Q&A: Katz Center Fellow Marek Tuszewicki on Folk Medicine in Eastern Europe

Q&A: Katz Center fellow Marek Tuszewicki on the knowledge and practice of healthcare as a pastiche of a different sources and authorities in the Ashkenazi communities of Eastern Europe

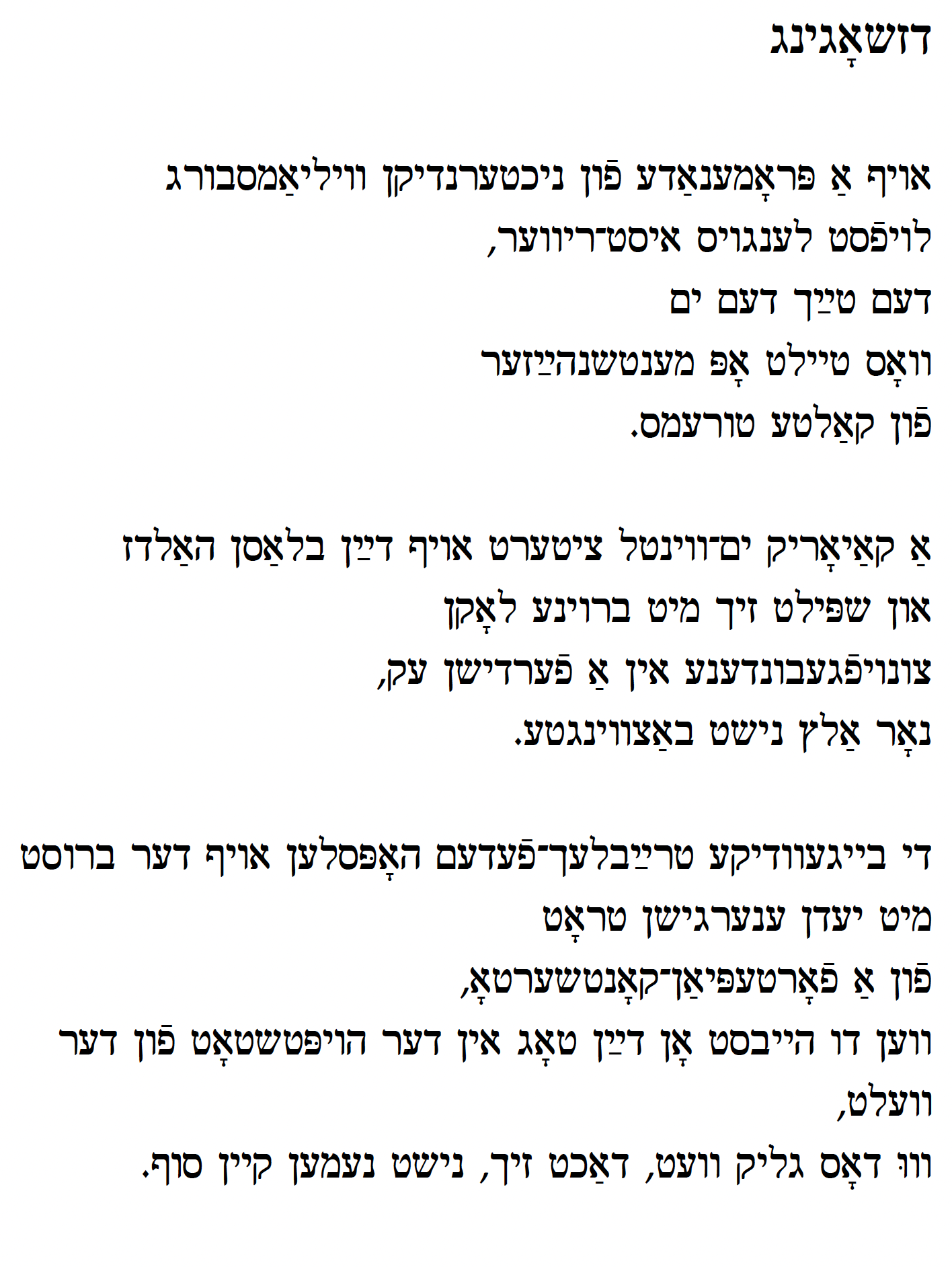

Detail from the cover of Marek Tuszewicki, A Frog Under the Tongue: Jewish Folk Medicine in Eastern Europe

Natalie Dohrmann (NBD): Marek, tell us a bit about your scholarly interests, what drew you to them, and what especially excites you about them personally and/or intellectually.

