Katz Center Fellow Marc Herman on Medieval Judaism, Islamic Legal Theory, and a New Genre of Jewish Thought

This blog post is part of a series focused on the research of current fellows. In this edition, the Katz Center’s Becky Friedman sits down with Marc Herman, who researches the ways that medieval Jews deployed Islamic legal theory when writing about the Oral Torah.

Becky S. Friedman (BSF): Marc, congratulations on the recent publication of Accounting for the Commandments in Medieval Judaism, which you co-edited with Jeremy P. Brown! Let me begin with a big question. It seems like the idea of following the commandments is something Judaism inherited from the Bible, but this new volume calls attention to the importance of medieval Jewish thought in shaping the significance of the commandments in Jewish life. For readers unfamiliar with this period, can you give us some sense of how medieval Jewish thinkers influenced the understanding of the commandment in Judaism, perhaps an example or two uncovered by the volume?

Marc Herman (MH): We tend to think of the commandments as basic to Israel’s covenant and to how Jews imagined Judaism. But the commandments as a category is tremendously broad. Professor Brown and I argue that looking at how Jews tackled this underdetermined category can bring together subfields within Jewish intellectual history that are usually treated as distinct units. (Hence the rather unwieldy subtitle “Studies in Law, Philosophy, Pietism, and Kabbalah.”) Using all of these modes, Jewish thinkers shaped Judaism around the amorphous idea of commandment. Some of the studies look at particular commandments, like how Jews treated divorce or brought a kabbalistic lens to the incest prohibitions. Other studies explore the commandments as a vehicle for thinking about the law as a whole, as a stand-in for what Jews thought that Judaism represented. We have a fancy phrase for it in our opening essay: we call the commandments a “discursive nexus” of medieval Jewish thought.

BSF: I realize there are too many topics covered in the book to address in a brief interview, but I am curious about the commandments that are probably best known to a general audience, the Ten Commandments. Can you share an insight or two from this volume about the Ten Commandments as understood in medieval Jewish philosophy?

MH: The Ten Commandments are sometimes considered a synecdoche of what God wants, sort of a summary of the entire law. Our volume has two articles that address the Ten Commandments directly. Mariano Gomez Aranda, of the Spanish High Council for Scientific Research, talks about how Abraham Ibn Ezra considered the Ten Commandments using a staggering array of investigative tools, including philosophy, mathematics, and astrology. This article underscores, like the whole volume, that the broad category of commandment highlights the diversity of Jewish thought. And Avishai Bar-Asher, of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, uncovers a surprising feature of thirteenth-century kabbalah. Even though many kabbalists focused intensive speculation on the ten sefirot, they didn’t produce a one-to-one correspondence between the sefirot and the Ten Commandments. If you want to know why, you’ll have to read Bar-Asher’s article!

BSF: And turning to your own research, can you tell us a bit about your project here at the Katz Center this year?

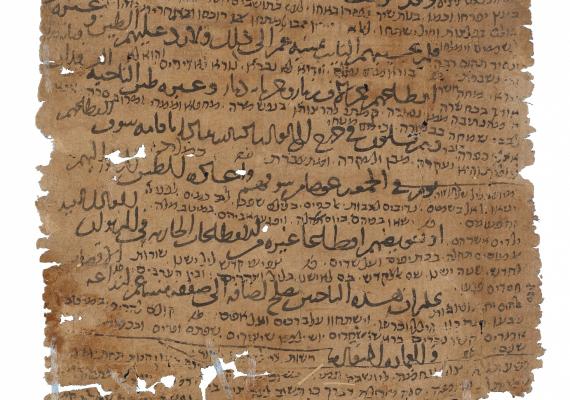

MH: I’m currently finishing up a draft of my first book, which examines how medieval Jews who lived in the Islamic world thought about revelation and the ancient rabbis. My basic argument is that Jews utilized untold categories from nearby Islamic considerations of tradition to help them shape Judaism. For example, Jews fiercely debated the role played by the rabbis of late antiquity: Did they create new laws, or did they just transmit received traditions that date to Sinai? I demonstrate that whatever ways they answered this question, Jews used categories from similarly situated Muslim authors. In short, the mental maps of religious law were broadly shared between Jews and Muslims.

BSF: This year’s fellowship theme is “Rethinking Premodern Jewish Legal Cultures.” In the Jewish legal culture you are focused on, Islam has a huge impact. Can you briefly explain how Islamic legal culture has influenced Jewish legal culture?

