Katz Center’s Becky Friedman on Jews and Jewishness in English Renaissance Drama

This blog post is part of a series focused on the research of fellows. In this special edition, Katz Center Director Steven Weitzman sits down with Becky Friedman, the Center’s communications coordinator, who recently defended her dissertation, “The Badge of All Our Tribe”: Contradictions of Jewish Representation on the English Renaissance Stage.

Steven P. Weitzman (SPW): Becky, first of all, I have to convey a huge congratulations on completing your doctorate. It is quite an accomplishment to have completed a dissertation while working full time at the Katz Center and living through a pandemic. I really have to salute you for your resilience, but even setting that part of the process aside, I have to add that it is a genuinely fascinating dissertation, and as someone who once thought about becoming a scholar of Shakespeare himself, I am envious that you get to work on such rich material.

To celebrate this moment, and to call your work to the attention of the Katz community, I wanted to do the kind of interview with you that I do with our fellows. Thank you for letting me pose a few questions.

For my first question, can you tell us a little about your dissertation? What is its focus, and what led you to this topic?

Becky S. Friedman (BSF): Thank you so much, both for your kind words and also for the opportunity to discuss my work!

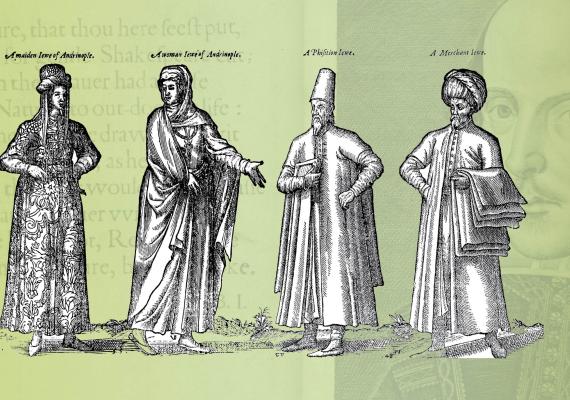

My research examines the representation of Jews and Jewishness in English Renaissance drama, with particular attention to the theatrical uses of gesture, mobility, and material elements—including costumes and props—to analyze the embodied performance of Jewishness and its multidimensional layers of signification. Additionally, it examines the language of Jewishness, including a close analysis of speech patterns, names, and vocal diversity that contribute to the heterogeneity of Jewish dramatic representations.

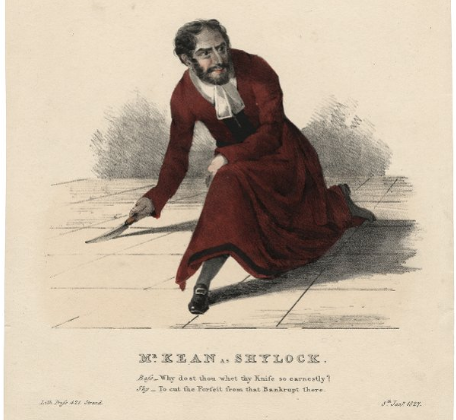

My interest in the topic began in my first year of graduate school, when I read an article by Emma Smith about the stage history of depicting Shylock with red hair. As a Jewish redhead myself, I was fascinated by this particular tradition. I began to explore the ways that Jews were incorporated on the stage. In the course of my dissertation research, I saw major differences in Jewish male and female characterization. These gendered divergences guided my focus towards English theatrical history’s production of Jewish characters who, on the one hand, typified villainy and a variety of diabolical proclivities, and on the other, embodied goodness and a host of Christ-like attributes.

SPW: The various plays you discuss were written in a period before Jews were allowed to return to England after their expulsion in 1290. Why were Jews so central in Renaissance-era English imaginations if there were no Jews permitted to live in England at the time?

BSF: England is the place where the ritual murder libel began and the site where European expulsion measures originated. The Jews’ story is thus inextricably linked with English history and the English imagination. By the time that Shakespeare emerged in the early modern period, Englishness had also been defined, in part, by its distinctions from Jewishness, and references to those (perceived) crucial differences naturally make their way into popular performance.

In addition, the Jews were not quite as absent during the expulsive period as we once thought. There is evidence of their presence across numerous London neighborhoods, meaning that English playwrights did not conjure Jews strictly from historical records or travel narratives. Even more, widespread knowledge of the Marrano lifestyle made the Jew a useful stage figure, naturally inclined for performing and inhabiting roles.

There was also an emerging English fascination with Jewish people and culture at that time as a result of the rise of Christian Hebraism, with Protestant translators of biblical works adapting Hebraica for English contexts. William Tyndale’s Bible (1530), for example, came from Hebrew rather than Latin, marking a meaningful shift in England’s nation-building project and in distinguishing itself from the Latin texts of the Catholic Church. The Jews played an essential role in this process, serving the interests of a culture that sought to replace them as the new Chosen People.

