Q&A: Katz Center Fellow Julia Watts Belser on the Talmud, Disability Studies, and Environmental Humanities

Steven Weitzman speaks with 2017–2018 fellow Julia Watts Belser about her research project "Nature, Sex, and Power in Rabbinic Tales of Noah and Sodom: Tracing the Afterlives of Cataclysm."

Steven P. Weitzman (SPW): Can you share with us what drew you to the study of the Talmud, intellectually and personally?

Julia Watts Belser (JWB): I came to Talmud quite unexpectedly. As someone whose intellectual passions run toward queer and feminist studies, whose political sensibilities have been shaped by the work of Adrienne Rich, Gloria Anzaldúa, and Audre Lorde, Talmud wasn’t exactly a natural fit. But I find Talmud a provocative medium through which to grapple with matters of power and violence, gender and the body. Working historically forces me to question carefully what I think I know. I’m always trying to check the assumptions I make about bodies, for example, to allow myself to be surprised by my sources. Most of all, I think, I was drawn to rabbinic stories—to the way they crack open hard questions and invite me to linger with the rabbis’ own uncertainties.

SPW: One of the goals of your scholarship and teaching is to bring disability culture into dialogue with Jewish tradition. How have you been pursuing that goal? Do you see that dialogue emerging within the field of Jewish studies more broadly? Where would someone in the field go if they wanted to learn more about disability studies?

JWB: In much of my work, I bring disability studies into conversation with rabbinic texts, examining how ancient Jewish texts understand mental and physical difference, how and why they stigmatize—and sometimes valorize—bodies that differ from their notion of the ideal form, as well as the cultural and political significance they attribute to disability. It’s an exciting time to be doing this work, because we’re in the midst of a real flourishing of disability studies in pre-modern history, literature, and religious studies. Disability studies and the Hebrew Bible is thriving—so I think that’s a great place for Jewish studies scholars to begin exploring the field.

SPW: Penn recently established a program in the environmental humanities, and thanks in no small part to your presence, this year has been a chance for the Katz Center to engage that kind of scholarship. I am thus moved to ask the following: What kind of responsibility does climate change impose on an academic field like Jewish studies? What can Jewish studies contribute to the environmental humanities?

JWB: Climate change is, in my view, one of the most pressing ethical issues of our time. I do feel an obligation to engage questions of climate, to ask myself how my sources might shed light on our present situation. I’m actually rather skeptical about whether the most commonly cited environmental passages in rabbinic literature are up to the task of forging an environmental ethic for the Anthropocene. I tend to look elsewhere, to stories about disaster, despair, and political violence. I find rabbinic stories useful for analyzing structural inequality that drives the call for environmental justice—or for illuminating what I call “climate silence,” the tendency to look away from crisis and catastrophe.

As for the responsibility that climate change imposes on Jewish Studies? I’d like to see us take a new look at academic practices—like routinely flying to conferences—that have a heavy environmental footprint. Might we find creative ways to limit those practices, to mitigate our harm? And when we do fly, can do more to make the carbon count?

SPW: One of the things I've learned this year is what a delightfully engaging and stirring teacher you are. What advice do you have for new or aspiring academics about how to develop as a teacher?

JWB: Thank you, Steve! I’ll share one paradigm shift that has sharpened my own practice as a teacher. Rather than organize my teaching around the facts I want to convey, I find it more fruitful to ask myself: What are the most important questions I want to raise for my students? How can I help them recognize what’s at stake? I spend a lot of time reading primary texts with my students—a built-in laboratory for inviting students to voice their opinions. My job, as I see it, is to help equip them with the critical tools to analyze, argue a point, and listen to each other. But I will say: Before I teach, I make sure to answer my own question about what’s at stake. I try to spend my time teaching things that matter, that I feel are worth sustained attention in these difficult days.

SPW: You've just had a new book come out, Rabbinic Tales of Destruction. The book presents a detailed analysis of how the Talmud describes the destruction of the Second Temple, a rich subject, but the book is about much more than that. Can you give us a sense of some of the questions or issues you are trying to address in this book beyond explicating the Talmud?

JWB: The Roman destruction of the Second Temple is one of the most discussed events in Jewish history! So why write another book on the subject? While many scholars have discussed the religious and political implications of Roman conquest, I focus particularly on how the destruction affected rabbinic understandings of gender, sexuality, and the body. I argue that the remembered risk and reality of sexual violence, enslavement, and war shaped rabbinic notions of body sovereignty, as well as their experience of masculinity and disability. The book also explores one of the things I found most surprising: Unlike many biblical narratives, the rabbinic stories I examine don’t use sexual violence as a metaphor to castigate women or Israel for sin—an unexpected and quite refreshing turn! Rather than focus on destruction as divine punishment for sin, some of these stories imagine God as suffering with victims of violence.

SPW: Can you give us a glimpse of what you've been up to this year at the Katz Center? And what's next for you?

