Messianism, Manuscripts, and Music

Sabbatian songs were performed publicly for the first time in a concert presented by the Katz Center, the Mandel Scholion Research Center, and the Weitzman Musuem.

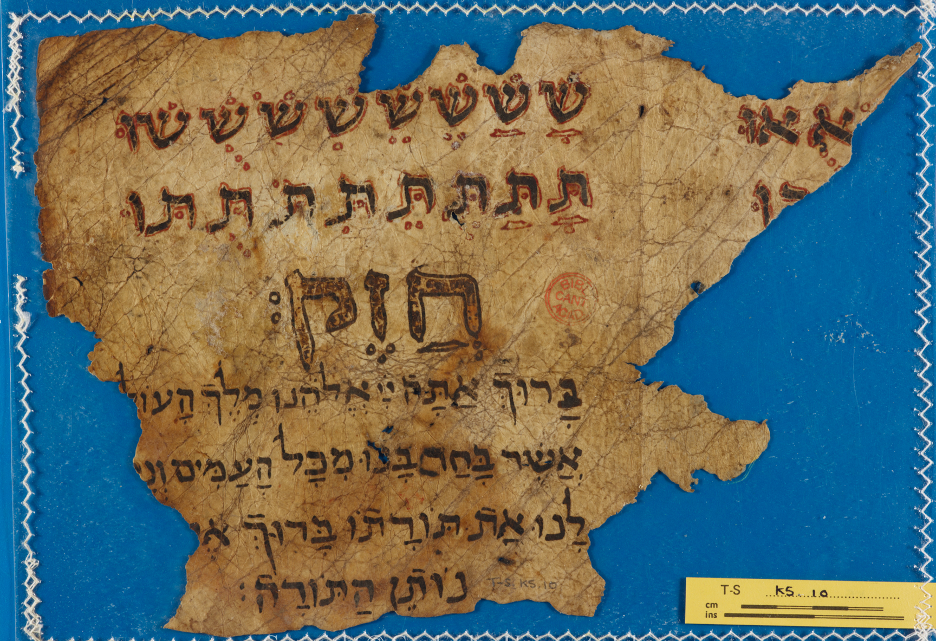

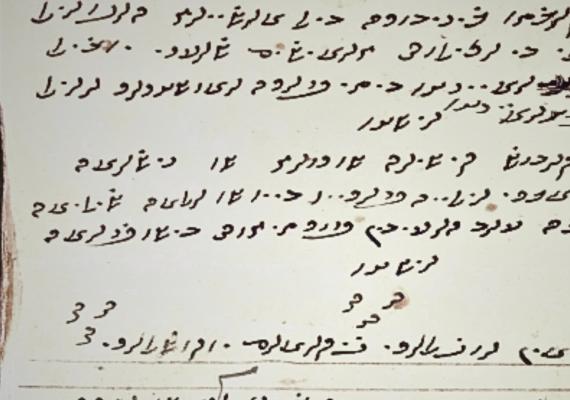

Manuscript of the Sabbatian hymn “Goalenu Amira” (based on the melody of the Turkish song “Yemenimin uçları çıkamam yokuşları”). Harvard-Houghton Ms. 80, song 812.

Current fellow Hadar Feldman Samet has been working for years on a trove of particularly intriguing but difficult manuscripts. She is decoding the dense, multilingual songs of the sect of Sabbatians that maintained secretive religious beliefs and practices for centuries. Based on indicators in the handwritten texts of hundreds of hymns, full of kabbalistic and messianic symbols and abbreviations, she has managed to reconstruct the tunes that some were sung to.

Recently, some of those songs were performed for the first time in public, outside of their original liturgical context, in a concert and talk that showcased the music of the Ottoman world in which the Sabbatians developed their faith and composed their hymns. Combining performance and discussion, the event wove together the interconnected musical traditions of Jews, Muslims, Christians, as well several heterodox groups among them, each tradition shaped by centuries of coexistence. The music was expertly performed before a packed house by Dünya Ensemble, headed by Grammy-nominated artist and scholar Mehmet Ali Sanlıkol, who also provided commentary. Feldman Samet illuminated the historical context.

The Katz Center was gratified to partner with our colleagues in Israel at the Mandel Scholion Research Center at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem to put on the event, recognizing that both institutions have supported Feldman Samet’s ongoing work on the Sabbatian hymns. We also appreciate the partnership of the Weitzman Museum of American Jewish History, which shares a commitment to presenting diverse forms of Jewish culture.

