The Red Question Mark

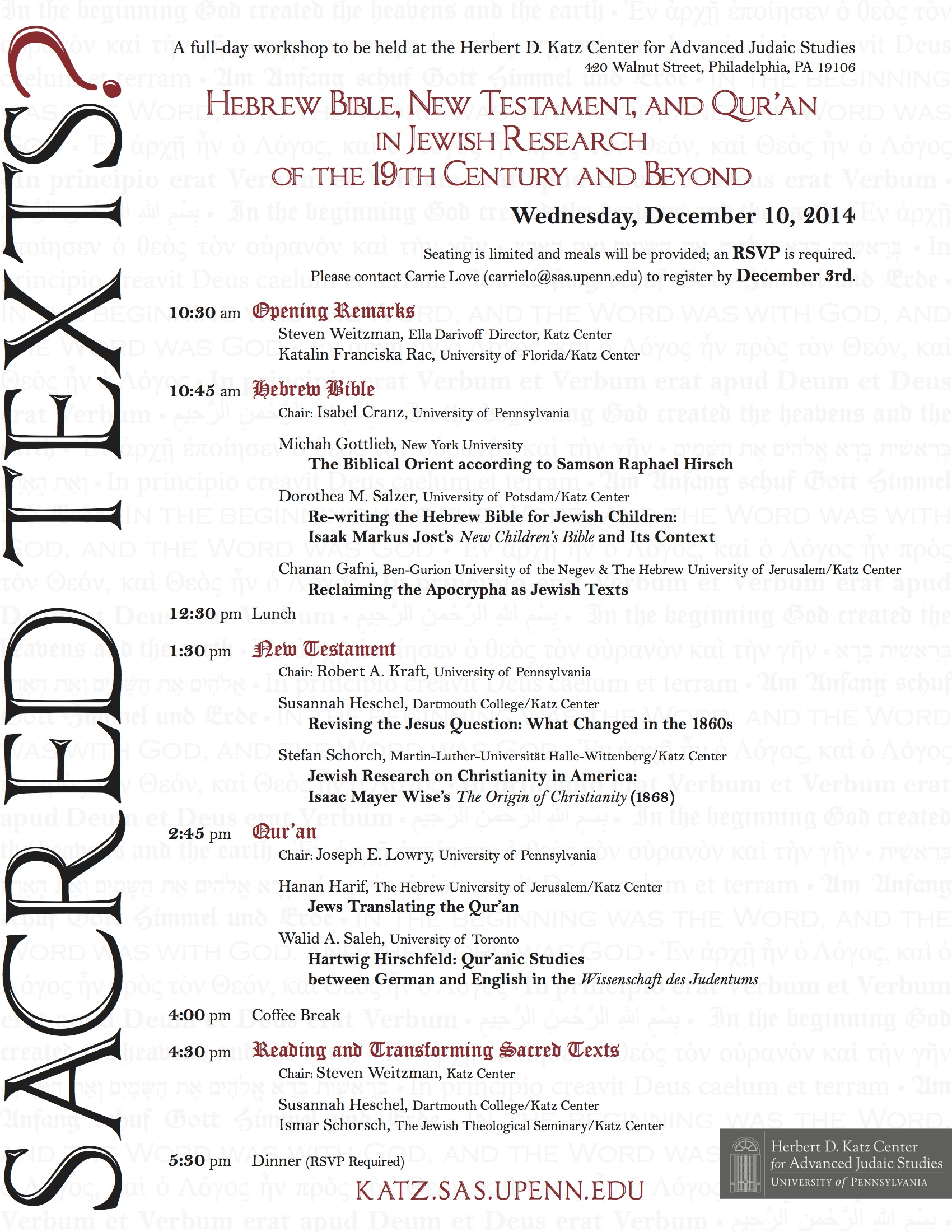

On the official poster for the day-long workshop on nineteenth-century Hebrew Bible, New Testament, and Qur'an studies, the black printing of the workshop’s title is followed by a fat red question mark.

The red ink was well spent, as it turned out: this question mark hovered throughout the day’s lectures and discussions devoted to (in the words of the subtitle:) “Hebrew Bible, New Testament, and Qur’an in Jewish Research in the 19th Century and Beyond.” It was translated into a provocative aporia by Ismar Schorsch, who closed the day by pointing out that the most sacred of all Jewish texts had been missing from the agenda of the workshop—the Talmud! Thus, a day of interesting and often challenging presentations, analyses, and debates ended in the best of all possible ways: with new and more refined questions for all participants.

The study of the corpora of sacred texts became an important and even central preoccupation of many scholars of both the inner circle and the periphery of the Wissenschaft des Judentums, bringing to an end what had often been regarded as an intellectual monopoly of Christian theologians. Since most Jewish scholars at that time did not restrict their work to one of the sacred texts, but rather dealt with all the three, new approaches and methods applied in one field would often be adopted immediately within the other fields, leading to important new insights, as the oeuvre of the Prussian scholar and rabbi Abraham Geiger demonstrates.

Moreover, most of the nineteenth-century Jews engaged in these studies had a strong background in traditional or maskilic Jewish education and were therefore able to apply competencies and knowledge not available to most Christian scholars. For example, drawing on their intimate knowledge of rabbinic literature, Jewish scholars could often provide astoundingly simple explanations to difficult passages and shed new light on the New Testament (Isaac Mayer Wise from Cincinnati) or the Qur’an (Ignaz Goldziher from Budapest)

Finally, the workshop demonstrated quite plainly that the protagonists of the Wissenschaft des Judentums were not secluded in an ivory tower. Rather, they were generally very well connected with their communities, to whom they made the results of their work available in publications, translations, commentaries, and school books. As for many scholars today, this was an important part of their work.