New Science in Old Yiddish

An essay in JQR explores early modern Jewish vernacular translations of scientific texts

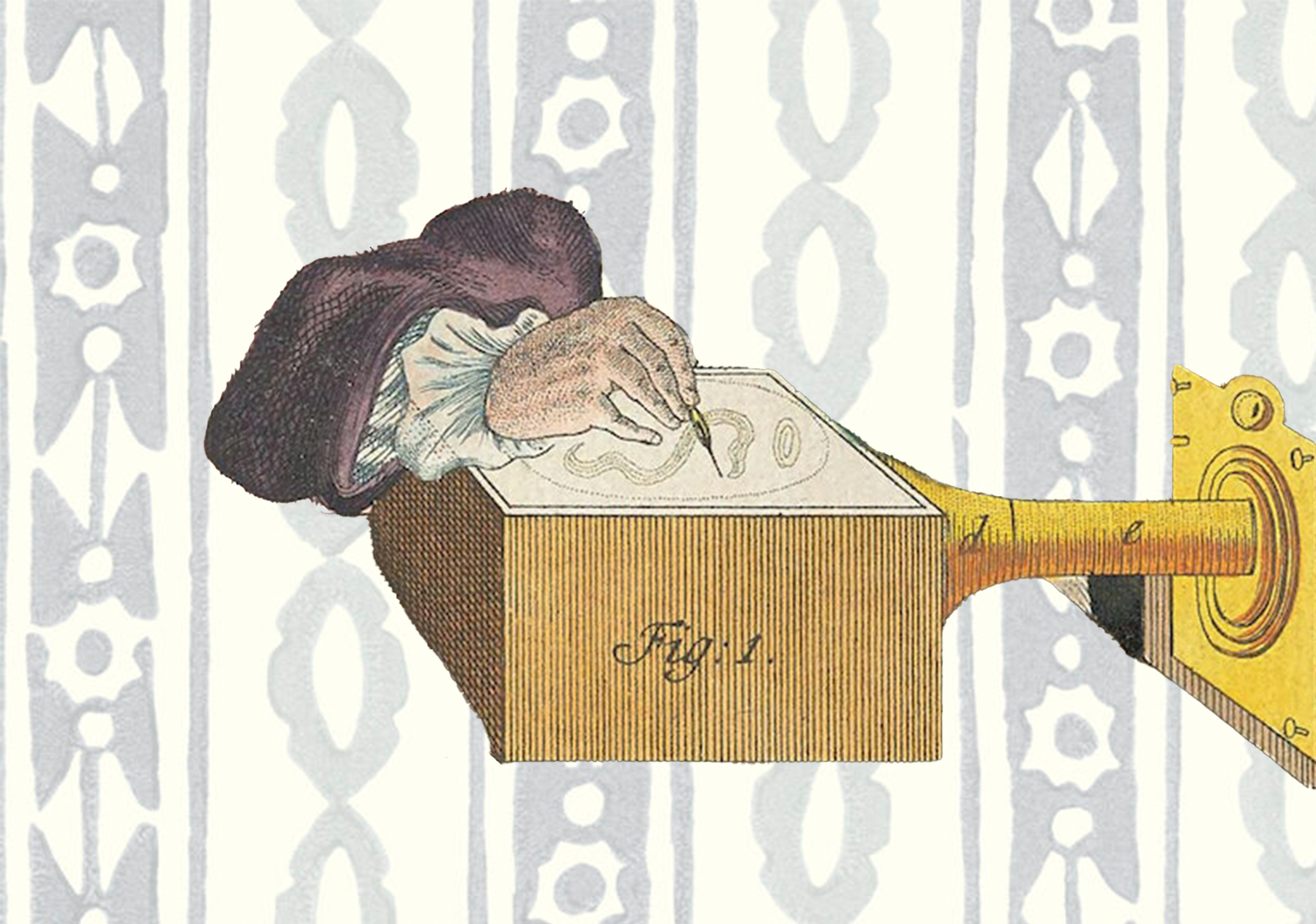

Jan Matejko, Astronomer Copernicus, or Conversations with God, 1873

In an essay in the current issue of JQR, Magdaléna Jánošíková and Iris Idelson-Shein explore new territory in the landscape of early modern Yiddish writing.

Their starting point is a rich body of scholarship on early modern Yiddish translation that opens a window onto the ways Ashkenazi Jewish culture interacted with the cultures of non-Jews among whom they lived. Yiddish speaking Jews translated non-Jewish literary texts into their own language (as treated in another essay by Idelson-Shein), along with genres such as guidebooks, news, and even prayers (as treated by Rebekka Voß also in JQR). In the act of translating, Jewish writers adapted stories, ideas, and sentiments for Jewish readers. These translations were rarely exact renditions but rather versions with creative and practical alterations.

Unlike Hebrew writings, which were only accessible to a smaller, largely male elite within the Jewish population, Yiddish books were accessible across intracommunal boundaries of gender, education, and social status and thus were read more widely. Perhaps because of Yiddish’s association with “low” culture, combined with the misperception of early modern science as being walled off inside an ivory tower, the genre of scientific writing in Yiddish has gone mostly unstudied.

That lacuna is what Jánošíková and Idelson-Shein set out to fill in this essay. Indeed, a robust corpus of scientific works was created in Yiddish over the sixteenth through eighteenth centuries, translated mostly from German and to a lesser extent from Latin and Dutch. The authors give a lively overview of this material, which addresses medical, botanical, geographical, mathematical, and other topics. They show how Yiddish scientific writings were made and consumed by different kinds of people, challenging the notion, as they put it, “that there existed in early modern Europe a tidy division of labor between Hebrew, the language of the learned elite, and Yiddish, the language of the Jewish masses.” Their overview also joins other recent scholarship in revealing, against long-held assumptions, an Ashkenazi intellectual openness to outside knowledge and texts that long predates the Haskalah.

Read the essay here, with open access until October 15, 2023.

And once your appetite for Yiddish studies is whetted, if you or your library has a subscription, you might check out these related essays:

- Rebekka Voß, A Jewish-Pietist Network: Dialogues between Protestant Missionaries and Yiddish Writers in Eighteenth-Century Germany, JQR 112.4 (2022)

- Hannah Pollin-Galay, “A Rubric of Pain Words”: Mapping Atrocity with Holocaust Yiddish Glossaries, JQR 110.1 (2020)

- Iris Idelson-Shein, Meditations on a Monkey-Face: Monsters, Transgressed Boundaries, and Contested Hierarchies in a Yiddish Eulenspiegel, JQR 108.1 (2018)

- Aya Elyada, Early Modern Yiddish and the Jewish Volkskunde, 1880–1938, JQR 107.2 (2017)

- Jerold Frakes, Yiddish Literature's Outliers: Early and Late, Italy and Poland, Rhetorical and Peripheral, JQR 104.2 (2014)

- Ber Boris Kotlerman, “Since I have learned of these evil tidings, I have been heartsick and I am unable to sleep”: The Old Yiddish and Hebrew Letters from 1476 in the Shadow of Blood Libels in Northern Italy and Germany, JQR 102.1 (2012)

- Sarah Abrevaya Stein, Asymmetric Fates: Secular Yiddish and Ladino Culture in Comparison, JQR 96.4 (2006)