Q&A: Katz Center Fellow Uri Erman on Jews in the British Opera in the 18th and 19th Centuries

Steven Weitzman speaks with fellow Uri Erman about the intersection of opera and the fraught experience of assimilation for 18th and 19th c. British Jews.

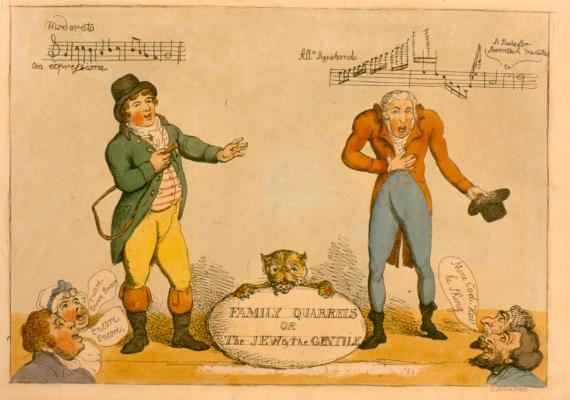

Family Quarrels, or The Jew and the Gentile, caricature ca. 1802, by Thomas Rowlandson depicting the singers Charles Incledon (left) and John Braham (right).

Steve Weitzman (SW): Uri, might you begin by telling us a bit about your larger project on opera in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and what led you to this interest?

Uri Erman (UE): Opera was a hotly debated issue in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Britain, perhaps one of the most prominent debates that engulfed the cultural scene of that era. On the one hand, opera was seen as a foreign imposition, a form of aural luxury imported from continental, Catholic Europe that catered mainly to the vitiated tastes of the nobility. On the other hand, there was a growing realization that opera was a marvelous artistic achievement and that there was a need to adapt it into the British cultural sphere. Handel’s biblical oratorios were one way of solving this tension: with their simpler vocal address, set to English texts, and within a devotional frame of reference, his oratorios were quickly canonized and became the defining feature of British musical identity.

However, this development also had a stifling effect, making it ever more challenging to offer “secular” forms of English-language operas. A mid-century theatrical piece clearly reflects the tension: “John Bull [the personification of Britain] was made to roar, not to sing.” This is the starting point for my project—the fact that singing became a central issue of identity in eighteenth-century Britain. My book project Made to Sing: Opera, Gender and National Identity in Britain, 1760–1830 (Oxford, forthcoming) focuses on the 1760s onward, and the attempts to break away from these confines and to offer British audiences a vision of themselves as a singing nation through the rise of English-language opera. And it was the singers who were placed at the center of this endeavor, while also bearing the brunt of the anti-operatic attacks.

SW: How do Jews fit into this larger story about opera?

UE: There were several Jews, men and women, who had successful singing careers at the time, and they played a prominent and surprising role in the cultural endeavor of English-language opera. For example, one of the chapters of my book focuses on attempts to refashion notions of masculinity in relation to singing. There was an effort to adopt high-pitched male singing—of castrati, but mainly of falsettists (what today we would call countertenors)—as a sign of male refinement and gentility. The most prominent singer in this cultural endeavor was a Jew named Myer Lyon. He was a “meshorer” (a harmonizer of the hazan’s melody) at the Ashkenazi synagogue, and his performances there drew large crowds of non-Jews, eventually allowing him to transition into the theatrical and operatic London stages. He Italianized his name to “Michael Leoni” but was widely recognized as a Jew throughout his successful career in the 1770s and 1780s.

This case fascinates me. Leoni’s falsetto was first recognized and appreciated in the synagogue, and then it was transferred to the theatrical stage to serve a distinctly forward-looking cultural agenda: that of “lyricizing” men. The connection here between Leoni’s minority identity and his ability to offer a different outlook on contemporary mores is quite striking. It places the Jew as a herald of new forms of sounding and expressing, and reveals the British public sphere as open to them, in fact activelty seeking them and their transforming effect. However, this position was also paradoxical: if the Jew was a herald of novelty, then this novelty could quite easily be denounced as somehow “Jewish.” Leoni and his falsetto singing suffered such attacks, tinged with anti-Jewish sentiments. It seems to me that, within cultural and artistic settings, Jews have often found themselves in such paradoxical positions.

SW: What is unique about these Jews’ engagement with the operatic medium, and how do you view this historical episode?

UE: One can see in this engagement just another avenue for Jews to interact with the majority society and seek advancement and socialization. It obviously relied on contingent circumstances, such as having a singing talent. But talent always demands cultivation and recognition. In this respect, this episode speaks of a unique social context: first, a majority culture that places great importance on merit and is liberal enough to celebrate merit when it is found. But more than that, the celebration of Jewish merit could serve key functions for the construction of British identity itself—in terms of its self-perception as an “enlightened” society, or, quite contrarily, in evangelical terms, finding in the Jewish soundscape hints for a fulfillment of a prefigured past.

