Katz Center Fellow Agata Paluch on the Literature of Early Modern Practical Kabbalah of East-Central Europe

This blog post is part of a series focused on the research of current Katz Center fellows. In this edition, Center director Steven Weitzman sits down with Agata Paluch to explore her research project, "Between Kabbalah, Magic, and Natural Science in Early Modern East-Central Europe."

Steven P. Weitzman (SPW): Can you tell us a little about the research you've been pursuing here at the Katz Center?

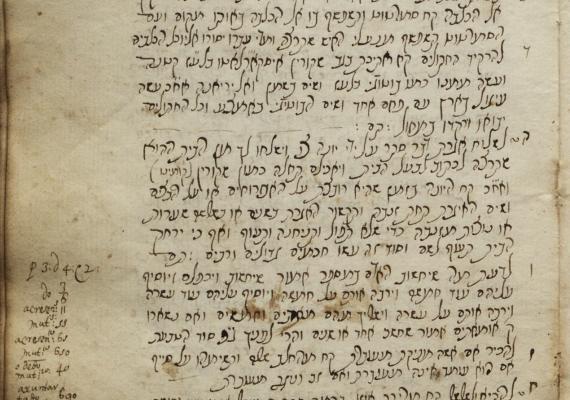

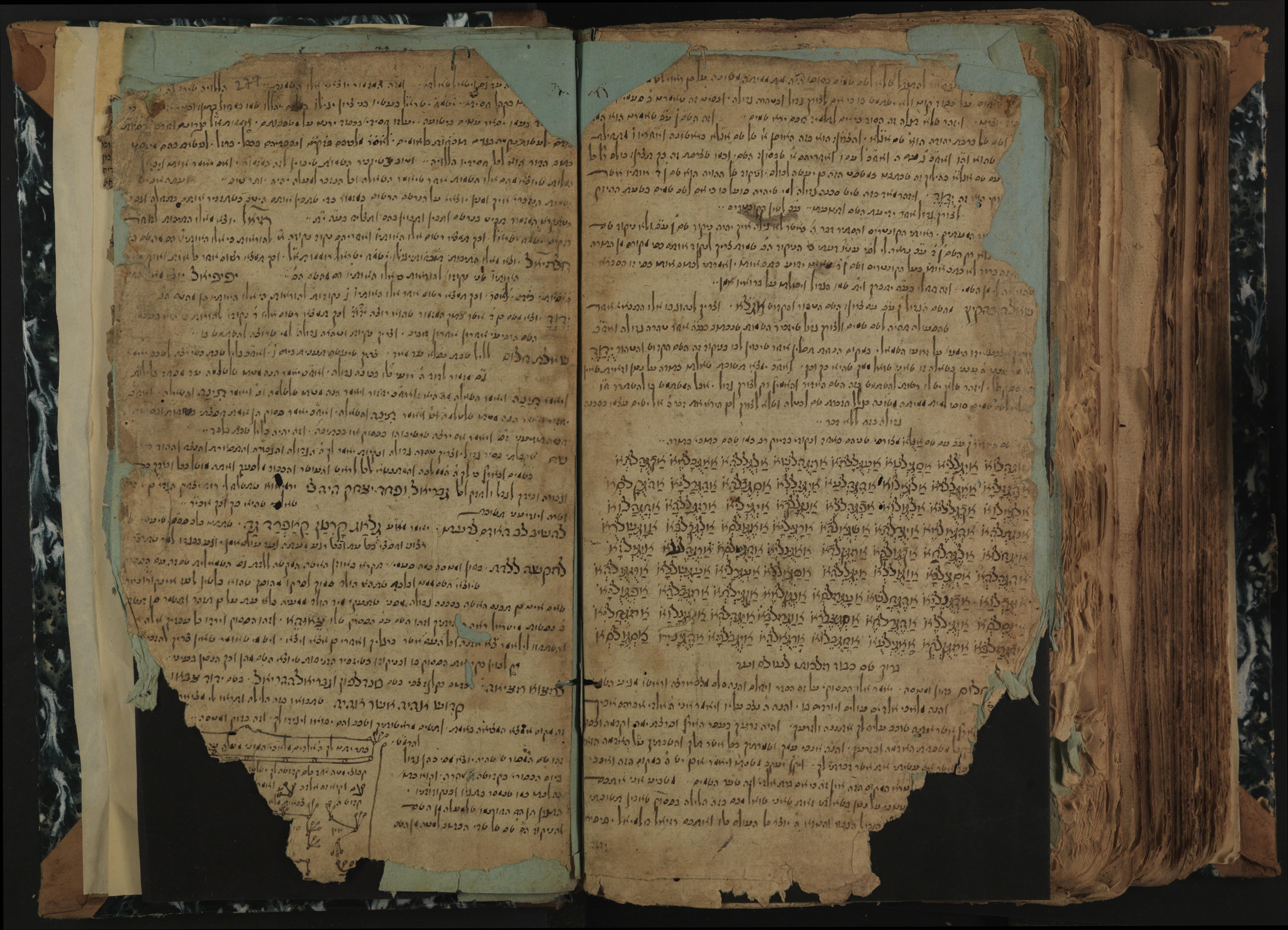

Agata Paluch (AP): I’ve been focusing on the literature of early modern practical kabbalah of the East-Central European provenance. My research examines the extent to which the kabbalistic engagement with both the natural and the supernatural world facilitated and, at the same time, was expedited by the concomitant spread of the nascent experimental sciences in East-Central Europe in the seventeenth century up to the early eighteenth century. I’m particularly interested in the re-evaluation of the role and forms of thriving early modern manuscript culture in the transmission of practical and kabbalistic knowledge.

SPW: This and other research you've done focuses on understudied esoteric traditions in early modern East-Central European tradition. What led you to take an interest in this kind of subject?

AP: Scholars of early modern Ashkenaz have suggested that by the sixteenth century, the speculative theosophical kabbalah became part and parcel of the educational curriculum of the Jewish intellectual elite. Also, especially in the seventeenth century, the so-called "practical kabbalah" associated with magic and a talismanic approach to religious ritual has been claimed to have gained substantial popularity. At the same time, with regard to Central and Eastern Europe