Q&A: Katz Center Fellow Mary Channen Caldwell on Jewish Music and Musicians in Medieval France

Natalie Dohrmann talks with 2023–24 Katz Center fellow Mary Channen Caldwell about her research on music, conversion, and the global Middle Ages.

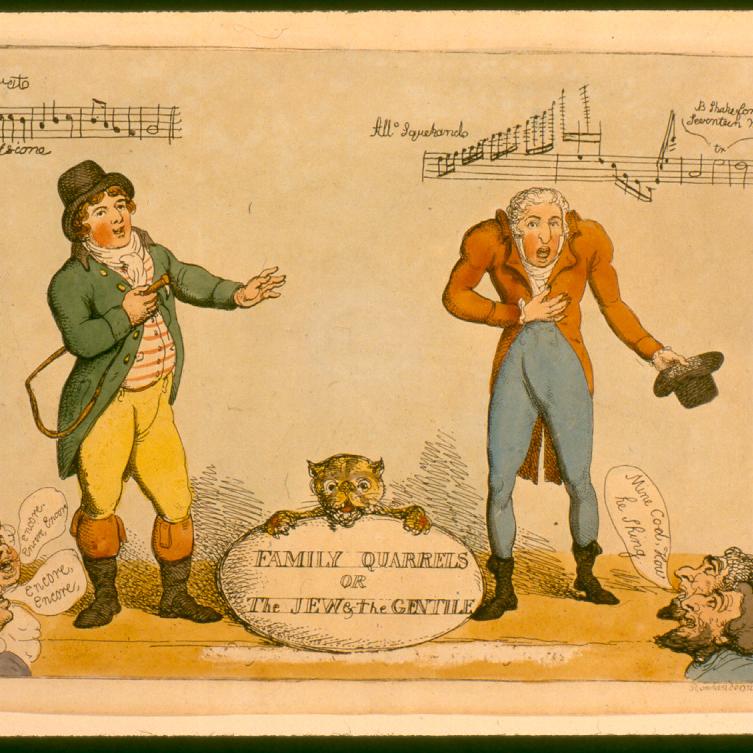

Paris Bibliotheque nationale fonds fr. 844, fol. 175r

Natalie Dohrmann (NBD): Mary, tell us a bit about your scholarly interests and what especially excites you about them personally and/or intellectually.

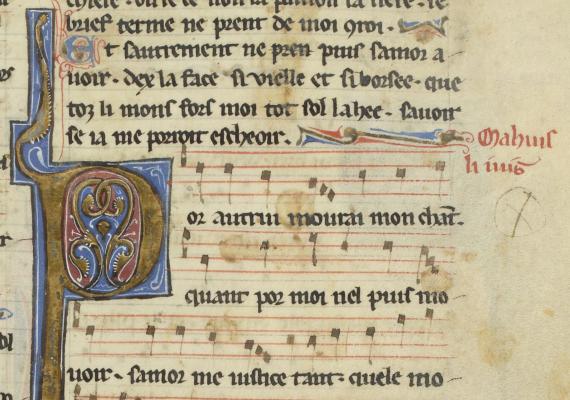

Mary Channen Caldwell (MCC): My research falls somewhere at the intersection of music, medieval history, and religion, with dance and gender studies also significant discourses in past and current work. If one word sums up a lot of what I focus on, it would be song—the linking of melody and text is powerful on many levels and raises many fascinating questions about how and why composers, singers, and listeners conceived of the flexible and variable relationship between these elements. Song as a concept threads its way throughout my earlier publications, especially my first book Devotional Refrains in Medieval Latin Song, which argued that the refrain (a repeated portion of text and/or music, a parallel to the contemporary idea of a chorus) had meaning beyond the formal in devotional song repertoires of medieval Europe, including engaging in the interpretation of sacred temporalities, the formation of communities, rituals of reworking, and multilingual song writing. In the book I ask, “What does the refrain do?” Ultimately, I argue that it does an awful lot, much of which has been overlooked by musicologists because it is so simple—refrains are often short, they repeat, and they are frequently connected to less sophisticated song genres. But there is complexity in simplicity, as my research shows, and connection to the devotional lives of men, women, and children.

Song continues to be an anchor for me. I’ve explored the resonances of song in mystical practices, in the medieval schoolroom, in relation to devotional dance, as part of epistolary traditions, and as a site of creative reworking and borrowing. In my current book project on the musical hagiography of the medieval St. Nicholas of Myra (more popularly known as the precursor to Santa Claus), song is central to how medieval Christians (and occasionally Jews and Muslims) venerated this insanely popular saint. As a fellow at the Katz Center this past academic year (2023–24) on the theme of Jewish sound and music I’ve also begun exploring the boundaries of Latin and Romance song repertoires in medieval Europe by considering overlooked and understudied connections between Jewish (Hebrew) and Christian (Latin and French) song.