Whatever the motivation, these Jewish singers were accorded a position of unprecedented cultural authority. Operatic singing is a powerful, bodily manifestation that places the listener “at the mercy” of the singer, while the singer himself exhibits his acculturation to the majority culture. This dynamic led to repeated breakdowns, moments where audiences could no longer uphold the implicit call for inclusivity. This was particularly palpable in the case of Handel’s oratorios, the very heart of Britain’s musical canon, that formed part of a widespread cultural endeavor to crown Britain as the modern-day chosen nation of God. The Jews’ performances in these works challenged this process of identification, as the figuration of Britain as ancient Israel now rested upon actual Jews. I have found fascinating reactions to such performances, where audience members are suddenly awakened to a perceived threat, as if the Jewish singer operates as a menacing duplicate that takes possession of their own music and, more importantly, of this music’s devotional function. So, there were definitely limits to the inclusive gesture and to how these Jewish singers were listened to.

SW: Your seminar presentation at the Katz Center focused on the renowned tenor John Braham (1774–1856), and there you argued that Jewishness was more central to his public and private life than earlier scholarship has recognised, albeit surfacing in complicated and contradictory ways. Your analysis was too rich to reduce to soundbites, but can you give our readers some sense of its argument?

UE: Braham (pictured to the right) is undoubtedly the most important figure in this group of Jewish singers. In fact, he was the most prominent British tenor of his day and dominated the musical stage for more than forty years. Upon hearing him for the first time, the famous German composer, Carl Maria von Weber, declared: “This is the greatest singer in Europe!” So we’re talking of a significant figure in both the history of Western music, and the history of Jews within it. This makes the question of Braham’s Jewish identity, and its function in his overall reception, very important. He was born John Abraham, but converted to Anglicanism at an early stage of his career and was careful to maintain a certain distance from his Jewish origins. Indeed, some scholars have argued that Braham’s Jewishness, particularly after a certain point in his career, played a relatively minor part in his reception.

his day and dominated the musical stage for more than forty years. Upon hearing him for the first time, the famous German composer, Carl Maria von Weber, declared: “This is the greatest singer in Europe!” So we’re talking of a significant figure in both the history of Western music, and the history of Jews within it. This makes the question of Braham’s Jewish identity, and its function in his overall reception, very important. He was born John Abraham, but converted to Anglicanism at an early stage of his career and was careful to maintain a certain distance from his Jewish origins. Indeed, some scholars have argued that Braham’s Jewishness, particularly after a certain point in his career, played a relatively minor part in his reception.

There is no denying his overall success and public standing, but I argue that the fact of his Jewish identity did not simply vanish from his auditors’ awarness but was instead ensconced as a potentiality deep within their psychology of prejudice. It could rise forcefully to the surface in certain contexts where Braham’s public persona was perceived as stepping out of bounds and making excessive claims to “Britishness.” This was often true for his performances of Handel, but it also rose to the surface in other contexts, such as his relations with members of the Royal family or his attempts to personify that most British of all personas: the seafaring, heroic sailor. Braham’s voice took him a long way, and allowed him to “conquer” his audiences, sometimes in spite of their prejudices; but this is the nature of prejudice—at the moment of its greatest frailty, it could rise again most forcefully.

SW: This is moving beyond the focus of your research, but I am curious: do you see ways in which the public persona of the singer in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Britain persists into contemporary times in the image of the singer today, either in Jewish or English-language contexts? Or how is the public figure of the singer different in the two different contexts?

UE: I think that the musical and cultural landscape today operates in quite different ways. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the operatic and theatrical spheres were very much centralized, with only a few “licensed” theaters in what was a highly regulated industry. Moreover, the periodical press in Britain, although relatively free and uncensored (compared to other parts of Europe), was also very partisan and often explicitly biased toward certain agendas. All this made for a challenging terrain for a singer—or any public performer—to navigate. In the case of the Jewish singers, one gets the sense of a combative public discourse conducted on their backs, imposed upon them, while they had minimal means to interject, limited as they were to their in-auditorium interactions with their audiences. Indeed, we have very little means of knowing exactly how they experienced these dynamics. I think that public performers today are much more liberated in this sense, with multiple ways not only of exploring their identity (including their religious and ethnic identity), but also of controlling its public manifestations. This is part of a wide transformation of the cultural arena, of what is often termed “celebrity culture,” with a derogative sneer. There is a lot to sneer at, but to my mind, this culture, and its championship of a wide array of complex, multifaceted public personas, has done wonders to our ability to explore our own selfhood.