Reconstructing the Tower of Babel

As part of my contribution to the Katz Center’s public programming, I offered a workshop to twelve-year-old Hebrew school students on what we learn from retellings of biblical stories, and then included some of their work in a later presentation to adults at the same synagogue. The experience was moving and enlightening for me.

Two days after my workshop, the fellows at the Katz Center came together for a meeting of our reading group. We were discussing a text by Gershom Scholem called Mitokh hirhurim al hokhmat yisrael—“Wanderings of the Mind about Jewish Studies.” This is a rather radical and polemical essay, written in a wonderfully rich and powerful—even emotional—language with all kinds of allusions to the Bible, rabbinic texts, and mystical concepts. One of Scholem’s arguments is that a historian needs to destroy history in order to reconstruct it anew—meaning for him, of course, to use history in a Zionist context.

In the midst of our discussion, it struck me that this is exactly what the children did in retelling the story of the tower of Babel. They deconstructed the biblical narrative, “destroyed” it, so to speak, and changed it into a meaningful construction for themselves, thereby finding a way to give a personal meaning to this old story and make their own path to tradition. Their retellings, simple though they seemed as first, demanded to be taken seriously.

Each child told the story in a way that was different from the others and from the biblical version. They made cultural adaptations in order to explain biblical lacunae and make sense of various textual details. They tried to explain what it means that the tower reached up into the sky and what happened after the language was scattered; sometimes they redefined the tower itself. According to the biblical text, the tower is simply not finished, but for the children this bare fact was an opportunity for creativity; according to some of them, God destroyed it, while others suggested that it fell on its own, or that it was never destroyed at all. The obscurity of the text prompted the students to ask why reaching for the sky incurred God’s wrath. The children’s inventions were invested with moral, psychological, and historical significance.

They not only enacted Scholem’s process of destruction-for-renewal; they also engaged in cultural translation, adapting the text to their experiences just as did the authors of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century children’s Bibles that I’m examining for my current book project. Like the Hebrew school students, those authors felt it necessary to truncate or reshape the text, and in some cases toss it away altogether and start anew. As some of the children observed, the destruction of the tower was itself a deeply creative act as it restored harmony in some mysterious way, and corresponded to the formation of our own polyglot world.

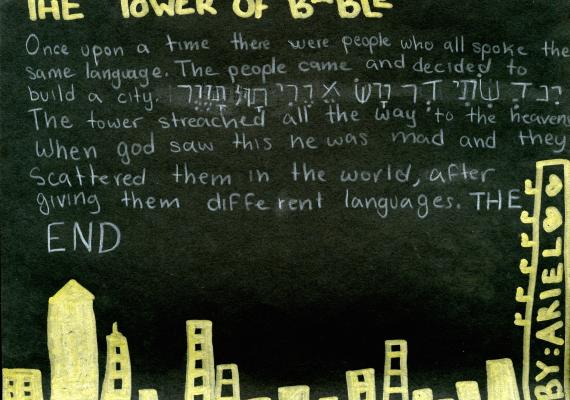

The first story opens with a familiar phrase: “once upon a time.” Does this mean that the biblical stories for this child have the status of fairy tales? More likely, the author means to acknowledge the chronological distance of the story. I also noticed the unusual sentence, “and they scattered them in the world.” When asked about this, the girl who wrote the story said that she wanted to give space for all kinds of perceptions of God. Because there are references to God as man, woman, and other different notions, she wanted to be inclusive and chose the neutral form of “they.” This struck me as very thoughtful and as having a rather meaningful theological component. The student not only wanted to be tolerant and inclusive, she obviously also was very much aware that personal perceptions of God (and different contexts) are meaningful for building a relationship to the texts by which tradition is brought to us, that everybody has the need to find a way to forge a personal connection with the text.

Her illustration shows a skyline that is very similar to the skyline of an American city, with the tower of Babel only slightly bigger than the other buildings, which for me is a clear cultural adaptation. Also, she is one of the few children who actually implemented the city into the picture. I wonder if the choice of color (silver and gold on a black background) is an instrument of orientalization.

Hebrish: “In the city there was a very tall tower.”

This second story was written collaboratively by three girls and is a beautiful rewriting on many different levels. First of all, the story is situated in the future; in addition, the people do not build a tower, but rather a factory for apple phones. Embedded in this structure is a profound critique of our society that prefers texting to actual personal communication. Interestingly enough, the authors also turn the bad ending of the biblical story into a happy one, since the people are not scattered and the tower (i.e., the factory) remains standing—the people “made good use of the amazing factory that they built.” For me, the most striking feature in this text is how the girls tried to figure out a moral of the biblical story for their own time and context, which is exactly what the authors of my biblical stories did more than 200 years ago.