NBD: What about your work in primarily Christian music history drew you to want to be part of the Katz Center cohort? Has your participation this year left an imprint on your own scholarship?

MCC: My research focuses predominantly on religious musical practices, and the role of the devotional, the spiritual, the mystical, and the liturgical has long been interesting to me. I am always keen to better understand how people understand music to function within their own religious practices and what value they see in music as a medium of expression that does something not accomplished in other media. When I heard about the theme for the 2023–24 fellowship year, I knew I wanted to be involved in some way and was grateful to have been chosen as a Penn Faculty Fellow since my work has not historically engaged with Jewish studies. I'm very glad the center took a chance on me!

The amazing thing about being a fellow is that it pushed me beyond my comfort zone within religious studies focused on Christianity and encouraged me to begin learning about Judaism from a historical and contemporary perspective. This led to my project for the year on song that moves between Jewish and Christian contexts. The research for this included working with and learning from many Jewish studies scholars, including historians, literary scholars, and music scholars, both within the fellowship and from the wider scholarly community. I forged so many new connections and have learned a lot; I even started learning to read Hebrew and am working with a few medieval Hebrew manuscripts, which has been really difficult but very rewarding.

NBD: What is “contrafacture”? How prevalent is it in music? And why is it such a resonant concept?

MCC: Contrafacture (you’ll hear people refer to contrafactum, contrafacts, contrafacta, even musical reworking, borrowing, adaptation, quotation—there’s not much agreement on the terminology) refers to the reuse of melodies with different texts. One well-known example is the melody for the children’s song “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” which is sung to a French tune, “Ah! vous dirai-je, maman,” popularized by Mozart in a set of variations and also used to sing the “Alphabet Song” and “Baa, Baa Black Sheep.” So, through contrafacture, the original French text is removed, and we sing a number of different texts to the same melody.

Contrafacture is massively important within the history of music globally; the recycling of melodies happens in many different musical and cultural traditions. Within my own work I have examined the relationship between languages when melodies are contrafacted, and most recently as a Katz fellow, between Hebrew and Old French specifically. As the fellowship year made clear with many fellows examining contrafacture (for example, Hadar Feldman Samet, Oren Cohen Roman, Michael Lukin, and others) contrafacture is absolutely central to Jewish music history. This was even a theme in the end of year conference this month on a roundtable titled “Acts of Musical Duplication.”

The concept continues to fascinate historians and music scholars because it has the potential to connect really disparate musical domains—for instance, in my own work, contrafacture links secular French song of thirteenth-century France with devotional Hebrew Shabbat songs. This is the case even very recently with examples raised by fellows and guests at the conference of popular songs that survive with devotional Hebrew or Yiddish texts that make the (secular) popular songs more appropriate for performance within more conservative communities.

NBD: You are contemplating a book that takes “conversion” as a trope and way to talk about a range of interrelated cultural phenomena from actual religious conversion, to movement of melodies from secular to religious realms, of lyrics between languages, and even the depiction of conversion in melodic forms. Can you tell us more about what the idea of conversion might reveal about musical and social history of the Middle Ages?

MCC: I’m hoping it will reveal a lot about music and culture in the Middle Ages! But I don’t know quite yet. When I began researching my project of this fellowship year on intersections between Jewish and Christian musical practices in medieval Europe, I was struck by the fact that conversion was such an important aspect within historical and literary studies of the period, but music studies had not yet considered what role music might play. This is not true for later periods, when the intersection of music and colonialism brings conversion (forced and coerced conversion especially) to the foreground; this is an area that has ample musicological scholarship and is really rich and interesting. But for the premodern period there is little reflection on how conversion might function within musical contexts, as a metaphor within musical practices, or even in missionary practices in the precolonial period. We know that music was heard when Europeans went on crusade, for example, and we also know that converts between religions sang and made music, but we know little about how conversion was framed in relation to music, and this is what I want to look at in my future research.

