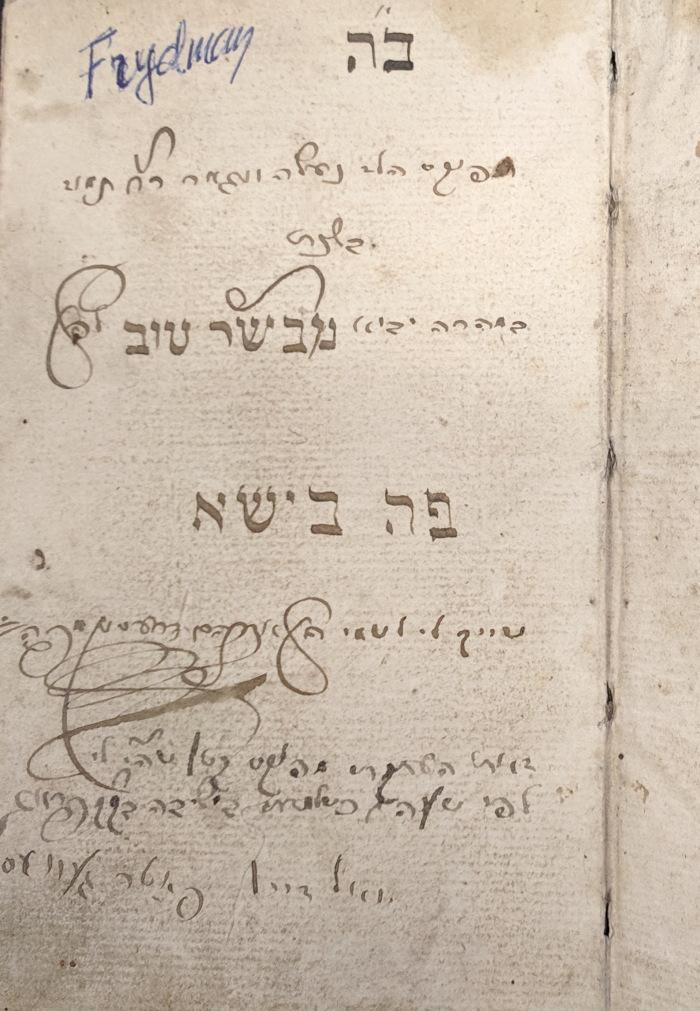

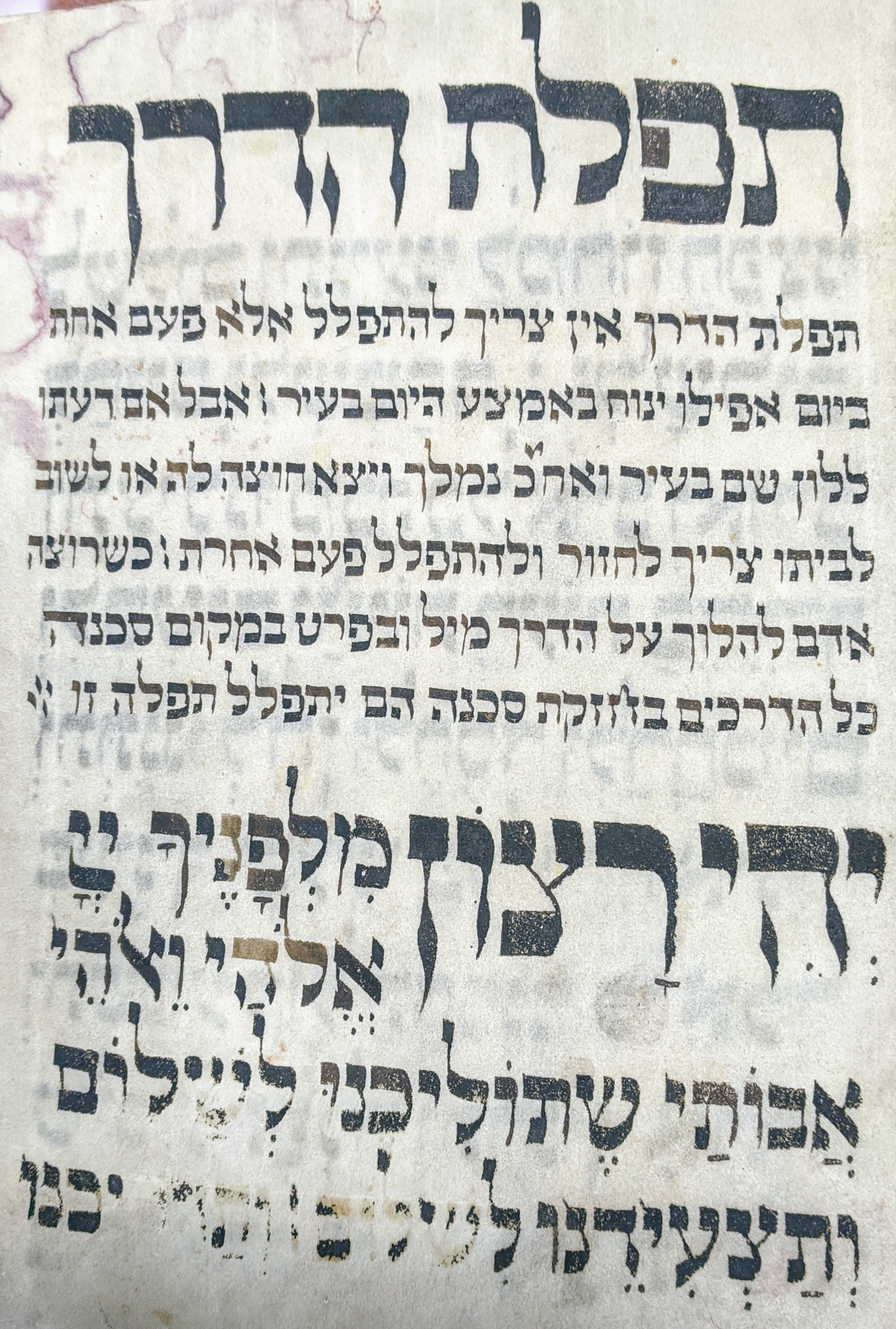

Now, we can finally turn back to our manuscript. The Wayfarer’s Prayer manuscript in the Karp Collection shows all signs of being an independent document copy of the prayer and is unlike other examples of the prayer of this era (it dates from the 16th or perhaps the early 17th century). This is visible, firstly, in the choice of script and layout of the manuscript, which closely resembles some of the fine printed books at the printing press of Gershom Kohen of Prague (d. 1544), whose style quickly grew in popularity and recognizability during the latter 16th century in Bohemia, Moravia, and eastern Germany.

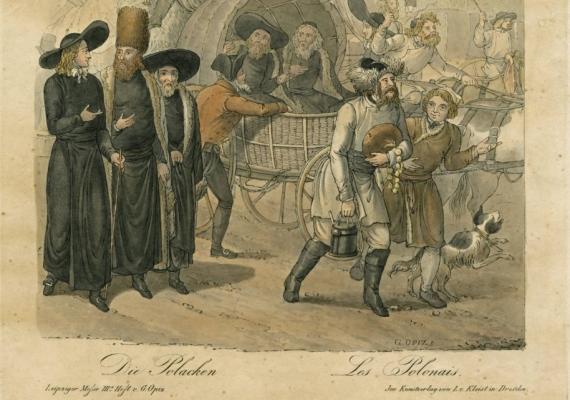

We can assume this to mean that a frequent traveler (likely a merchant) had this manuscript commissioned, based upon his choice of extraneous verses and short excerpts of halakhic instruction from the Arba’ah turim, the 13th–14th century comprehensive halakhic code of Ashkenazic custom.

Some of the verses that our merchant chose include the following (translation is mine):

“And Jacob traveled forth on his journey, and there encountered messengers of God (i.e. angels). And Jacob declared as he saw them, (ra’am) “this is the encampment of God!”, and he called the name of that place Mahanayim (encampments).” (Genesis 32:2-3)

“May God give perseverant strength to his people; may God then grant his people with peace.” (Psalms 29:11)

Following the commentary/instruction at the top of the folio, the Hebrew word occurring in the verse in Genesis (ra’am) contains a punctuation mark indicating that it is an abbreviation of Refa’el Uri’el Micha’el, the three archangels who are appointed to keep harm away. The significance of this is that, just as Jacob was able to visualize his guardian angels on the road and confidently travel the dangerous path to Paddan Aram, our anonymous traveler should also travel safely in the presence of the three archangels.

The manuscript further invokes another (lesser-known) protecting angel named Yuhakh; I wrote in the catalog summary of the manuscript that the identity of this angel is of questionable origin (some believe that its name is a four-letter acrostic derivation from a verse in the Psalms, while others believe that it is the name of the sword of God).

The prayer reads as follows (translation is mine), following instructions to repeat three times:

“Yuhakh, guard us! Yuhakh, spare us! Yuhakh, assist us!”