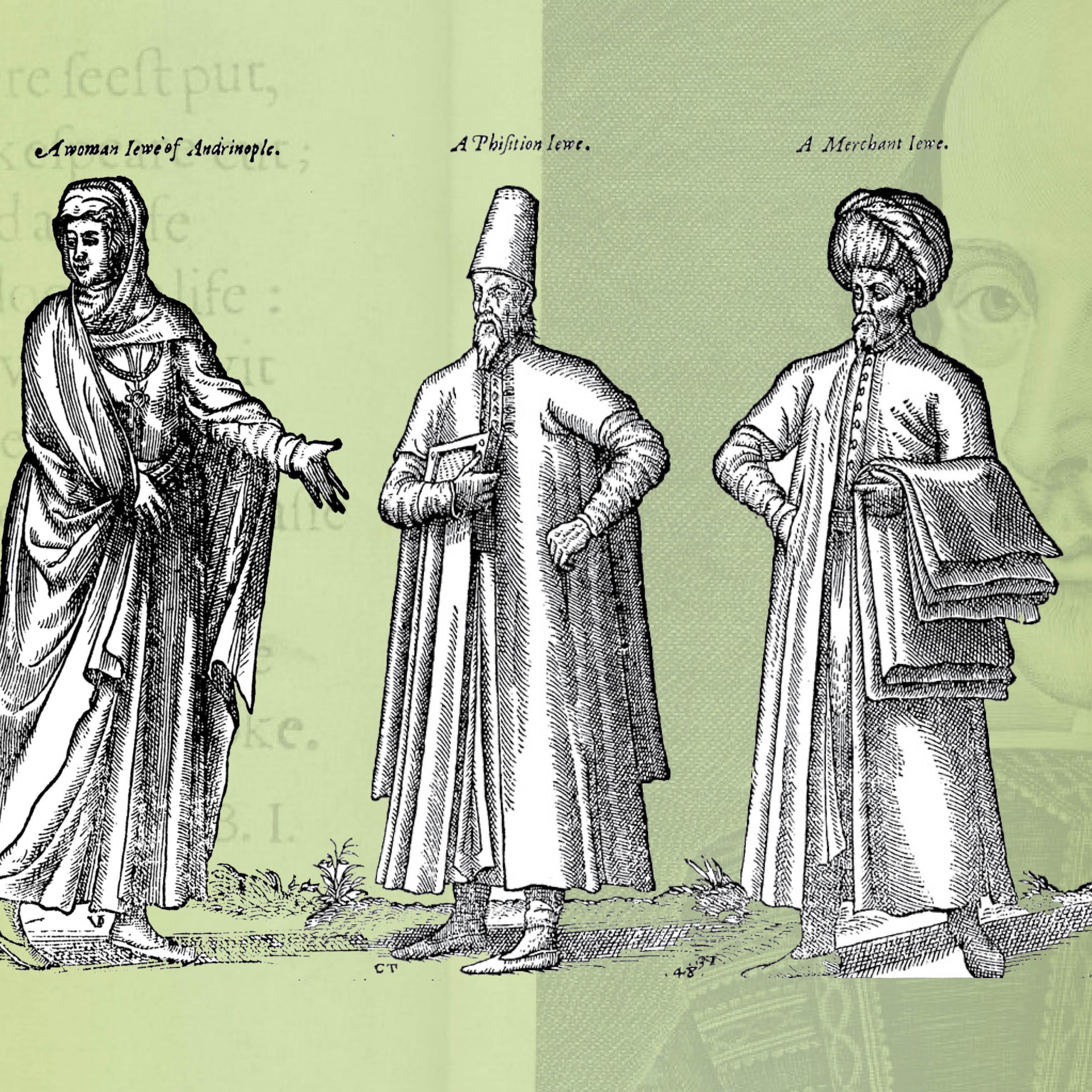

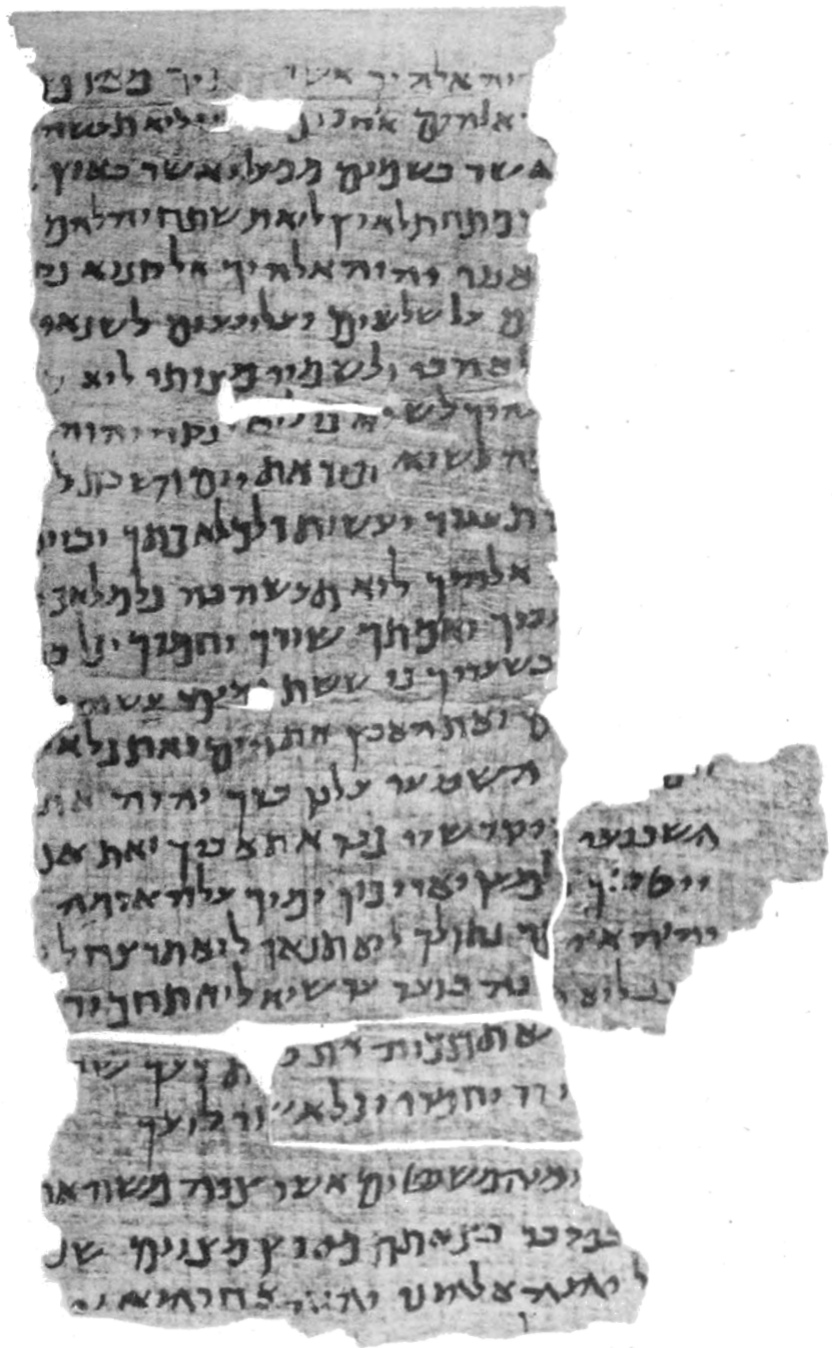

MH: That’s a great question! Jews had a legal culture long before they came under the aegis of Islam, even before they were known as Jews. But the spread of Islam brought about many changes to Jewish societies. In addition to bringing together something like ninety percent of world Jewry into a single cultural sphere, Jews now found themselves in a world where the dominant religion—politically, if not numerically—was similar in structure to their own. Like the adherents of Rabbinic Judaism, Muslim elites prized the “legal sciences.” My research focuses on a particular subset of these legal sciences, formal legal theory. There was no literature of legal theory among Jews before the advent of Islam, but suddenly Jews in the tenth century begin to think about big methodological questions of law: How does interpretation work? What is the basis for legal authority? I suggest that Islamic legal theory stimulated this new genre of Jewish thought.

BSF: How did you find your way to your intellectual interests? For someone brand new to the study of medieval Jewish religious thought, can you recommend a reading in English to get us started?

MH: Medieval Jews, I’ve always thought, inherited such a diverse tradition. Biblical religion and ancient Judaism gave them so many competing ideas about what we would consider foundational questions about Judaism. How does God relate to Israel? What is the purpose of religious law? What is the relationship between rabbinic traditions and biblical texts? The medieval period, for the first time in Jewish history, allows us to peer into the world-making of individual thinkers. This is the first period of Jewish history that offers us enough reliable evidence of the Jews (always elites) who needed