In Memory of an Oxonian Yeshiva Bocher

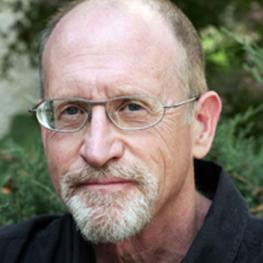

The current issue of JQR features a forum devoted to the scholarly legacy of its past editor Elliott Horowitz, who died last year. Contributions from Horowitz’s collleagues Natalie Zemon Davis, Javier Castaño, and Francesca Bregoli—historians of early modern Jewish culture all—are complemented by one from a journalist and kindred spirit, Stuart Schoffman, in which Schoffman reflects on the meaning of scholarship for Horowitz the man and for Jewish learning more broadly. This post is an excerpt of Schoffman’s piece.

My friend Elliott Horowitz reveled in irreverence. We first met early in the century, when I was a columnist at the Jerusalem Report and he was completing Reckless Rites, his masterwork on Purim and Jewish violence. As Yale-trained yeshivah boys from Queens and Brooklyn and fellow “Anglo-Saxon” immigrants to Israel, we had much in common. We shared a fascination with Jewish history, he as a polished and prolific scholar and I as a fellow traveler. Every second Friday, we would meet for breakfast at a café in the German Colony, or else at Carousela, a student hangout near Elliott’s book-stuffed home on Rehov Molkho. He was a solid Orthodox Jew. He wore a knitted kippah, prayed thrice daily (in a minyan if possible), and drank only kosher wine. But he favored Carousela, meatless and closed on Shabbat, because its kashrut certificate was not authorized by the Chief Rabbinate.

As a specialist in early modern Jewish history (and aficionado of iconoclasm), it suited Elliott well to live on the Jerusalem street named for Solomon Molcho, the sixteenth-century Portuguese converso and false messiah who was burned at the stake for heresy. Some recipients of his emails got a chuckle from his satirical professional signature: “Molkho Institute for Absurdly Abstruse Research,” [an alliterative mouthful also in its Hebrew version, Makhon Molkho Le-chokhmologia Mitkademet.] Others surely found it unfunny; to him it mattered not. ... Nowhere, as I search through thousands of undeleted emails (my bad but useful habit), do I find any sign-off by him as a Bar-Ilan University professor. He taught there for many years, but it never defined (or confined) him. He did not share its priorities. Israeli professors often find refuge in local research centers, but not the nonconformist Elliott: preceding his invention of the Molkho Institute, his emails simply appended, in Hebrew, “I am not a fellow of the Hartman, Van Leer, or Shalem Institutes.”

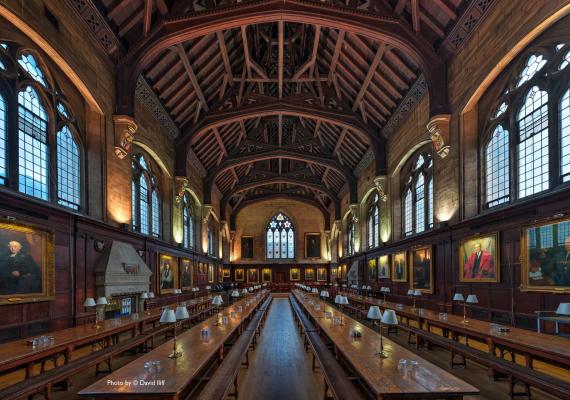

Following his early retirement from Bar-Ilan, he spent three terms at a haven he found more congenial: Oxford’s Balliol College, an academic stronghold founded in 1263, whose men, in the words of a typical alumnus, the British prime minister (1908–16) Herbert Asquith, were graced with “the tranquil consciousness of an effortless superiority.” According to the official Balliol obituary, Elliott was the “Oliver Smithies Visiting Fellow and Lecturer from Trinity Term 2015 to Hilary Term 2016.” ... Now, at last, Elliott could proudly announce his true affiliation in his email signature. But he added a devilish twist: careful readers of the Hebrew transliteration [noted] the eccentric choice of ‘ayin and not alef, spelling the biblical word belia‘al, meaning “evil.” He relished every moment of his too-short time at Oxford, but could not resist—ever the prankster—ironizing it too.

...

Read the rest of Schoffman’s essay remembering Elliott Horowitz via Project Muse with no subscription needed for six months. (The rest of the forum is accessible there with a subscription.)

See also the In Memoriam penned by JQR’s editors.