Jewish Affordable Housing Projects in Late Tsarist Russia: Urban Housing, Public Health, and Communal Responsibility

Katz Center fellow Cecile Kuznitz explores the enduring connections among urban design, public health, and economics.

As New York City became the epicenter of the Coronavirus outbreak, observers noted that cities have long been viewed as bastions of disease. In particular, as the industrial revolution led to rapid urbanization in the nineteenth century reformers sought ways to mitigate the public health problems created by overcrowded living conditions and lack of sanitation. Among the questions they asked: how could urban housing for the working class be improved and who was responsible for improving it?

Jewish philanthropists in the cities of Warsaw and Vilna addressed these questions by constructing apartment complexes that were among the most modern and innovative in the Tsarist Empire. In 1897 the Polish Jewish banker Hippolit Wawelberg created the Foundation for Inexpensive Housing to erect a set of three apartment blocks in Warsaw. This inspired the Jewish Colonization Association, a charitable organization headquartered in London and dedicated to aiding Russian Jews, to construct two similar structures in Vilna. The foundation also built a second development in Warsaw in 1927. Taken together these projects housed about 3000 residents, primarily artisans, factory workers, small merchants, and their families.

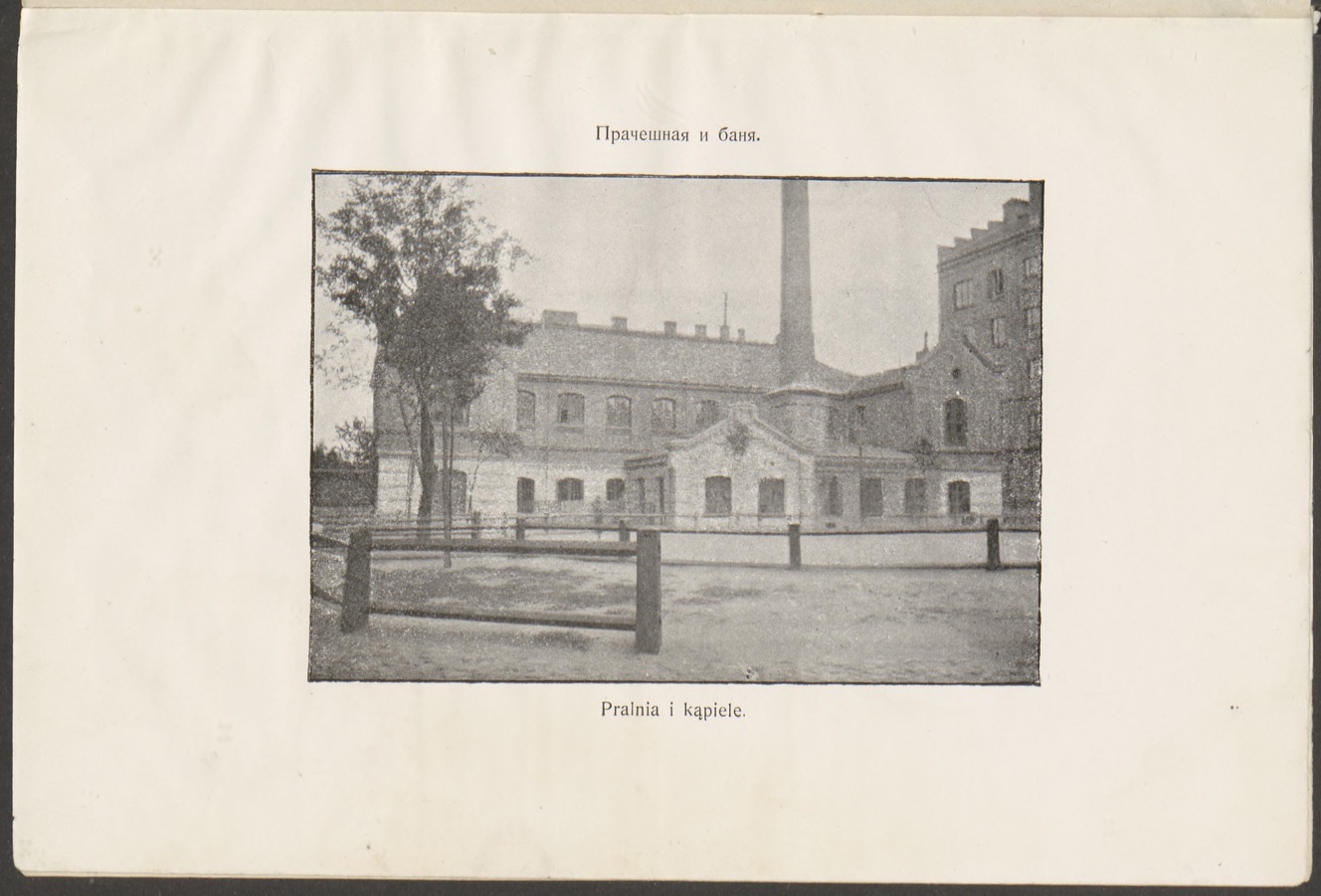

All of the buildings were located on the urban outskirts surrounded by gardens and open land, creating a green and healthy environment. Density within apartments was limited, with boarders and home manufacturing prohibited to further prevent overcrowding. Sanitary facilities included faucets, toilets, and garbage chutes, all rare amenities in working class housing at the turn of the century. Tenants were required to abide by regulations on cleanliness and to be vaccinated against smallpox. Each complex also featured a children’s day care, medical clinic, bathhouse, and laundry – and isolation rooms for those who might contract an infectious disease.

While these measures were designed to promote public health, residents’ social and cultural needs were met by reading rooms, lecture series, and “decent entertainment” such as dance evenings. These initiatives were in keeping with many reformers’ view of the connection among education, moral health, and physical wellbeing. In addition, Wawelberg believed that daily interactions among residents of different backgrounds would promote tolerance, so he mandated that the apartments be occupied by Jewish and Christian Poles in equal number.

