What Do You Know? Jewish Migration to Latin America

In the series What Do You Know?, we feature scholars’ answers to questions about Jewish history and culture submitted by our readers.

Q: An anonymous reader asks: Why are there so many Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews in Latin America?

A: Current fellow Aviad Moreno answers:

A common assumption is that Jewish migration from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) is a unique episode resulting from national tensions across the Middle East and North Africa after the establishment of Israel in 1948. However, Jewish migration from that region to Latin America did not begin in the mid-twentieth century, but rather evolved within a completely different context. It is a little-known story situated at the crossroads of Middle Eastern and global history, Jewish and non-Jewish migrations, with origins far beyond the Arab-Israeli conflict.

The first Jewish settlements in Latin America actually took place while royal decrees still banned Jews in Spanish and Portuguese colonies throughout the continent. “Crypto-Jews” or “New Christians,” converts to Christianity during periods of persecution of Jews and Muslims, arrived with colonial expeditions after 1492, mostly to Dutch and British territories in the Caribbean, at a time when most Iberian Jews resettled in the Ottoman Empire and Morocco.

Centuries later, many more Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews migrated to Latin America under different circumstances. From the last third of the nineteenth century to the outbreak of the first World War in 1914, the world witnessed a new kind of migration on an unprecedented scale, as the European colonial system replaced slaves with indentured laborers. Tens of millions of people moved within Europe, and from Europe to Africa, Asia, and then to the Americas and Oceania, as the world saw momentous industrialization and economic boom times. This era came to be known as the “age of mass migration.”

Migrations from MENA at this time are often overshadowed by the mass European (Jewish and non-Jewish) immigration to the Americas. Less known is that in the Middle East, the global movement manifested itself in the movement of about 2.5 million Muslims from Russia to the Ottoman Empire, and in the movement of hundreds of thousands of people from southern Europe to North Africa, including Egypt. The inhabitants of the Middle East, the Balkans, and North Africa were also more mobile than ever before, within and beyond the region itself.

Brazil and Argentina, major hubs for MENA immigrants, were two global immigration destinations in Latin America that had lately gained independence from Portugal or Spain. National aspirations for economic expansion, coupled with the need for a steady labor supply, led these countries and others to adopt liberal immigration policies, expressed in the slogan “to govern is to populate.” Some of them set up immigration agencies in Europe, for the express purpose of achieving those aims.

