Stews, Soaps, Spells, and Salves

JQR’s latest forum looks at the Jewish recipe

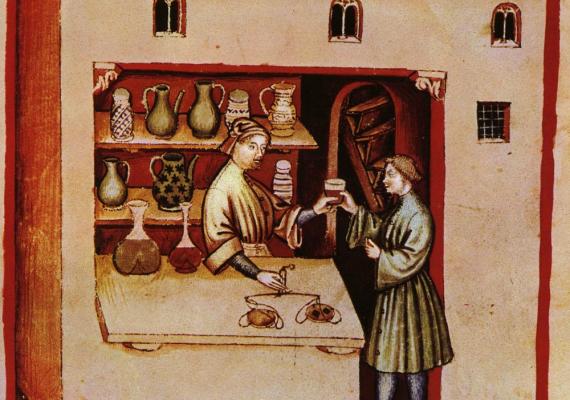

Tacuinum Sanitatis, “Magister Faragius” (Ferraguth) (Naples, 14th c.)

The following is an excerpt from the published introduction.

Have you just been bitten by a rabid dog? Do you have ripe dates in your palm tree and a chicken in your yard but need to impress your dinner guests? Is your hair falling out? Has your skin lost its youthful glow? Are demons threatening your business?

There is a recipe for that.

A recipe is a set of instructions for how to make something or make something happen in the world. Though our own center of gravity for practical instruction lists like this is cooking, for the ancients it was medicine. Physicians wrote, collected, and relied on large bodies of recipes for the preparation of remedies. Beyond that, recipes turn up in a host of other contexts: to guide makers of beauty products, practitioners of alchemy, casters of spells and peddlers of amulets, scribes in want of ink, and, apparently, certain audacious gamblers.

The participants in our forum don’t rely on any particular term for the genre across their varied sources in several languages but instead identify a recipe by its practical admixture of ingredients and prescribed steps that focus on a clearly defined outcome. A recipe is a deictic to nontextual, embodied practice (real or imagined); a how-to, a manual. As a result, literarily, the recipe is marked by a certain humility and lack of self-regard. Its cousin the list, by contrast, asks us to pause on it, pay attention to the meaning of its parts in relation. The recipe is a list with the addition of verbs that generate action, pushing us to move past the page toward the world—both mundane and supramundane. It is a text that directs us, in contra-Derridean fashion, hors de texte. The man with a rash wants a salve to stop the itch. The cake recipe is about the cake.

This is not to say that recipes themselves are not also world-making in the realm of the imagination (a distinctly literary effect). Some early Jewish recipes represented ideals and choreographed the possible, if not the probable. I don’t normally read Yotam Ottolenghi’s recipes while standing in my kitchen wearing an apron but rather extended on my couch, for the vicarious pleasure they promise. So too, Noam Sienna suggests, Saadia Gaon may have collected recipes he would likely never cook himself as a way to signal his intimacy with the habits and tastes of the Abbasid court in Baghdad. Andrea Gondos’s aging beauty in sixteenth-century Italy may have only dreamed of affording the whale ambergris needed for the perfume that would make her smell fresh as a debutante. Sacha Stern’s bumbling medieval Roman calendar makers hoped, perhaps, that their fatal calculations would avert disaster.

In consultation with Agata Paluch and Andrea Gondos who first proposed the idea, JQR invited seven scholars (Marina Rustow, Lennart Lehmhaus, Noam Sienna, Sacha Stern, Agata Paluch, Andrea Gondos, & Anna Shtershis) to bring us a recipe or two and reflect on their form and function. Together, the resulting essays suggest a vast (and understudied) trove of Jewish materials and also show how recipes can do a great deal of work for the scholar: attention to them rewards the historian of science, the occult, and politics no less than the historian of ideas or the everyday.

