Q&A: Katz Center fellow Jeremiah Lockwood on a surprising revival of classical cantorial music

Steve Weitzman speaks with 2023–24 fellow Jeremiah Lockwood about his life as a scholar and performer.

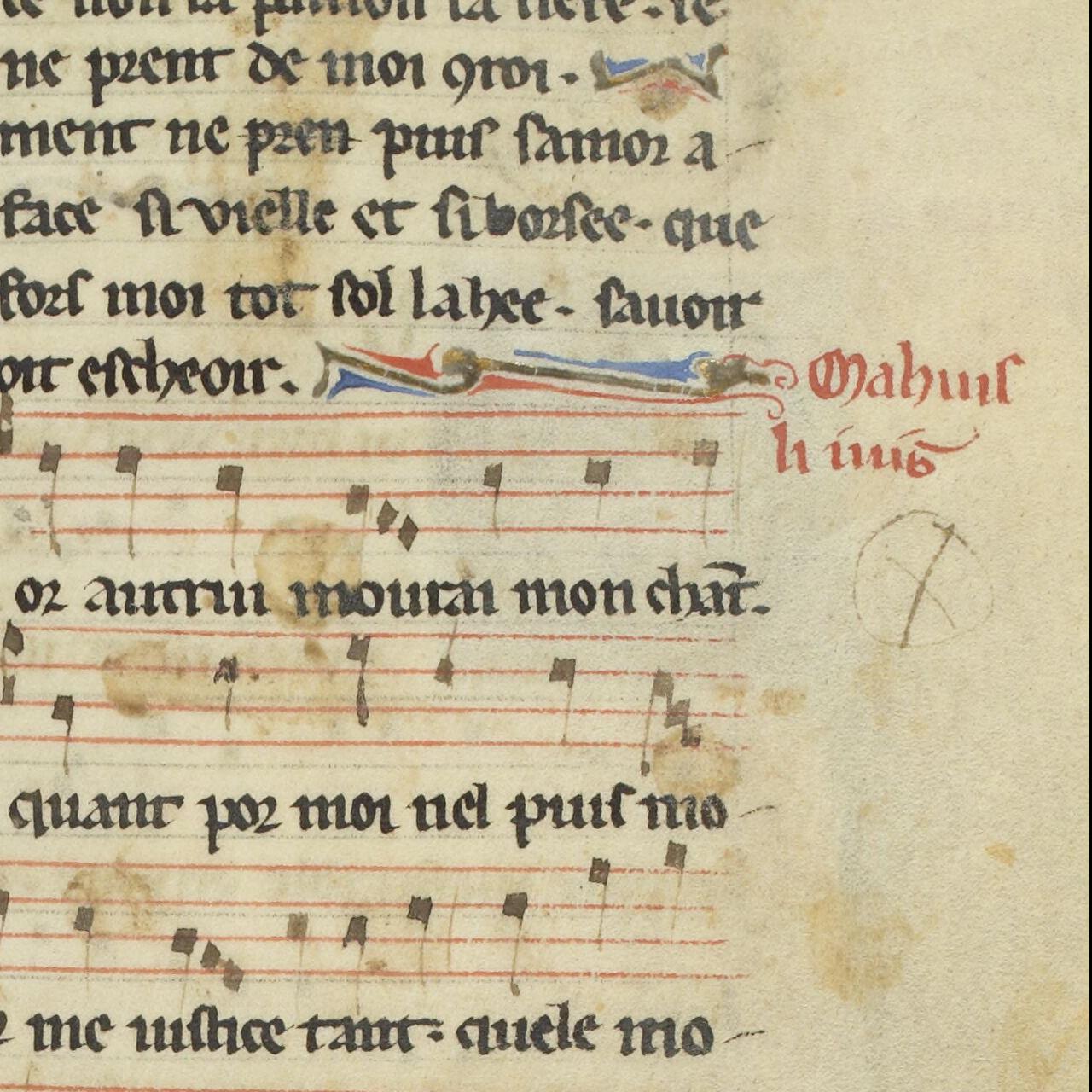

Detail from the cover of Jeremiah Lockwood’s monograph Golden Ages: Hasidic Singers and Cantorial Revival in the Digital Age (University of California Press, 2024)

Steve Weitzman (SW): Before we focus on your current research project, I wanted to note for our readers that you are just now publishing a new book. Could you share what it is about?

Jeremiah Lockwood (JL): My book, Golden Ages: Hasidic Singers and Cantorial Revival in the Digital Era, offers an account of the musical lives of singers in Brooklyn for whom an old style of Jewish sacred music, commonly referred to as khazones, is the basis of a nonconformist music scene. The scene fits jaggedly in the socially conservative and conformist Hasidic society, but also rejects the aesthetics of prayer in American Judaism writ large. I suggest that "cantorial revival," the musical practice of developing an artistic identity and Jewish ritual skill set based on recordings made in the early twentieth century gramophone era, is a countercultural movement that offers a critique of the institutional life of the Hasidic community and forwards a utopian vision of ritual spaces in which aesthetics and nonconforming identities are granted a position of authority.

SW: Although this book will be getting a lot of attention in the near future, you have come to the Katz Center to pursue a distinct research project also about cantors and cantorial music. Can you give us a glimpse of what this project is about?