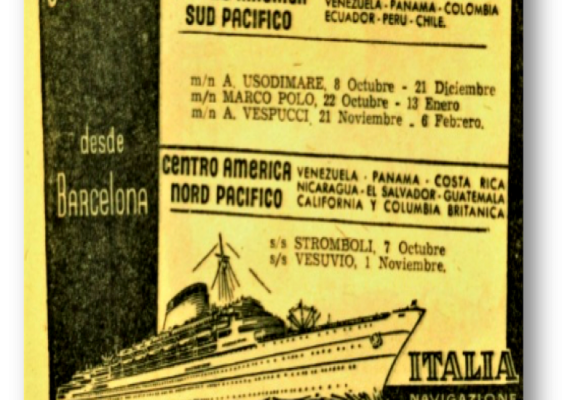

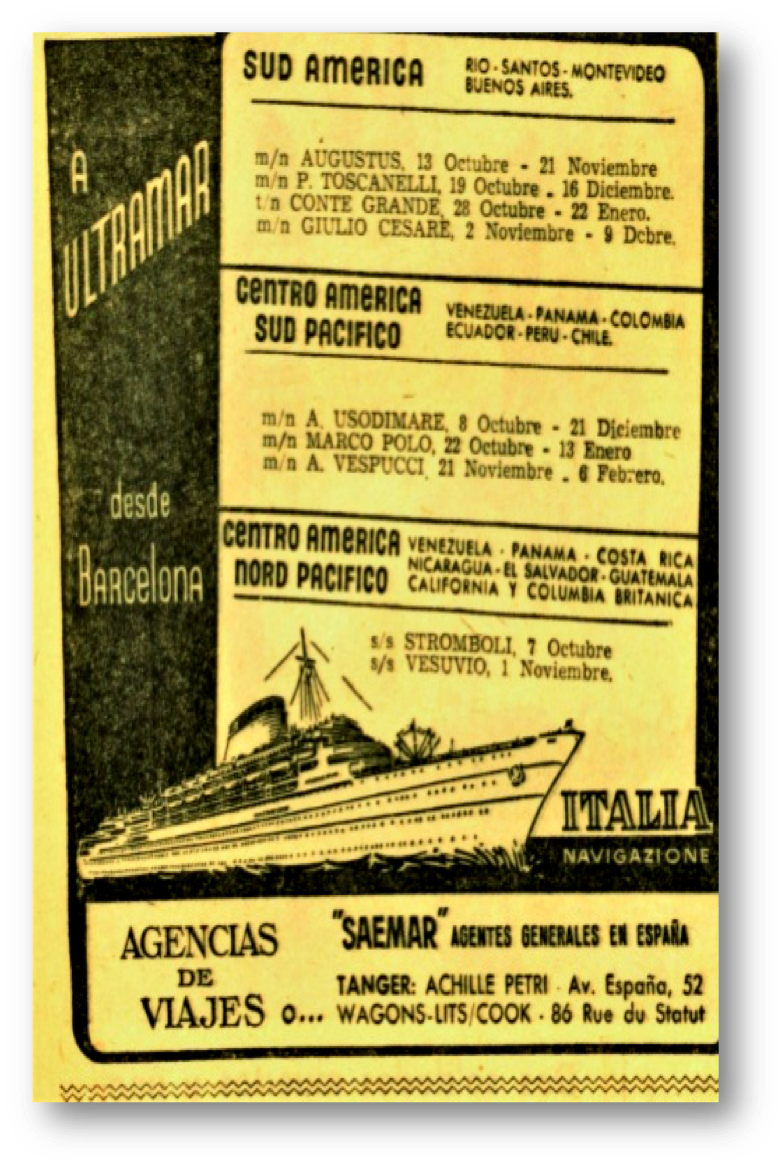

For example, Moroccan emigration to Latin America began as early as 1810, when a few Spanish-speaking Moroccan Jews (descendents of expelled Jews from Spain in the fifteenth century) began to work as regatões, Amazonian river peddlers, traveling between towns and cities across the Brazilian Amazon. The end of the nineteenth century marked the “rubber boom” in that area, and the Brazilian government published pro-immigration propaganda offering foreigners a government labor contract and benefits. The Amazon River and its tributaries were opened to foreign shipping that would link the Brazilian cities of Belém and Manaus with Lisbon, and Barcelona with the Azores, Marseille, Genoa, and Tangier.

The change in migration policies in independent Latin American countries also marked a shift in their attitude towards religious minorities within them. In Brazil, the Imperial Constitution of 1824 recognized Roman Catholicism as the official religion, but the right to practice other religious rites in private was also signed into law. A later constitution in 1889, during the First Republic of Brazil, guaranteed full religious freedom for all. In the 1880s, the Argentinian congress passed a series of laws that stripped the Catholic Church of many of its prerogatives, paving the way for an officially tolerant religious attitude. In the 1920s, when the United States government began to close its doors due to economic crisis, world Jewish organizations began to see Latin America as an alternative heaven for Eastern European Jews, mostly in new agricultural settlements.

In Syria and Lebanon, wellsprings of emigration from the Ottoman Empire during those years, we witness a tendency of various non-Muslim minorities—Maronites, Catholics, Greek Orthodox, Druze, and Jews—to emigrate to the Americas. Many scholars see the 1909 decree, after the Young Turks revolution of 1908, that demanded military service of non-Muslims as the event that sparked migration. Many of these immigrants spoke Arabic regardless of their religious background, while a minority of Jews spoke Ladino.

In Morocco, emigration to Latin America was largely a Jewish phenomenon, though no less connected to global and local developments. While many came as graduates of the French Alliance Israélite Universelle schools that began to set up camp across the MENA region from the mid-nineteenth century (the first branches were opened in northern Morocco in the 1860s), it was their geographic proximity and cultural connection to the Spanish world that connected them to Latin America more effectively. Growing Spanish immigration to northern Morocco overshadowed Haketia, the ancient local Judeo-Spanish dialect, resulting in a momentous and smooth transformation to modern Spanish among Jews. The average Latin American tended to associate Jews from Morocco not with one of the two groups of Jewish immigrants in the country—the “Turcos” (Turks, meaning Arabic-speaking Jews) or the “Rusos” (Russians, meaning Jews from Eastern Europe)—but rather with the non-Jewish Spaniards who flooded the continent in large numbers. After 1948, Latin America continued to attract Jews from across the Middle East, especially Turkish, Lebanese, Syrian, and Moroccan Jews who joined established communities in the continent alongside other destinations throughout the world.