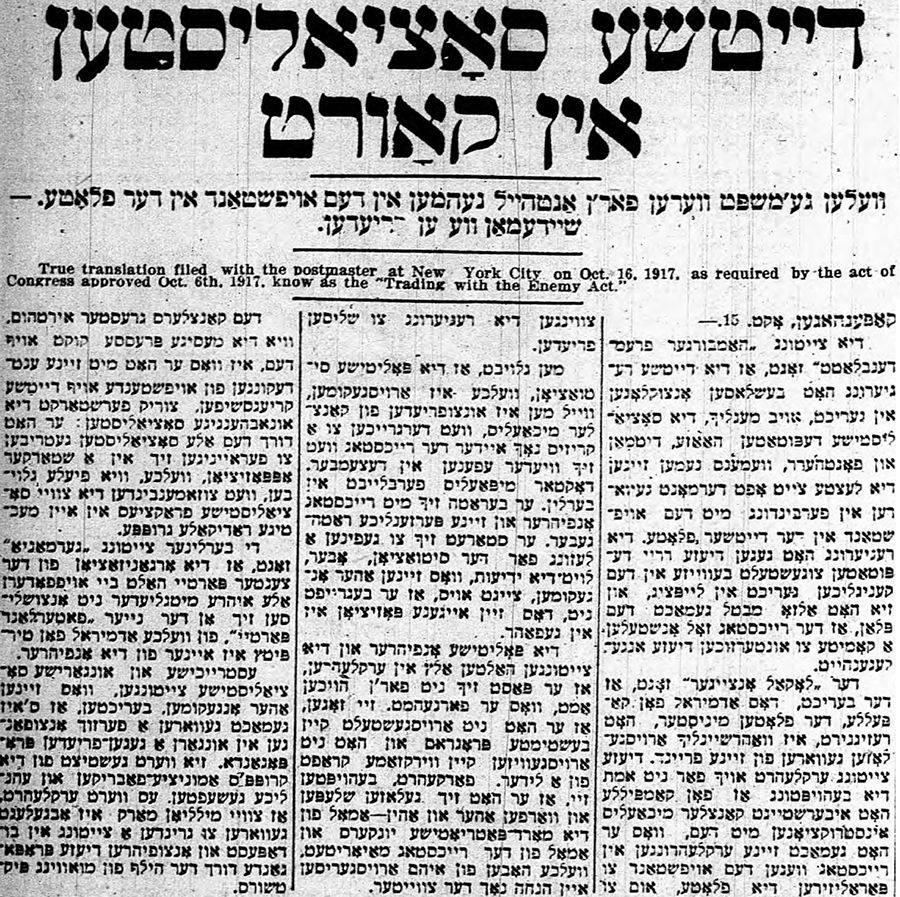

Marek Tuszewicki (MT): My interest in the culture of Eastern Ashkenaz began when I first encountered the popular hagiographies of Hasidic leaders published in Hebrew and Yiddish. As I studied the profiles of figures such as R. Chaim Halberstam of Sandz or R. Menachem Mendel Morgenstern of Kotsk, my attention naturally turned to the role of healers ascribed to them by tradition. However, even more than the miracles or the antidemonic rituals, I was interested in how Jewish religious leaders in Eastern Europe negotiated their place between ancient and modern medical cultures. This interest intensified after I discovered a number of publications on various medical topics printed in Hasidic circles in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Sometimes these were typical segulot u-refu’ot (books of charms and remedies) literature; other times they were collections of customs and editions of important ethical works enriched with appendices of health advice. In this period, the need to provide readers with practical information on medical treatment is evident, even among authors representing very traditionalist circles of the Jewish population. I was particularly impressed by the variety of advice. Some advice was heavily steeped in the kabbalistic tradition, including the use of amulets. Other pieces of advice faithfully reproduced practices I was familiar with from ethnographic documentation of the Slavs or adapted magical formulas directly from the surrounding languages. And perhaps the most fascinating entries took the form of meticulously transcribed recipes using Latin pharmaceutical terminology. And just as the former were usually accompanied by the names of famous rabbis and tzaddikim, the latter were sometimes supplemented by the names of professors of medicine from Vienna or Berlin.

