French Jewish Studies

What is happening in French Jewish studies? A snapshot

Engravings from Le Vrai Patineur (The True Skater) written by Jean Garcin (1813)

In recent issues, JQR has run forums dedicated to the state of Jewish studies seen through a regional lens, each with a unique organizing framework: see, for example, those on Eastern Europe (JQR 112.2) and Latin America (JQR 111.4). Turning to France, we invited a cohort of innovative scholars—Lisa Leff, Jay Berkovitz, Sylvie Anne Goldberg, Perrine Simon-Nahum, Ethan Katz, Aomar Boum, Richard I. Cohen, Samuel Sami Everett, Jordan R. Katz, and Sara Lipton—to contribute snapshots of Jewish-French history. We asked each to focus on a single artifact, choosing a fragment or document to puzzle over, marvel at, or situate in Jewish history as it has unfolded in the Francophone world.

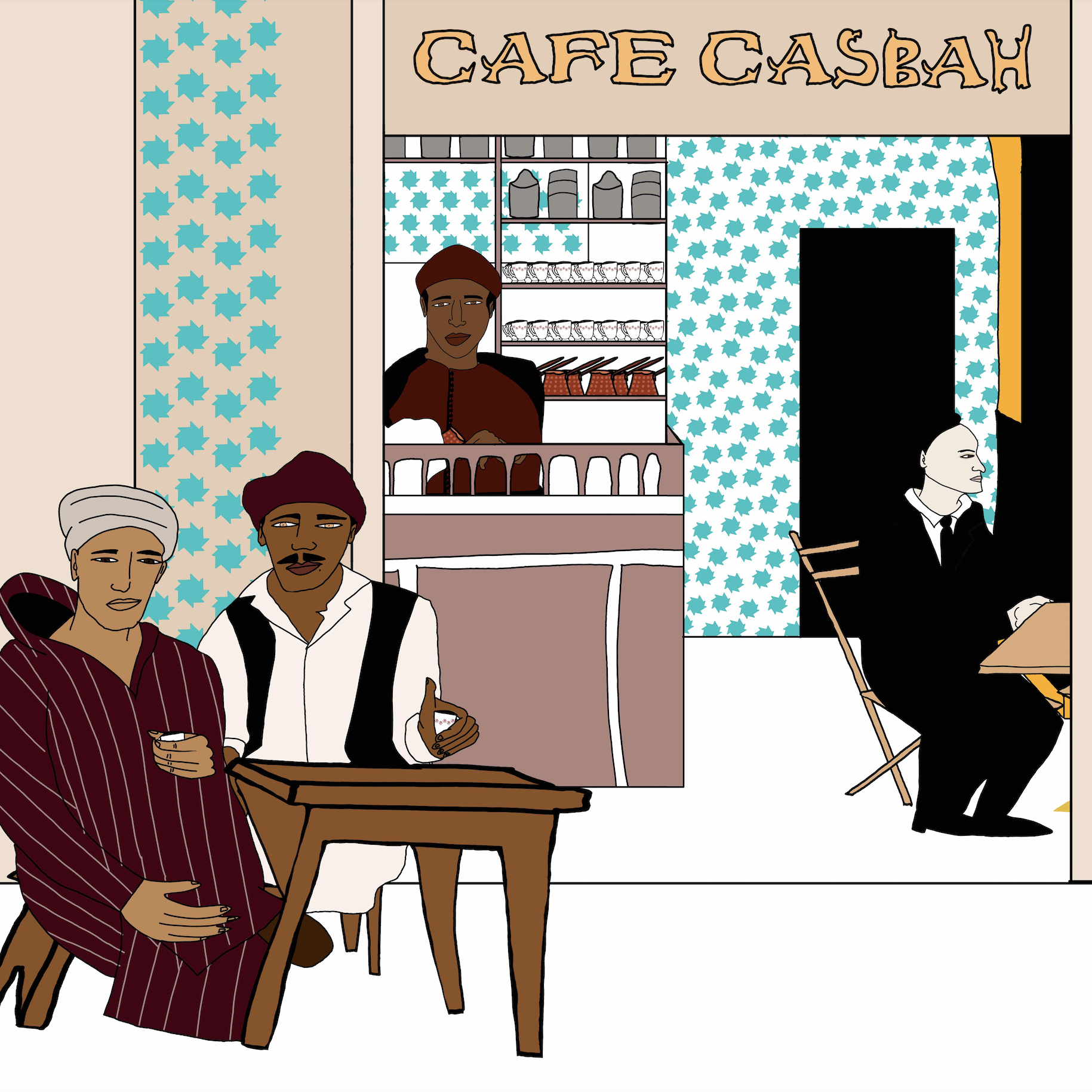

The results are wildly varied, moving from twelfth-century St. Denis to present-day Casablanca, and the essays are as jaunty as they are challenging and insightful. The materials invoked cover a range of media from administrative notes to travel posters, and include letters, animation, music, photographs, stolen documents, tombstones, and newspapers. In this case, a state—here, France defined broadly—turns out to be a rather less than useful frame for tracing a field over the longue durée, especially when telling Jewish history. Not only do the contributors to the forum themselves dwell in a global age, but the past is rife with blurred boundaries due to the changing regimes under which Jews lived in any region. The “region” itself has been in constant flux—extended and retracted by war and colonialism (and the stain they leave behind). Add to this constant Jewish mobility, multilingualism, and internationalism, and you get permeability rather than fixity. In fact, as the essays make clear, even using the French language as a criterion of selection is insufficient for the “France” defined and deconstructed by our authors.

Despite all that, the forum’s collection of essays shows its quixotic framing to have been a revealing catalyst. In his recent documentary history of French Jews since the late eighteenth century, Mathias Dreyfuss asks if and how French Jewish history fell “hors du récit national” (Mathias Dreyfuss, Aux sources juives de l’histoire de France [Paris, 2021], 19). These are questions to which our forum implicitly replies; even in the smallest fragments and snapshots that animate our authors, we discover a set of lively tales that, though largely unseen, are woven deep in and around the national narrative, changing it by their presence.

Together, the essays present a pointillist picture of Jews as seen by themselves and others. In nearly all cases, the Jewish subjects of whom we catch glimpses are teetering, often unstably, usually productively, between worlds. It is impossible to draw clear lines separating rhetorical from historical Jew, citizen from alien, and this is as true from the point of view of the Jewish gaze as it is for those observing from without.