Naftali Levy: An Interesting Species (or min) of Jewish Evolutionist

Big ideas don't come any bigger than Darwinism, and I've spent a fascinating few years looking at the impact of evolutionary theories on Jewish history and culture. I've discovered a wide variety of species of Jewish evolutionists rethinking their texts and traditions: from Italian kabbalist Elijah Benamozegh to religious Zionist Abraham Isaac Kook, from Anglo-Jewish eugenicist Lucien Wolf to US Reform rabbis Joseph Krauskopf and Isaac Mayer Wise. Even the Holocaust has been reconsidered in light of The Origin of Species, in the works of Mordecai Kaplan and Hans Jonas.

Sometimes one puts off reading a particular thinker because of one's preconceptions, and Naftali Levy (1840–1894) is a case in point. Three other studies have been made of this Polish rabbi's Toldot Adam or The Origin of Man (1874),1 and, frankly, I doubted that there would be much more to say. As the earliest known translator of (excerpts of) Darwin into Hebrew,2 and as a correspondent of Darwin, his significance was well established.3 Levy had been presented in the literature as a traditionalist who had sought "to convince the Jewish doubtful that science and Torah were not only fundamentally compatible, but mutually illuminating,"4 and "to show harmony between the Torah and the Darwinian theory of evolution."5 He was said to have used "the discoveries of the new science to demonstrate the veracity of Judaism’s claims of Divine wisdom and to prove the relevance of Torah and Jewish tradition."6

A translation of Toldot Adam has been published online, and half of the sixty-page Hebrew book had been scanned for HATHI (why only half? These things are sent to try us). A cursory glance through these some time ago had appeared to confirm my assumption that Levy would feature in my work as a minor entry, illustrative of a tendency among some nineteenth-century traditionalists to read evolution into the Torah and rabbinic writings.

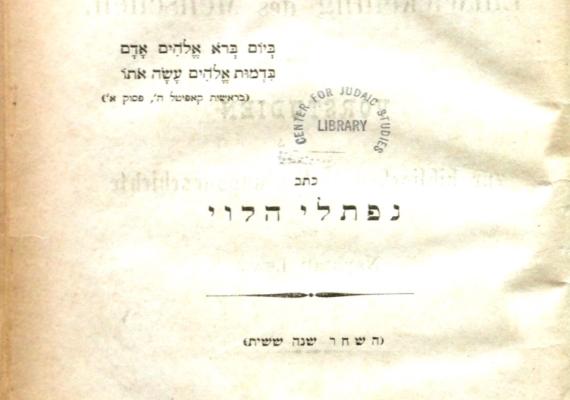

Levy's Toldot Adam is quite rare now and is the kind of book that is confined to rare-book reading rooms. There's a copy in the Cambridge University library, and perhaps seven or eight copies in the U.S. according to WorldCat. This didn't matter terribly, because I didn't plan to spend time getting hold of a copy, since, well, Levy wasn't worth the effort. But after failing to make sense of the translation of one particular argument, I found myself needing to examine the original, which was located, of course, in one of the chapters that were missing from the online scanned version. And so I set about looking for the nearest library that held the book. WorldCat helpfully informed me that the nearest library was only 185 km away. Imagine my delight then, when, on a whim, I checked the local catalogue and discovered that a copy was actually sitting in the Katz Center library stacks. Ten minutes later I was happily turning the pages of the earliest Hebrew translation of Darwin.

What have I learned so far? The author of Toldot Adam was not quite "the faithful, traditional rabbi… definitely orthodox in outlook" portrayed by some.7 Levy did not write again on the subject of science, and it is likely that his stance shifted toward a more cautious position, but there were certainly contemporaries who sensed something subversive about the youthful study, as illustrated by an unfortunate incident in London in 1883, when Levy's former friend, Rabbi Joseph Kohn-Zedek, cited Levy's views on evolution to justify a call for the withdrawal of rabbinic approval that had been granted his later halakhic studies. Most likely the problem had been the tone of the work, which gave the impression that one might not take for granted the authority of received religious tradition over the discoveries of modern science. Levy, who translated at least ten short sections from The Origin of Species for his study, certainly held Darwin in high regard. As he explained,

