The Rule of Sevens in Israel and Zionism

The current issue of JQR includes a set of short essays on particular years of import in the history of Israel and Zionism—all of which, as it happens, end in seven. The essays themselves, linked below, are available with a subscription. Here on the blog, we excerpt JQR coeditor David N. Myers’s introduction to the lot.

Commemorative years are, in a purely logical sense, artifices, no more consequential than the preceding or following year. And yet, they assume lives of their own through the symbolic and affective meanings that we ascribe to them, granting them a presence that is real and full of impact, and projecting an organizing or reorienting focus onto the past. Of course, commemorative years also afford us an opportunity to reflect on the import of past events and the ways in which they continue to inform the present.

The year 2017 is an example of some distinction, particularly for the history of Zionism and Israel. The idea of devoting a forum to 2017 arose, as with so many good ideas at JQR, from our late colleague, Elliott Horowitz z"l, who thought that we should try our hand at offering a fifty-year retrospective on 1967, an undeniably consequential year in the history of Israel and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. As we bounced ideas around, we decided to expand the focus to include other years that end in "7" and see what came of it. And thus we came up with five key years: 1897, 1917, 1947, 1967, and 1977.

JQR asked the five forum participants to gauge the resonances of these key dates up to the present, and the result is an illuminating, if necessarily incomplete, history of the path to Jewish statehood and its multiple effects. Their critical analysis surfaces both achievements and failings of the Zionist project and Israel, as seen from the perspective of 2017.

(Click on each year below to go straight to the essay on Project Muse.)

Derek Penslar opens the forum by juxtaposing the founding meetings of the world Zionist organization and the Jewish socialist Bund, both in the year 1897. He argues that the revolutionary fervor of the Bund did not yield tangible results over time, while Zionism, for all its fractious divisions, did realize its revolutionary dream when a sovereign Jewish state was seated at the United Nations in 1949. Penslar charts some of the evolving and competing sensibilities within Zionism, as well as a number of the unforeseen consequences of the movement that would likely make Theodor Herzl, the founding father of political Zionism, both proud and disappointed if he were to see the state today.

Liora Halperin tackles the impact of the Balfour Declaration, the tersely worded endorsement by the British government on November 2 calling for "a national home for the Jewish people." One hundred years after the Declaration was announced, Halperin identifies a deeply embedded paradox in the document that was present at birth. The support of Western powers, as epitomized by Balfour, has not only been a key source of Zionism's claim to international legitimacy. It has also been a prime cause for the abiding enmity of the Arab world toward Zionism, which it regards as a "highly malevolent colonial force." As Halperin casts it, Balfour was a Faustian bargain which Zionists were in no position to refuse, but which contained the seeds of persistent—perhaps unending—discontent.

Zvi Ben-Dor Benite picks up the story of Zionism's quest for validation with United Nations General Assembly Resolution 181, from November 29, 1947, that called for the partition of Palestine into Jewish and Arab states. He observes the date's hybrid and ambiguous status in Israeli public culture: it is known as "Kaf-tet be-November," a formulation that mixes Hebrew letter-numbers as used in traditional Jewish dating and the gentile month. Ben-Dor Benite then moves on to suggest that the UN Resolution belonged to a unique moment in history, the "long 1947" in which territorial partition was attempted in many different conflict zones around the world including India, Korea, Germany, and Vietnam. The results of this experiment in conflict resolution were decidedly mixed; in some cases, the partition plans were replaced by unification processes of varying degrees of success, and in others, by the continuation of tension-filled divisions of terrain (as in the Koreas). Ben-Dor Benite concludes by noting that Israel's Proclamation of Independence, declared less than six months after Resolution 181, contains some of the earlier decree's language about minority rights, whose fulfillment remains incomplete to this day.

Seth Anziska takes stock of the effects of the 1967 Six-Day War over the course of the past half-century. He recalls at the outset the prediction of the iconoclastic Israeli scientist and philosopher Yeshayahu Leibowitz, shortly after the war's completion, that his country's lightning victory was a major step toward "the liquidation of the state of Israel as the state of the Jewish people." Leibowitz's prognostication was a cry in the wilderness, swept away by the powerful euphoria of both religious and secular Israelis in the war's aftermath. And yet, Anziska argues, there is much in Leibowitz's early admonition that merits our attention today. Israel's occupation of territories conquered in 1967 has the appearance of permanence and serves as an obstacle to the Palestinians' drive for national self-determination. The occupation has been enabled, Anziska observes, by an unbridled celebration of political and military power that is new to Jewish history. At the same time, the 1967 war echoed loudly in the Arab world, inducing an introspective critique of secular nationalism that yielded, among other unintended consequences, a powerful new Islamist voice.

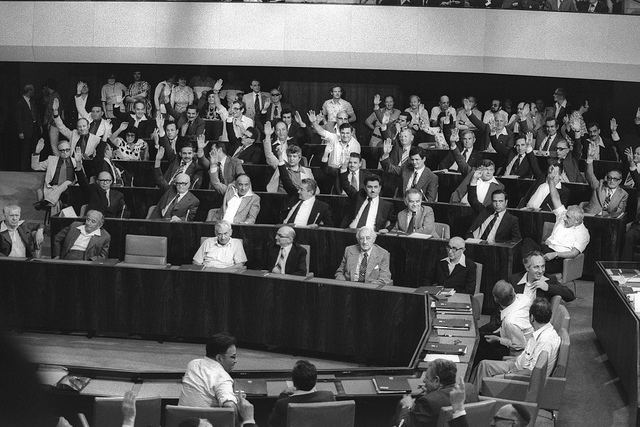

Avi Shilon explains the significance of 1977, the year of the bombshell known as the Mahapakh (upheaval) in Israeli politics. In that year, the long-time Israeli opposition leader Menachem Begin led his Likud party to an electoral triumph, thereby ending thirty years of Labor Party rule. In analyzing this highly consequential development, Shilon isolates two interrelated factors: ethnicity and religiosity. Begin's victory had everything to do with the growing support of Mizrahim, Jews of Middle Eastern origin, who increasingly felt abandoned by Labor and more and more drawn to Likud. According to Shilon, the Mizrahim's middle ground in religious matters—neither fully Orthodox nor secular but rather "traditional"—resonated with Begin's own attitude to Judaism. Their shared reverence for religious tradition was a key factor in the Mahapakh, cementing a deep emotional bond despite the fact that Begin himself was the epitome of a Polish-born Ashenazi Jew. And this shared reverence remains a key element in the fact that parties of the right have led governing coalitions in Israel for thirty-two of the forty years since 1977.

Follow the links above or read the whole issue via Project Muse. A subscription is required; log in through your institution’s library or buy an individual subscription here.

1947

1947 1977

1977