Find the rest of the introduction and the whole forum at JQR 113.4:

Editor's Introduction: Stews, Soaps, Spells, and Salves

Natalie B. Dohrmann

Medicine, Magic, Alchemy, Food, and Ink: Recipes in the Cairo Geniza

Marina Rustow

Biting, Rubbing, Running, Burning: Recipe(s) for the "Mad Dog" Illness in Talmudic Texts

Lennart Lehmhaus

"He Should Prepare a Sauce": Recovering a Haroset Recipe from 'Abbasid Iraq

Noam Sienna

Difficult Days, Bad Days: Daily Life Recipes

Sacha Stern

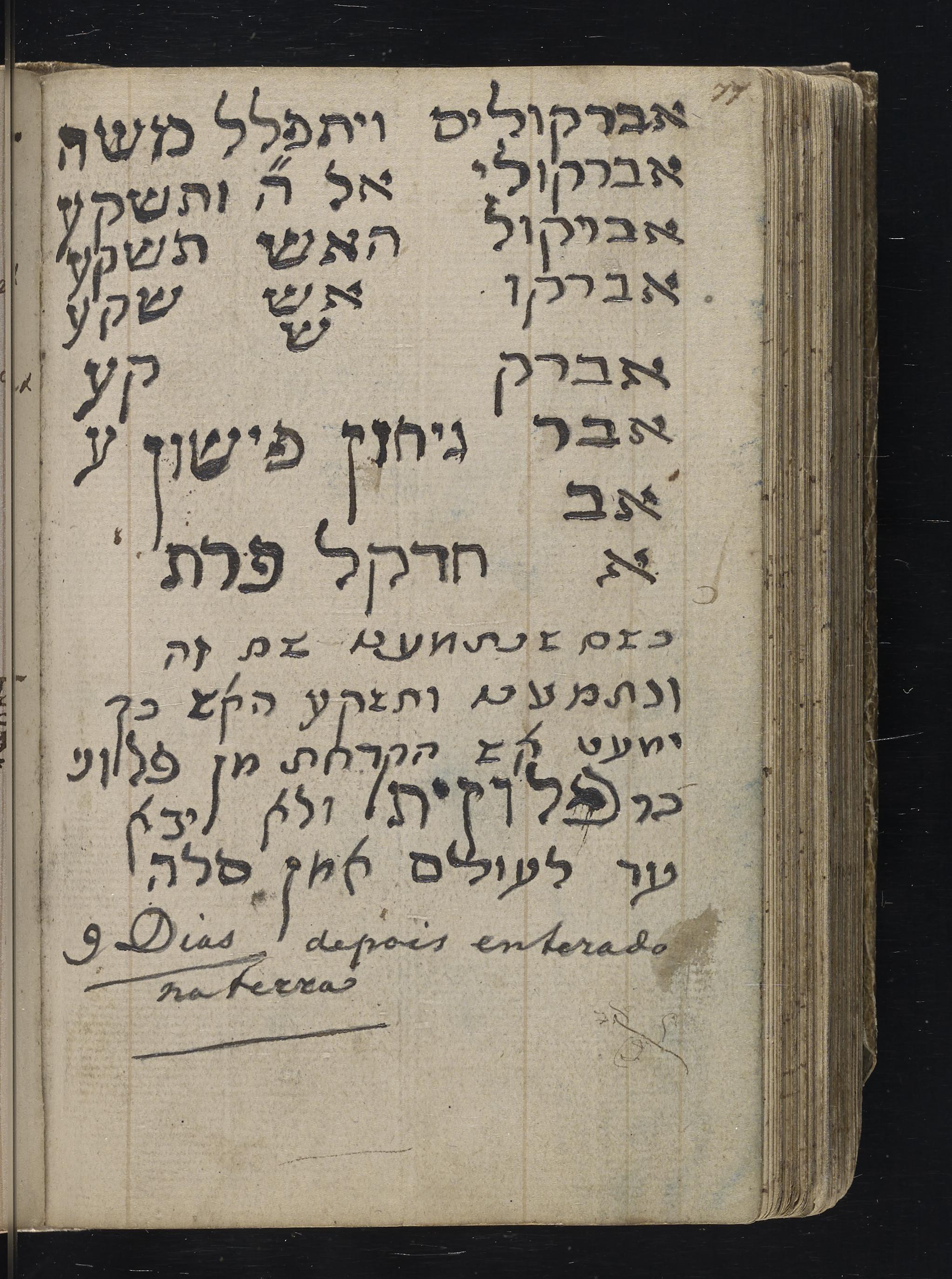

Entertaining Knowledge: Play and Chance in Premodern Kabbalistic Recipe Books

Agata Paluch

Skin Deep: Cosmetics, Body Care, and Practical Kabbalah in Early Modern Jewish Books of Secrets

Andrea Gondos

Sour-Cherry Dumplings and Sweet and Sour Meat: How to Cook for Hostile Friends

Anna Shternshis