Hebrish: "But soon it change[d]"

For a third student, the story is about God being afraid of the strength of a unified humankind, an interpretation clearly rooted in the biblical text itself (Gen 11:6: and the Lord said, "If, as one people with one language for all, this is how they have begun to act, then nothing that they may propose to do will be out of their reach"). The scattering of the language for him is a means of weakening the collective. Interesting is the feeling of anxiety ascribed to God; God is a very emotional being in the Hebrew Bible—but most of the time the emotion is anger and to the best of my knowledge, never fear. So in showing an anxious God, the author actually questions God’s omnipotence and at the same time shows a human side in God, something to which we can all relate. Although the author does not spell it out, the insinuation of the power of unification is a striking one here, and so the story can be read as a demand to seek more unification in order to achieve important goals.

Hebrish: "Separated them by language."

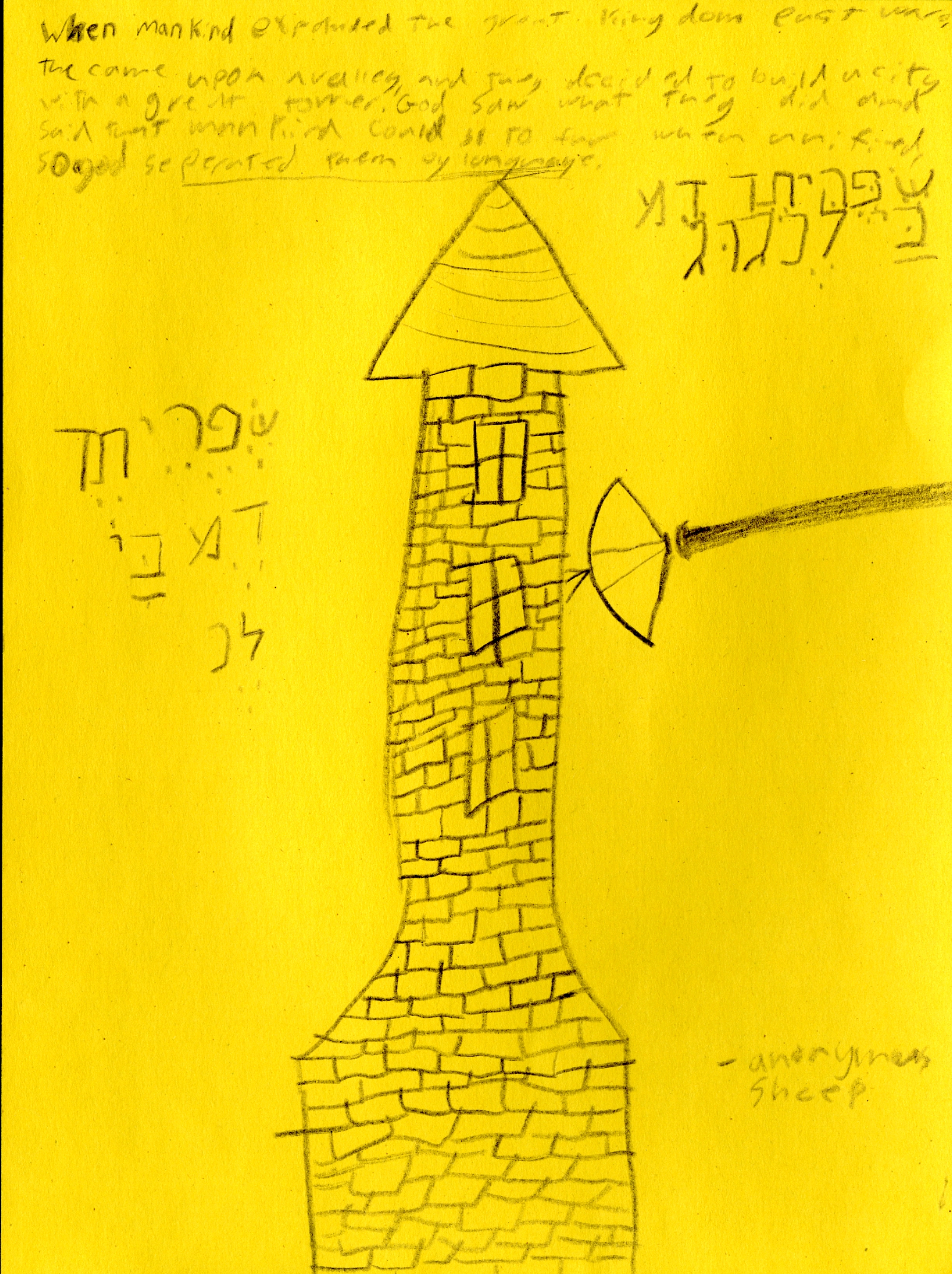

Finally, the student(s) who wrote this text tried to find a reason for building the tower, something the authors of my biblical stories also did. For our author, the people of Babel built a tower so they could explore the heavens. God’s reaction is not rationalized as in the previous text, it is just stated that he saw this was not good. Is this a critique of progress? The author(s) also thought about the question of the consequences of the scattered language and came up with the impossibility of coordination. Again, this can be read as an invitation to think about cooperation. Strikingly, the people themselves destroy the tower, a moment that is also captured in the illustration accompanying the story.

Hebrish: “God made different languages”