Yet despite careful planning and expert advice, density rose over the intended level as large families crowded into the one room apartments. The projects’ initiators intended them to return a modest profit that would be reinvested in the buildings’ upkeep. Construction and maintenance costs were higher than anticipated, however, limiting profits and driving up rents. These high expenses eventually led the JCA to turn over control of the Vilna complex to the kehillah, the democratically elected representative body of Vilna Jewry, in 1933. The goal of diversity also proved elusive: Jews were reluctant to move to the relatively remote Warsaw buildings and hence their residents were overwhelmingly Christian, while the great majority of tenants in Vilna was Jewish. Nevertheless, the buildings did provide thousands of working class families with relatively affordable, modern housing in a healthful environment – and all continue to serve this function today.

The issues raised by these apartment complexes echo in contemporary discussions of the relationship among urban design, public health, and economics. As a recent New York Times article and exhibit at the Skyscraper Museum point out, and as the sponsors of these buildings discovered, urban density results both from choices about housing design and the socioeconomic factors that shape how individual homes are used. We have also seen how cultural factors have made certain groups more susceptible to the virus’s impact, while de facto segregation along ethnic and racial lines has shaped the geography of its toll on American cities.

The construction projects in late Tsarist Russia were initiated as acts of private philanthropy but one became a kind of public housing, as Vilna Jewry recognized a communal responsibility to provide shelter for its neediest members. As the pandemic continues we must ask ourselves who will take responsibility for addressing its health and economic impacts, and who will ensure the future wellbeing of American cities and their residents.

This piece originally appeared as a part of a series on the Bard College website. The source of the images is J. Brunner and K. Szokalski, Instytucya Tanich Mieszkań imienia Hipolita i Ludwiki małż. Wawelberg (Warsaw: Drukarnia Fr. Karpińskiego, [1903?]).