I began to delve deeper into the beliefs, practices, and customs related to health, which I also came across while reading other sources. In addition to folklore collections, these were primarily first-person documents, both printed memoirs and manuscripts of various types, written down by Eastern European Jews for their own use. Relatively quickly, I realized that from these sources a picture emerged of the struggle of several fairly consistent, complementary medical systems. The first was based on oral and written traditions, including the rabbinic literature of past centuries, but was primarily rooted in the medical views of the Greco-Roman world. The second, on the other hand, had a modern dimension, its representatives being learned biologists, chemists, and finally doctors who, in the nineteenth century, tried to sensitize people in Europe to the need for a new attitude toward health—an attitude resulting from following the rules of science, including the strict interpretation of modern hygiene. From such fascinating material, a book was destined to emerge.

NBD: Your book A Frog Under the Tongue: Jewish Folk Medicine in Eastern Europe (2021) is a masterful survey of Jewish thought and practice concerning health and medicine in eastern Ashkenaz seen from the bottom up. The variety of evidence you consult is remarkable. Can you talk a bit about some of the strategies you use to get through the printed word to access lived experience and popular ideas?

MT: The sources I have had the opportunity to work with are surrounded by many misunderstandings. This is partly due to the limited knowledge most have today of older medical theories and partly due to the very terse way in which the medical manuals or manuscripts used in private homes were written. These sources are also burdened with the odium of harmfulness that was attributed to them during the period of modern medicine's struggle for supremacy in Western medical culture. The criticism of the biomedical authorities had its reasons. Even if the alternative they proposed is not able to treat many diseases, it has achieved numerous successes, significantly prolonged human life, improved its quality, freed us from the fear of death in childbirth or epidemics. However, when we look at historical sources through the modern lens, we tend to overlook the great web of interdependencies that arise from past views on health and how to help the sick. This is why it was so important for me to take a bottom-up perspective, as close to the people as possible.

However, this was only the first step. The diverse nature of remedies used in Eastern Europe in the nineteenth century made it necessary to apply a different methodology for each category. The understanding of medicines of natural provenance, based on mineral, plant, and animal components, required an extended knowledge of humoral pathology. The medicine of the Greco-Roman world, like the entire cultural heritage of the Mediterranean region, was rediscovered by Europe during the Renaissance. At the same time, around the turn of the sixteenth century, Krakow became an increasingly important place in Europe as the capital of the emerging Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The political elites of this state embraced the heritage of antiquity and, as a result, medical authorities such as Hippocrates, Galen, and Avicenna became a part of the local culture. This legacy was further reinforced by the economic collapse of the seventeenth century and the gradual slide of Eastern Europe into cultural backwardness. As a result, it was not until the beginning of the nineteenth century that the theory of humors was removed from the curricula of the medical faculties of Polish and Lithuanian universities. Is it any wonder that the views of ancient genealogy were still alive in the local population—Christians and Jews alike?

The study of folk medicine from a grassroots perspective also enabled a better understanding of the place of remedies based on kabbalistic manipulations and healing magic within folk practices. In the case of the Jews, this involved both their own magical tradition, which linked the various centers of the diaspora and the center of Jewish culture in the land of Israel, but also local magic: German, Slavic, perhaps Tatar. With such magical means, it is not enough to know their genealogy, because this says relatively little about their symbolic connections, their logic, or their imaginary potency. This is where anthropological studies help, adding explanations to the historical dimensions of such phenomena as the “evil eye” that relate to human nature, to the way a medical worldview is constructed, and so on. This anthropological perspective naturally compares different cultures, which soon appear much less different than they seem.

NBD: Your next project shifts your gaze to questions of health in the shtetl at the fin de siècle. How does this location and framing open new avenues in your research?

