Q&A: Katz Center Fellow Ahuvia Goren on the Circulation of the Idea of Circulation

Q&A: Katz Center Fellow Ahuvia Goren traces heated debates over the function of the heart and brain and in so doing reveals the broad and complex circulation of ideas in early modern Europe

Ernest Board, Detail: William Harvey Demonstrating His Theory of Circulation of Blood Before Charles I, Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

Natalie Dohrmann (NBD): Ahuvia, tell us a bit about your broad scholarly interests, and what especially excites you about them personally and/or intellectually.

Ahuvia Goren (AG): My scholarly interests center on the complex relationships between theology, science, and secularism from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. I’m especially interested in how these interactions shaped the conceptual frameworks we still inhabit today. A central question that drives my work is: how have competing narratives about science and religion—both historical and philosophical—shaped modern culture, and how do they continue to inform contemporary value judgments debates and, both within and beyond the Jewish world?

I explore these questions through more focused projects, such as examining the role of skepticism in early modern thought, tracing the reception of ideas like atomism, Cartesian philosophy, and the circulation of blood, and analyzing how such developments impacted Jewish intellectual history. What excites me about this work is that it shows how images and metaphors—more than precise scientific content—have played a powerful role in shaping how people talk about truth, belief, and authority. These representations continue to influence political and cultural conversations about religion today.

Beyond the academic dimension, I find this field meaningful because it often touches on deeper philosophical concerns. In my own journey through various yeshivot, the humanities, and some educational projects, I’ve come to see how profoundly our thinking is shaped—often unconsciously—by inherited horizons, narratives, and categories. In this light, understanding the history of our conceptual vocabulary becomes a way to gain clarity, loosen some constraints, and approach the future with greater critical awareness.

NBD: You wrote your dissertation on doubt and skepticism in early modern Italian Judaism—what is historically specific about these stances, since to an outsider they may seem on first blush to be just natural parts of human thought?

AG: Not only to an “outsider”—honestly, I too tend to take for granted that uncertainty and doubt are fundamental aspects of human thought, just like the impulse toward verification or proof. And yet, as with many things that are seemingly universal, their expression is also shaped by specific historical and cultural conditions. My dissertation tried to trace how certain forms of doubt and skepticism took shape in early modern Italy, particularly among Jewish thinkers, by situating them within the broader epistemic concerns of the time.

Uncertainty, like certainty, is never just a timeless mental state—it is shaped by the norms, vocabularies, and assumptions available in a given era. The opening chapters of my work focus on developments especially specific to Italy, such as the rapid growth of the postal system. This infrastructure allowed for faster circulation of news and ideas, leading to new forms of simultaneity and intensifying questions about the reliability of information. Combined with the rise of new ideas in natural philosophy of the time, the spread of philological and historical methods promoted by humanism and the early Enlightenment, and intense inter- and intra-Christian polemics, these changes gave rise to new modes of argument, doubt, and inquiry.

What I tried to show is how these broader cultural shifts shaped Jewish thinking in particular ways—ways that were both deeply engaged with their Christian surroundings and grounded in internal Jewish traditions. In short, doubt may be universal, but its outlines are historically situated.

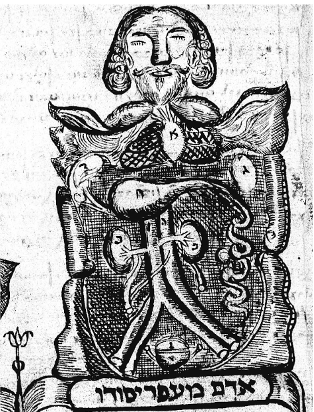

NBD: There is so much to talk about with this image! Can you give us a brief sketch of what is going on here and its significance for you?

NBD: There is so much to talk about with this image! Can you give us a brief sketch of what is going on here and its significance for you?

What we’re looking at here is an image from a Yiddish text written in the early eighteenth century by Rabbi Mordechai of Schmallenberg. His work, Ets ha-Sade, is a remarkable treatise that blends medicine and moral teachings. Rabbi Mordechai came from a distinguished Ashkenazi family and, according to his own testimony, studied French and Latin and also studied medical literature.

What makes this text particularly striking is how it reflects the influence of new anatomical science—such as the ideas of Harvey and Descartes—within early modern Ashkenazi culture. This is not just a medical handbook; it also deals with moral psychology. For instance, the author presents his own version of the six basic emotions described by Descartes, altered only slightly, and likely adapted directly from Les Passions de l’âme.

For me, this image opens up bigger questions: How did early modern Jewish communities encounter and absorb scientific developments—like anatomy—not through formal university training (such as in Padua), but through other, more informal and vernacular channels? And how did those ideas shape ethical and theological thought? Images like this one help us explore the intersection of science and theology during key moments of transformation in both Jewish and Christian cultures.

NBD: Has being part of a residential fellowship made an impact on your scholarship?

AG: My time as a fellow at the Katz Center has been deeply enriching. The most immediate and obvious benefit has been the time, space, and resources to focus on my research. But beyond that, the opportunity to engage closely with scholars who work on similar themes from very different perspectives has been especially stimulating. It has pushed me to think about familiar questions in new ways and to reflect more broadly on the texts and topics I study. Each seminar revealed how a shared theme can unfold into entirely different lines of inquiry, and it was a real privilege to witness and be part of those conversations.

Being part of such a diverse and thoughtful scholarly community was also a valuable reminder of the importance of writing that is accessible and open. In the history of science, it’s easy to become immersed in highly detailed debates or intricate frameworks that speak mainly to a narrow audience. And yet, the questions we explore often touch on issues that are relevant to a much broader scholarly and even public conversation. It's not always easy to bridge that gap, but my time here reminded me that when we write or present our work with that awareness in mind, we can often arrive more quickly at the "so what?" of our research and create the possibility for more expansive dialogue. That’s something I’m actively trying to hold on to now as I write up work that emerged from my time here this semester.