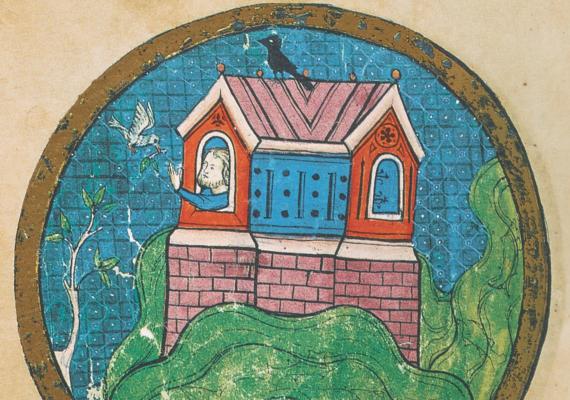

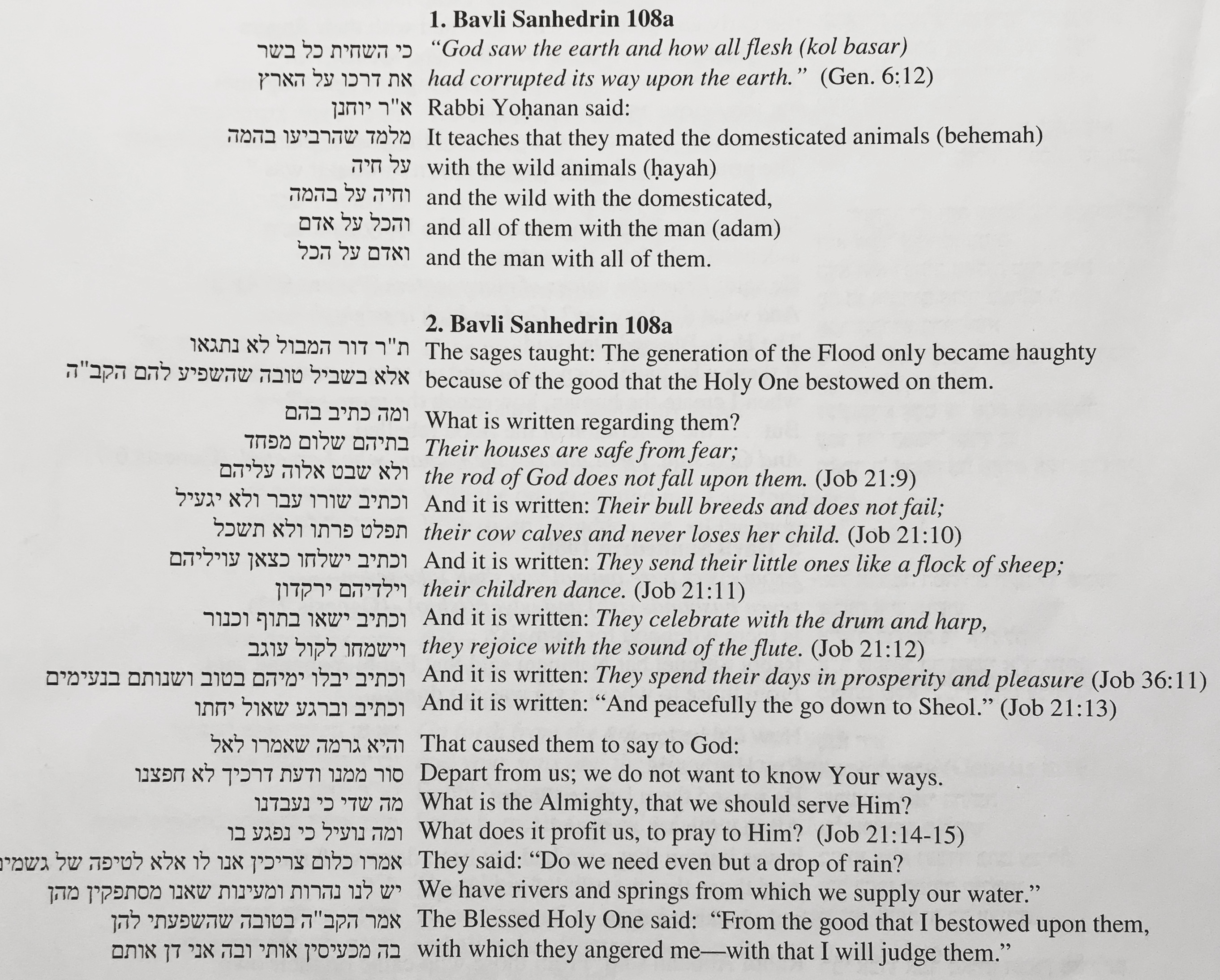

JWB: At the Katz Center this year, I’ve been working on rabbinic stories of Noah and Sodom, analyzing how the rabbis grapple with these two sites of cataclysm by fire and flood. I’ve been particularly interested in probing the way these tales highlight the connection between social violence and natural disaster—a nexus that’s also central to contemporary realities of environmental harm. As for my next project? I’ll be diving into a new book on disability and dissident bodies, examining how rabbinic narratives situate disability in relation to race and ethnic otherness, gender, and slavery.