to sort out and craft Judaism. And they did so in myriad different venues, producing philosophy, scriptural commentary, and law in totally new ways. I find watching these thinkers in action terribly exciting—they face challenges head-on and endlessly give new shape to their tradition.

The bookshelf of scholarly studies of medieval Jewish thought has exploded in recent decades. Of course, nothing beats study of the primary sources. The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization is collecting and translating a vast range of these texts. Their medieval volumes should be out in a couple of years. (Full disclosure, I've been involved in the productions of these two volumes.) In terms of scholarly work, I often recommend Sarah Stroumsa’s Maimonides in His World as a book that displays new scholarly considerations of even well-known figures. Stroumsa takes the best-known medieval Jew, Moses Maimonides, and shows us that we can see him afresh when we consider the world around him and give full attention to his entire corpus. If that can be done for Maimonides, it can certainly be done for those who have attracted less attention.

BSF: Beyond congratulating you on the new publication, I also want to congratulate you on beginning a new academic position! Can you tell us what is next for you professionally?

MH: Sure! Next year I will begin a position at York University in Toronto. I’ll be based in the Koschitzky Centre for Jewish Studies and the Department of Humanities. York has a long tradition of teaching medieval Jewish intellectual history, and I am excited to be part of its strong Jewish Studies faculty. Being housed in a diverse and broadly conceived department (who else has a Department of Humanities?!) will allow me to interface with a range of scholars and disciplines. I’m really excited!