MT: While working on the previous book, I was particularly interested in the individual choices of sick people (or their relatives) who, in the period of struggle between traditional and modern culture, navigated very consciously the complex medical market. I was interested in the position of the trained doctors, but also of feldshers (formerly known as barber-surgeons), small-town specialists in natural healing (e.g., mohelim) or healing magic (e.g. opshprekherkes of the evil eye). However, I have devoted relatively little attention to the question of institutions dedicated to the care of the sick. Such institutions underwent profound changes in the nineteenth century, which also reflected the medical worldview of ordinary people.

Therefore, my next project will approach this particular topic from the perspective of a small urban center. In towns that were only marginally affected by the industrial revolution, it was difficult to establish a hospital, let alone a Jewish one. Meanwhile, over the course of the nineteenth century, and especially toward the end of this period, there was a real flourishing of Jewish institutions that cared for the sick. Initially, they arose from traditional, religiously motivated charity and were aimed at poor members of the community. However, with the transformation of religious confraternities into registered associations and the adoption of modern medical and hygienic standards—which were demanded of the associations by the non-Jewish authorities—the quality of the services also increased. Associations that organized night vigils by the sick or ran homes for the elderly acquired the status of philanthropic institutions that not only thought of day-to-day charity but also pursued a long-term health policy. Sometimes the activists, who came from very conservative and Hasidic circles, were involved in these changes, which seems to contradict the generally accepted clichés.

NBD: How does being part of a residential fellowship impact your scholarship?

MT: Arriving in Philadelphia has, above all, enabled me to turn my attention to writing. It may sound trivial, but the opportunity to devote myself exclusively to one project is a great benefit of the residential fellowship. With so much freedom in terms of time management and support that can hardly be overestimated, it is much easier to compose an original work. My project has benefited greatly from constant access to the resources of the University of Pennsylvania library. This is particularly important now as I develop the concept for a future book and prepare a chapter that requires an engagement with the extensive historical literature. The progress I have already achieved encourages me to broaden the scope of my archival inquiries, and I will certainly take advantage of Philadelphia's convenient location to visit several historical archives in neighboring cities.

It is also great that we do not have to wait until our scholarly endeavors are published in print to assess their impact on the field. The seminars held each week at the Katz Center are an excellent opportunity to discuss our hypotheses with colleagues who are at a similar stage of research, as well as with experts from various fields in the humanities and social sciences. Although this year fellows are separated by epochs, we are addressing very similar problems. In the context of medical traditions, the voice of historians, whether of ancient, medieval or modern times, is equally inspiring.

NBD: I saw online that you are a poet, do you want to share with us some thoughts on that part of yourself and/or one of your poems?

MT: The story of my difficult relationship with poetry is not much different. As a student, I tried my hand at translating Yiddish and Hebrew prose and also began writing short texts myself, mainly as a hobby. At that time, the Yiddish magazine Dos Yidishe Vort was published in Warsaw by Kobi Weitzner, the unforgettable klal-tuer and playwright. It was his encouragement that convinced me to systematically develop my writing skills. Much later, I came into contact with a group of contemporary Yiddish poets, Prof. Dov Ber Kerler, Velvl Chernin and Mikhoel Felsenbaum, with whose help I published my poetic debut, first in the press and later in a volume of my own. Writing in Yiddish actually helps me to keep my imagination in check and at the same time allows me to deal more boldly with my longings, fears, and fascinations. I write about what I experience or see, drawing from the world that surrounds me, but always through the filter of a beating heart.

Jogging

Af a promenade fun nikhterndikn Viliamsburg

loyfst lengoys Ist-River,

dem taykh dem yam

vos teylt op mentshnhayzer

fun kalte turems.

A kayorik yam-vintl tsitert af dayn blasn haldz

un shpilt zikh mit broyne lokn

tsunoyfgebundene in a ferdishn ek,

nor alts nisht batsvingte.

Di beygevdike trayblekh-fedem hopslen af dayn brust

mit yedn energishn trot

fun a fortepian-kontsherto,

ven du heybst on dayn tog in der hoyptshtot fun der velt,

vu dos glik vet, dakht zikh, nisht nemen keyn sof.