SPW: Many earlier scholars have commented on the negative caricature of Jews in English Renaissance drama, and the vengeful Shylock is the archetypical example. Your analysis aims for a more nuanced approach by attending to the “contradictions of Jewishness” enacted in drama from the period. Can you explain what you mean by that?

BSF: There is an impressive amount of scholarship examining the pejorative attributes of Shylock’s characterization, ranging from his animalistic qualities to his bloodthirst (which has even been theorized as a desire to impose circumcision on Antonio). But there are also crucial moments in The Merchant of Venice which undermine Shylock’s Jewish difference. The 3.1 “hath not a Jew eyes” speech, which many people may recall, captures this ambiguity well in its attention to the Jew’s humanity. In fact, there are many moments in English dramatic texts which reveal ambivalence about Jews, contradicting the enduring assumptions of comprehensive antipathy. My dissertation traces these moments, uncovering a fuller view of contemporary representations of Jews.

Recognizing the imaginative and interpretive potential of the Jewish stage figure offers us a more accurate picture of the complex attitudes towards Jews and Jewishness in the English Renaissance period. It also rectifies the Jews’ status; they are not just stock types signaling Otherness, insidiousness, or even comedy, but rather versatile characters suited to advance the imaginative, adaptive, and interpretive work of the theater. It is a thrilling phenomenon given the anti-Jewish backdrop of contemporary London.

SPW: Another fascinating aspect of your research is its attention to the physical dimensions of theater—how characters are dressed, for example, and the representation of architecture on the stage. Can you share an example of what you were able to learn by attending to the physical staging of these plays?

BSF: The theater had built-in mechanisms to fulfill specific functions. The trap-door, for example, was associated with hell and with evil more generally, and was used for the entrances and exits of ghosts in plays like Hamlet. When I first started examining the staging of dramas that involved Jewish characters, I wondered if the trap-door might have been employed to convey wickedness or transience. Plays that incorporated Jewish homes seemed particularly well-suited for the use of the trap-door apparatus given the Jews’ status as non-citizens in many European contexts. Situating the Jew below the platform of the stage could have been a no-brainer for all of these reasons. But Christopher Marlowe’s Jew of Malta (c. 1589), for example, reveals that Jewish housing is not relegated to marginal or inferior spaces at all. Stage directions, plot, and speeches disclose that Barabas’s home is in an elevated spot, and Maltese authorities even refer to it as a “goodly house.” Deferential as this staging may seem, it does not mean that the theater was seeking to project a dignified living arrangement onto the Jewish characters it portrayed. Rather, these depictions first embellished the Jews’ status as unduly high in order to justify their later depositioning. In all cases where a Jewish home is rendered in a contemporary context, the plots eventually enforce the need for displacement, dispossession, or destruction. Barabas’s house is requisitioned early on in Marlowe’s text, and converted to a nunnery in a tidy expression of supersessionism.

SPW: Since The Merchant of Venice is the most familiar play from this period, can I ask if you can share something you've discovered about the play that might cast its depiction of Shylock in a new light for our readers?

BSF: Most people are familiar with Shylock’s threat of taking a “pound of flesh” from Antonio, something that is often captured pictorially with a figure wielding an enormous blade. This type of image makes the danger of the knife the focal point when, in truth, Shylock himself would have represented the greater threat to Shakespeare’s audiences. The Jewish man’s body was a disturbing prospect for contemporary theatergoers because of wide-ranging discomfiting fictions that included unnatural blood loss through male menstruation. The ruinous myths of Jews poisoning wells and imbibing Christian blood added to that sense of hatred and repulsion. When picturing Jews of the English Renaissance stage, we must imagine ways that the actor incorporated these carnal associations while also relaying the subaltern status of the contemporary Jew. Hunched shoulders, a ducked head, eyes leering mischievously, grasping hands—this embodied performativity was as much a part of Shylock’s appearance as his knife prop.

All of this, of course, is in stark contrast with the beauty and desirability of Shylock’s daughter, Jessica, who elopes with a Christian man. Their divergent presentations encapsulate the contradictions of contemporary Jewish stage representation, which both insists on and denies the unappealing and ineluctable difference of Jewishness.

SPW: Finally, I want to ask a practical-professional question. A lot of talented early career scholars are having to consider professional roles outside the conventional tenure track. Do you have any advice for such scholars about how to sustain your intellectual/scholarly life in a role where you don't have much time to devote to your own research?

BSF: Doing research while maintaining a full-time job requires a lot of strategy and discipline. Establishing a strict writing schedule—and sticking to it!—was essential for me. Often, I’d work a full day at the Katz Center, take a break after work, and then begin writing/revising around 8pm, working until the early morning hours to reach my daily word count. Combined with many consecutive weekends which I dubbed personal “writing retreats,” the regimen was the reason that I was able to meet my research goals. I believe that there is no replacement for dedicated time to focus on research, so my advice is to ensure that every day, or every workday, has a fixed time set aside for scholarly tasks. Developing a plan to use that time efficiently is even better.