Our Children, Ourselves

A Moroccan Jewish newspaper's appeal to young readers a century ago has echoes in today's media.

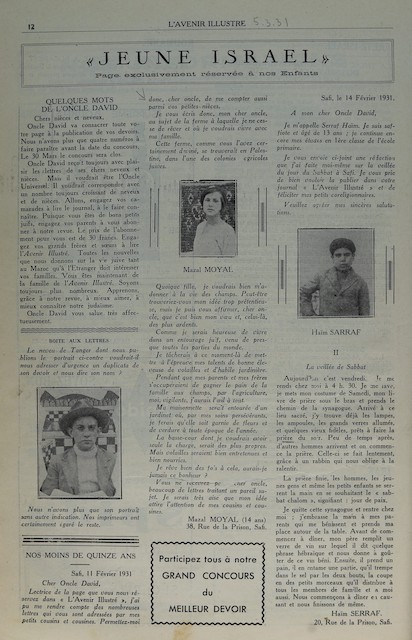

In JQR 112.2, David Guedj writes about a set of essays written by Moroccan Jewish children over the course of a few months in 1930–1931. The essays were published in the Casablanca Jewish newspaper L’Avenir illustré, as the paper tried an experiment: emulating a new interest in youth culture pursued by non-Jewish publications, the paper established a page dedicated to the voices and interests of young people. Guedj analyzes the attitudes and concerns on display in the children’s compositions. Out of the mouths of babes come reflections on education, modernity, and Jewish identity that accord with wider concerns of the era among Westernized Jews in Muslim contexts.

On December 4, 1930, the editors announced: “Here is a page especially for you: you, young Israel [Jeune Israël]!” Each subsequent issue contained a page “reserved exclusively for our children,” apparently in the dual senses of authorship and readership, as the majority of the writing featured there was submitted by youths themselves. There was clear editorial intervention, as Guedj notes that the essays mostly touch on “school, the community and its institutions, the family, and the Jewish calendar.” Themes hewed close to the projects of Jewish education and Westernization that characterized the cultural alignment of the paper and its readers but focused on spheres that the adults saw as particular to children.

Today, such an editorial stance, where adults curate content ostensibly true to children’s sensibilities as opposed to their own, is ubiquitous. A prominent example is the children’s section of the New York Times, which includes an editors’ note at the top: “This section should not be read by grown-ups.” The section premiered during the phase of the pandemic when parents were at wits’ end with children kept home from school, and appears only in print, presumably to lure kids away from their internet-enabled devices. It features craft projects, descriptions of unusual jobs, debates over the best video games, and interviews and short submissions by kids. Typical headlines read “Soap: A Superhero!” and “Dogs Rule! Cats Drool.”

The 1931 essays are a far cry from the irreverent tone of the Times, even farther from the messy science projects and goofy illustrations we see in today’s children’s section. Still, the children in both papers, nearly a century apart, seem to parrot ideas and attitudes from the adult world. In the Times we read children’s reactions to current events like the threat of Covid-19, the war in Ukraine, and climate change, with kids submitting opinions on when schools should be reopened and calling for more care for the environment. In L’Avenir, the young Georges Sebbag from Oran wrote in to say that modern yeshivas “engrave Judaism in the hearts of young Jews and show them its beauty”; and Fabien Cohen complained that “some Jews today … are prone to conceal their Jewishness in shame.”

The cultural and political issues are different but in both settings the children’s worlds and words are determined by the adult imagination—and may say more about the adults of the era than about the youth. JQR’s contributors have found similar phenomena elsewhere. For example, check out Elisheva Baumgarten’s “A Century of Childhood” (2020), commenting on Solomon Schechter’s “The Child in Jewish Literature” (1889); and read the forum on Jewish Paideia in the Enlightenment (2016), especially Iris Idelson-Shein’s “The Beginning of the End: Jews, Children, and Enlightenment Pedagogy” and Dorothea Salzer’s “Adam, Eve, and Jewish Children: Rewriting the Creation of Eve for the Jewish Young at the Beginning of Jewish Modernization.”

Plus ça change; adults will make children mirrors of themselves. But the progression from eighteenth-century storytelling to the twentieth-century youth essay page to the twenty-first–century embrace of gross-out culture also says something about the evolving colonization of childhood. As Michael Chabon commented in his 2009 Manhood for Amateurs, “childhood culture—that combination of lore and play—is now the trademarked property of adults.” And adults may even be its more avid consumers: the marking of the children’s sections as off-limits to grown-ups is an obvious fiction. Adults scanning these pages are informed not about children’s inner worlds, which are and ever will be mysterious to us, but about how our most dearly held concerns can be rendered childish.