The knowledge of the existence of life on the earth for thousands of years since ancient times is a result of the application of the theory of "the origin of species" which in our time has provoked sensation at every seat of learning, and on the basis of which natural scientists of our generation continue their [intellectual] ascent. It is vital, therefore, to listen to and read the principal enunciator of this theory, the most important researcher of his generation, Darwin, whose honour fills the scientific world.8

Excited about the underlying reality of nature revealed by science, he exulted that these "sublime matters [were] hidden from the masses of the people."9 It is perhaps this excitement that led him to make speculations uncharacteristic of one espousing an Orthodox religious worldview, such as his remarkable concluding remarks on immortality, ignored by earlier commentators, in which he argues that man will one day evolve to a stage where he will defeat death itself.10 Also, in contrast to other Jewish evolutionists who rejected the apparent cruelty of natural selection in favour of some kind of divine guidance, Levy's God reigned over a natural world undeniably shaped by the darwinian "struggle for existence," or milhemet ha-kiyum, characterised by chance and massive loss of life through predation and competition; in fact, such suffering was viewed by Levy as the primary mechanism by which human morality evolved.11 And then there are the intriguing hints of something more heterodox, still. On one occasion, Levy allows Nature to usurp God:

[A]fter it was all ready, nature [ha-tevah] could give forth the command: Let there be light! This law was achieved, thus: the elements of the entire universe separated into the bodies of the world, namely, the inert matter, the plant and the animal; and after the great law in nature [that is, evolution] fulfilled its aim and its perfection, there appeared the most glorious creation in all of creation… man!12

And at another moment he suggests that the image of an ape-like hominid was a more accurate portrayal of the first man than was the biblical claim of divine likeness:

All contemporary researchers who hold to Darwin's theory will agree that early generations [of humans] were wild and uncivilized… and trace the [human] lineage down to the apes, the forefathers of the perfected man… Thus natural science has enunciated a great theory: that man is a product of [his] environment… And I shall proclaim loudly giving honour to man as a beast of the field; and there will be those who will be shocked at the fact that I correctly read Darwinism in the Torah, and I believe more in his theory than the text which says "Let us make man in our image, after our likeness!"13

If nothing else, then, it'd be a mistake to see the young Levy as a traditionalist offering nothing more than an evolutionary midrash. If not a heretic, he's certainly a rarer species of Jewish Darwinist than I’d first imagined.

[1] Naphtali Levy, Toldot Adam [The Origins of Man] (Hebrew; Vienna: Spitzer & Holzwarth, 1874). Strictly speaking, the work was first published in a well-known Haskalah journal as "Toldot Adam," Ha-Shachar 6 (1874): 3–60.

[2] Levy himself cites German translations of Darwin's writings, including The Origin of Species, of which there were three editions of the German translation by that time, by Bronn (1860, 1863) and by Bronn and J. V. Carus (1867).

[3] Darwin indicated his pleasure in the idea of Jewish engagement with his ideas in his reply to Levy, in conversations with Christian friends, and in his Autobiography, in which he exclaimed that "Even an essay in Hebrew has appeared on it [The Origin of Species], showing that the theory is contained in the Old Testament!" Levy's personal correspondence with Darwin, and Darwin's interest in Levy's work, is treated at length in Ralph Colp and David Kohn, "'A Real Curiosity': Charles Darwin Reflects on a Communication from Rabbi Naphtali Levy," The European Legacy 1.5 (1996): 1717–27.

[4] Colp and Kohn, "A Real Curiosity."

[5] Edward O. Dodson, "Toldot Adam: A Little Known Chapter in the History of Darwinism," Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith 52 (2000): 4.

[6] Michael Shai Cherry, "Creation, Evolution and Jewish Thought" (PhD dissertation, Brandeis University, 2001), 134.

[7] Colp and Kohn, "A Real Curiosity," 1721.

[8] Levy, Toldot Adam, 33.

[9] Ibid., 11.

[10] Ibid., 57.

[11] Ibid., 45–46.

[12] Ibid., 30.

[13] Ibid., 40, 41.