the spectrum of early modern Jewish mystical and kabbalistic beliefs and practices remains largely unstudied, with its literary output often unfairly described as unoriginal and peripheral to the study of Jewish mysticism. I found this discrepancy in scholarly assessments puzzling and inviting further research, which has revealed a particularly rich and multifaceted intellectual tradition. My broader project, of which the research pursued at the Katz Center is a part, explores a large corpus of (broadly defined) kabbalistic manuscripts and printed materials of Ashkenazi provenance, placing it within the wider context of early modern intellectual history.

SPW: How are Jewish mystical and magical practice in the early modern context you focus on different from mysticism and magic in earlier periods?

AP: Kabbalah in the regions termed Ashkenaz had emerged in the late-Middle Ages out of various ancient and earlier-medieval mystical, philosophical, and magical traditions. While it evidently assimilated the theosophical kabbalah of the Zohar—the "canonical" kabbalistic corpus written in Spain during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries—the Ashkenazi kabbalah was still anchored in a set of older esoteric traditions of its own, e.g., on the origins of evil, on demonology, angelology, or the tension between divine transcendence and immanence. It also remained faithful to many of the exegetical methodologies of its Ashkenazi predecessors, such as the twelfth–thirteenth-century Rhineland pietists known as Haside Ashkenaz, and other mystical groups active in medieval Ashkenaz. This connection to the specifically Ashkenazi medieval esoteric tradition was maintained right through to the early modern era, even though the classical, mostly Spanish, kabbalistic texts had by that time become standard throughout the Ashkenazi world, including Poland.