This prayer is followed by instructions to repeat the verse (Genesis 49:18), “To your salvation I await, O God,” again quoting Jacob – who, in the Biblical story, had just finished speaking his final words to his seventh son, Dan, by foretelling that (his tribe would become) “…vipers on the roads, biting the heels of horses, (which then) toss the rider backward (ibid., verse 17)” – meaning, that they would become highway bandits. This is likely why the verse is mentioned here, as our traveler is fervently praying that he shouldn’t meet robbers, thieves, pirates, and other dangers on the road. (Another surprising element to the repetition of this verse is that the words are repeated in a different order, which stems from an old custom meant to confuse and repel demons).

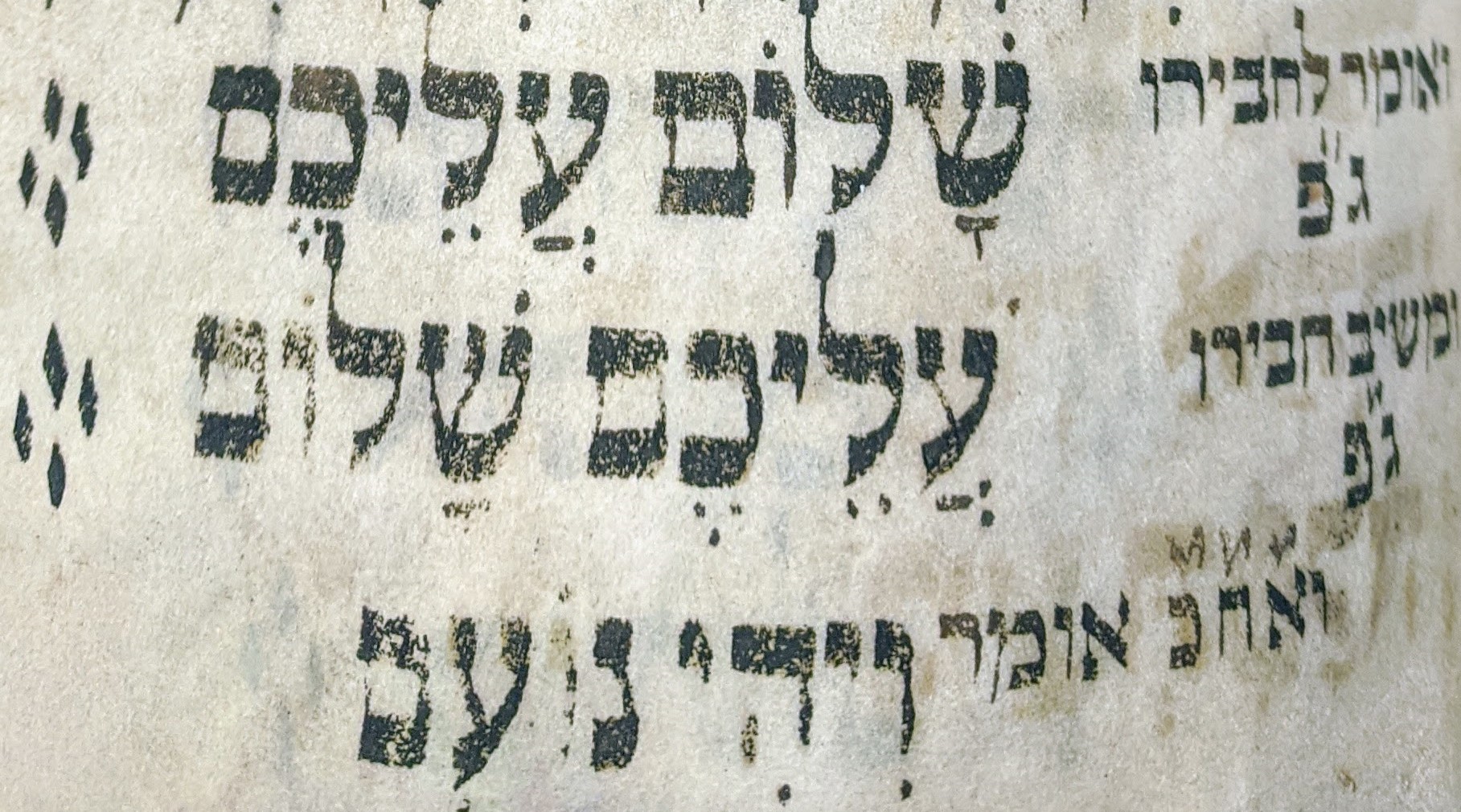

Another element which our traveler chose to add to his manuscript upon commissioning the scribe were the words “shalom alekhem (peace be unto you!),” used to greet fellow travelers, who would then respond, “alekhem shalom (and peace be unto you)!” I haven’t seen this custom included in any other manuscript or printed version of the Wayfarer’s Prayer, confirming the value of this rare item.

This is an abridged version of a blog post that appeared on Penn's Special Collections blog. Click here to read the original version.