JL: I spent my year at the Katz Center working on my second book project, tentatively titled Melody Like a Confession: A Cultural History of the Cantorial Gramophone Era. As the title suggests, the book will focus on topics related to the musical culture of cantors and the representation of cantors in transnational Yiddish literature and press. Across thematically arranged chapters, I argue that cantors were key participants in the emergence of modern Jewish intellectual life, alongside Yiddish modernist literature and Jewish political parties.

I am currently working on a chapter focused on the anxieties surrounding the mediatization and popularization of cantorial sound on records. Anxieties about the destructive effects of low art genres on sacred experience animated debates among cantors about what constituted appropriate ethical comportment and legitimate representation of the Jewish collective. In the cantorial scene the word hefker was used to describe this dynamic. Hefker is a talmudic term that signals property that has been abandoned. The phrase hefker khazones was forwarded by cantor and critic Elias Zaludkovsk in the 1920s to describe the ethical and aesthetic problems of cantors during the phonograph era. Zaludkovsky used the term hefker in its sense of sexual abandon to level accusations of immorality or sensual excess in the work of cantorial popular artists, but other connotations of hefker also inflect the meaning of this pregnant terminology. In contemporary literary contexts, hefker was used to describe the abandonment and desolation of Jewish life in Eastern Europe in the era of pogroms, especially in the heightened period of violence between the World Wars. In Yiddish experimental poetry, it sometimes described a modernist ethos of experimentation and boundary breaking. I explore four interweaving readings of the term hefker khazones: cantors abandoning their ethical commitments in favor of an eroticized commercialization and popularism; cantors abandoning traditional forms and functions of cantorial music in the pursuit of a set of modernist aesthetics; cantors serving a memorializing role in relationship to the abandonment of the Jews of Eastern Europe; and, finally, the abandonment of cantors by their communities in old age and how the image of the destitute and unloved old cantor inflects cantorial self-conceptions and collectivizing professionalization goals.

SW: In your fascinating seminar paper, a part of this project, you focused on early-twentieth–century female performers of cantorial music, artists who have been largely forgotten. In just a few words, can you give us a sense of who they were, and what you have learned about them?

JL: Taking advantage of the opportunities afforded by the new venues of cantorial performance on stage, radio, and on record, women singers began to emerge as popular performers of khazones starting by the 1910s. Khaznte, a Yiddish honorific for a cantor’s wife, was repurposed as a term for women who were themselves cantors. Creating a unique vocal set of practices that adapts a male vocal idiom to the woman’s voice, the khazntes reveal some of the gendered ambiguities of cantorial vocal styles. The male cantorial voice, with its affective practices that are imitative of the sound of crying and that revel in the falsetto upper range, seem to appropriate ambiguously gendered elements that are out of joint with normative western art music conceptions of male and female voice. The khazntes in turn reappropriated these sounds of Jewish sacred voice into a performance practice that foregrounds women’s aesthetic expertise, working on the fringes of Jewish institutional life but, at times, convening a mass Jewish listening public. While the work of the khazntes was effectively excluded by the cantorial professional associations and erased from most of the important anthologizing record releases of the post-WWII period, the memory of their achievement gives the lie to the normative claim that Jewish sacred vocal music is only male, proving that not only the future but also the past of Jewish sacred music was female.

SW: Through reading your work, I have come to more fully appreciate the role of the cantor as a mediator and agent of cultural and religious change. Do you see examples of cantors doing that kind of work in response to the many changes happening in Jewish life today?

JL: While I know there are many pulpit cantors who do important work advocating for social and cultural change, my research and musical advocacy focus on artists working in noninstitutional settings or on the fringes of institutional life. I am especially inspired by artists who use sounds and ideas from the cantorial past in the service of new artistic and political projects. A few examples include Judith Berkson, a cantor and experimental composer who is reclaiming the microtonal intonation of early cantorial artists as documented on gramophone records as the basis for a radical art music practice; Shahanna McKinney Baldon, a singer who is working on a performance project based on the life of Madame Goldye Steiner, an early-twentieth–century soprano who is the only known Black woman performer of khazones and whose work challenges conceptions of racial divisions and exclusions in Jewish American life; and Riki Rose, a formerly Hasidic woman who, among a variety of musical projects, interprets old cantorial records to frame a Hasidic woman’s vocal style that rejects gendered rules of self-expression that reflect social hierarchies in her birth community.

SW: You have come to the Katz Center to advance your work as a scholar, but you also create and perform music. Can you tell us a bit about yourself as a musician, and how that side of you relates to your scholarly side?

JL: This year while working at the Katz Center, I have continued to develop my multiple music and performance projects. In September, my band The Sway Machinery premiered a suite of songs, titled The Dream Past, that I composed based on bootleg recordings of cantorial High Holiday prayer services. Cantorial bootleg recordings are also the subject of a new article I wrote, forthcoming in the spring issue of Jewish Social Studies. Then this March, I took several of the cantors who I wrote about in my book on tour to Germany, where we did two concerts and premiered new arrangements I wrote for string quartet of classic cantorial recitatives. This year I have also been active with my blues duo Gordon Lockwood, with drummer Ricky Gordon, playing in clubs around New York.