What obviously changed in the early modern times was that by the late-sixteenth century kabbalah, especially in its magical/practical reinterpretation, was hardly an esoteric matter. While the speculative kabbalah of the elites might have exerted only limited influence on the Jewish masses in East-Central Europe, popular magical traditions and practices did infiltrate the elitist kabbalah to a large extent.

SPW: The traditions you investigate were eventually overshadowed by Lurianic Kabbalah, which completely reshaped Jewish mystical tradition in ways that continue to reverberate until today. How is the kind of Jewish mysticism you study different from that of Lurianic Kabbalah?

AP: In fact, the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Polish kabbalah is so permeated by references to the earlier Ashkenazi sources that it cannot be understood against the background of either the medieval literatures of the Zohar or the Safedian sixteenth-century Lurianic tradition alone. Although it was inspired by the theosophical universe of the Spanish, Safedian and Italian kabbalists, it also preserved and explored motifs that stemmed from the pietistic and magical traditions of medieval Ashkenaz, which did not seem to the Ashkenazi kabbalists to be inconsistent with the classical lore of the Spanish kabbalah nor with Lurianic theosophy.

I’d suggest that what Gershom Scholem, and others after him, had viewed as the universal spread of the speculative doctrines of Lurianic kabbalah in the early modern era may well have been facilitated by the wide dissemination of much more concrete magical and mystical practices, drawn out of an old stock of religious performance techniques, such as the invocation of angelic names, manipulation of the divine name, talismanic divinatory practices and the like. This magical strand of the early modern kabbalah, with its special interest in the mystical and also practical dimension of language, was a latter-day development out of much earlier traditions originating in medieval Ashkenaz.

SPW: Can you share a new insight or two that you've gleaned from your research at the Katz Center?

AP: I’ve focused this year on studying the flurry of handwritten practical kabbalistic "how-to" books in early modern Ashkenaz. The genre was represented by private or family notebooks recording an individual or domestic sphere of expertise, experiment, and testing, as well as by the kabbalistic manuals often produced by the members of the educated rabbinic elite. These books of recipes not only copy and excerpt existing sources or record "folk" customs, but each of them accounts for a particular reader’s and practitioner’s appropriation of knowledge, be it natural and/or kabbalistic, through the process of selection and modification of traditions, textual sources, and personal experience noted on the page. Even if at first glance a rather straightforward and unpromising, the genre of recipe books seems to be an invaluable source for the study of the circulation of knowledge and natural science between various social, cultural, and linguistic contexts.

SPW: One of your interests is the cognitive science of religion. Can you explain what that is and how it relates to your research? If someone in Jewish studies wanted to learn more about this kind of science, is there a reading you'd recommend?

AP: This stems from my interest in approaches and terminologies involved in the study of mystical experiences, rituals and religion. Cognitive science of religion applies tools of evolutionary psychology, anthropology, and neurosciences to answer questions that have been of relevance to historians of religion, such as why certain religious ideas and practices appear and continue through centuries while other vanish, or why some religious behaviors share common features across cultures. The essential reading in the field is probably Bringing Ritual to Mind: Psychological Foundations of Cultural Forms by E. Thomas Lawson and Robert N. McCauley (2002), but more recently I have been very much inspired by the works of Ann Taves, especially her Religious Experience Reconsidered: A Building-Block Approach to the Study of Religion and Other Special Things (2010).

SPW: The research you've presented here covered an incredible range of magical recipes and spells. Do you have a personal favorite?

AP: The thematic range is indeed enormous, so it would be difficult to have one favorite. Those recipes which make it possible to recover a personal experience of the practitioner-scribe are always especially intriguing, whether this reflects concerns and anxieties about health, fertility, material and spiritual wellbeing, physical beauty, or cleaning stained clothes. I’m also fond of recipes for any type of magical mirrors, as they tend to reveal a lot about the early modern models of perception, the mind, and the concepts of self.