To learn more about these songs and the sounds of the Ottoman world that shaped them, stay tuned for the release of the video of this program.

In the meantime, you can read some of Feldman Samet’s work on the subject in JQR. Below is an excerpt of her 2019 article on the Ottoman songs referenced in the manuscripts of the Sabbatian believers.

* * *

THIS PAPER OFFERS a new perspective on the mystical writings generated by the “Ma’aminim” (the faithful). The Ma’aminim, a group commonly known by their derogatory Turkish name Dönme (turncoats), were descendants of Sephardic Jews who interpreted the conversion to Islam of their messiah—Shabbetai Tsevi—as a necessary step toward redemption, forming a secret community of converts in his wake. The Ma’aminim lived in Ottoman Salonica, one of the most important port cities of the Ottoman Empire, the largest center of Sephardic Jews, and home to various Muslim and Christian communities. The Ma’aminim were formally Muslim and part of Ottoman Islamic society, yet they maintained cryptic associations and practiced in secret a unique messianic religion. As a result of this secrecy, their intellectual, social, and spiritual world has long been terra incognita to outsiders.

The internal communal writings of the Ma’aminim known to us today reveal some aspects of their multilayered messianic religion, including the manner in which they integrated Jewish and non-Jewish mystical beliefs and practices. These sources were composed in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a period during which tremendous cultural and political reforms took place in Ottoman society. The writings of the Ma’aminim were first exposed in the twentieth century by community members who had abandoned their faith and Sabbatian heritage in favor of assimilating into the so-called secular society of the Turkish Republic. Research into these writings was initially carried out within Jewish studies, particularly by scholars whose interest and expertise lay in understanding Sabbatian texts in the context of other Jewish sources. These researchers viewed the Ma’aminim as a transgressive, outcast sect that nevertheless was still part of Jewish culture, giving little attention to their interaction with the non-Jewish environment.

In the last two decades, Jewish studies scholarship has begun to widen the perspective on the inner-communal sources of the Ma’aminim to include general references to non-Jewish traditions. Recent research also sheds light on the social history of the Ma’aminim by focusing on external Ottoman sources, incorporated with contemporary evidence from the community's descendants, who attempt to reconstruct the tradition of their ancestors.

Among the sources now available to researchers are communal songs. The corpus of Ma’aminim songs comprises five manuscripts that differ one from the other in scope, length, and content. Only one of them was fully published, about seventy years ago, in an annotated scholarly edition, titled Sefer shirot ve-tishbaḥot shel ha-Shabta’im (A book of songs and praises of the Sabbatians). The editors—Moshe Attias, Izhak Ben-Zvi, and Gershom Scholem—were the first to deal with this corpus. Their introductions and footnotes focus mainly on aspects and themes that emphasize the Jewish character of the Ma’aminim and, accordingly, identify a range of concepts adopted from the Jewish and kabbalistic-Sabbatian traditions. They also highlight characteristics of the Judeo-Spanish tradition, traced primarily through the use of Ladino (Judeo-Spanish) as their primary language. Because of these interests, only part of the texts that were written in Turkish (in Hebrew script) were copied and translated. The editors' internal Jewish focus, treating non-Jewish Ottoman culture as a negligible influence, was typical of their era.

In a 2001 article, Paul Fenton showcased initial steps toward a cross-cultural approach to the sources, pointing to elements that link the Ma’aminim’s songs to non-Jewish Ottoman culture. One of the elements that Fenton addresses is the incipits that appear in the headings of some of the Sabbatian songs in the manuscripts; these incipits indicate the Ottoman Turkish song (identified by its first words) according to whose melody the Sabbatian song is to be sung. Judging from a few of the incipits, which contain expressions of love, Fenton supposes a Sufi influence on the songs of the Ma’aminim and claims to have identified the original Ottoman song referenced in one of the incipits. Later scholars have followed in Fenton's footsteps and indicated non-Jewish cultural aspects of a few texts in the corpus.

As part of an extensive research project that focused on the cross-cultural contexts of the songs of the Ma’aminim, I was able to locate many of the Ottoman songs indicated by the incipits. In what follows I present my findings, demonstrating the significant contribution of the incipits to understanding the songs of the Ma’aminim in a wider cultural historical context, thereby filling a lacuna in the study of the internal writings of this group.

* * *

Read the rest of Feldman Samet’s article Ottoman Songs in Sabbatian Manuscripts: A Cross-Cultural Perspective on the Inner Writings of the “Ma’aminim” in JQR 109.4 (Fall 2019).