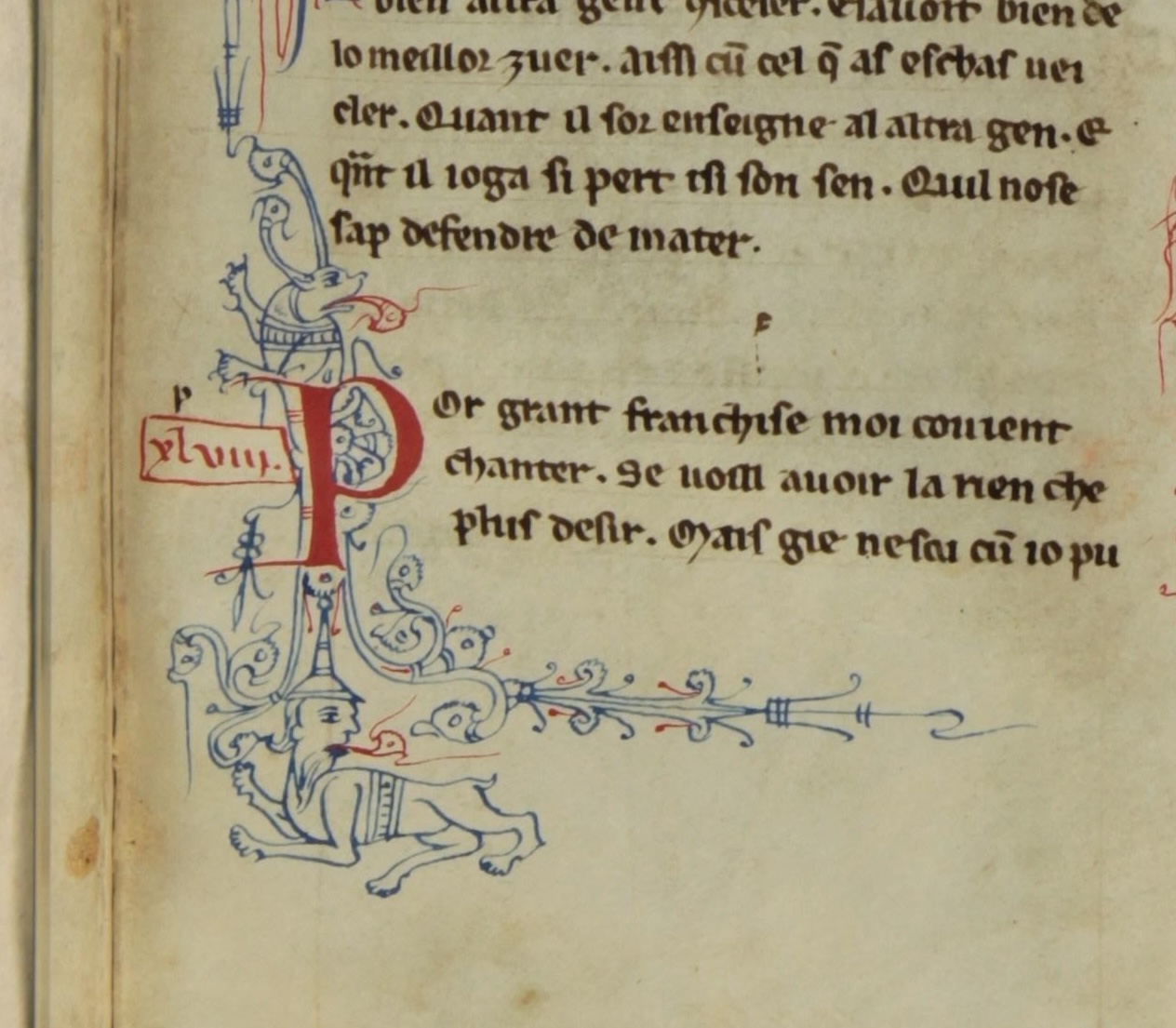

At the moment, I plan to take a capacious view of conversion that includes, for instance, conversion within a single religion (from simply Christian to even more Christian, or between Eastern and Western churches); representations of conversion in plays and songs; inner conversions (such as the “conversion of man” trope in Latin song); and many other forms of conversion that expand our understanding of the term in fruitful and interesting ways. I don’t know what sorts of conclusions I’ll be able to draw, but I have no doubt that it will be a deeply stimulating topic with many possible avenues. Already in the project I developed this year on music and conversion in northern France in the thirteenth century, I have been able to interrogate the identity of a Jewish trouvère (singer-song writer) and examine material traces of how music is converted from one religious sphere to another in thirteenth-century Hebrew devotional books.

NBD: You have been on the forefront at Penn of scholars thinking about the “Global Middle Ages”—can you say more about what this is, what it comes to correct, and how it is enlivening or altering your discipline?

MCC: Forefront is definitely an exaggeration! I am however involved with and committed to Global Medieval and Renaissance Studies here at Penn, a wonderful program that includes a minor for undergraduates, a certificate for graduate students, a publication, awards, and many other activities. In my own teaching I have looked for ways to be more geographically inclusive, offering seminars for graduate students like “Music and Sounds of Difference in the Global Middle Ages” in 2021 which considered musical practices from not only Europe, but also Ethiopia, the Middle East, and Japan, amongst other places. I also seek in all my courses as much as possible in recent years to move past the disciplinary sticking place for early music within a Christian framework, considering the ways in which other religious practices in the Middle Ages engaged with music for worship and entertainment.

The move toward a global Middle Ages continues to be influential within music studies and helps to bring together diverse scholarship (and scholars) that might not previously have been in the mainstream. I know that undergraduate and graduate students here at Penn are attentive to the value of studying a Middle Ages that pushes outside the boundaries of Europe, and I hope to see many more students tackle the challenges (ones of language, source material, and access) of global historical projects. It’s really hard, but valuable, and to use your term, it truly is enlivening the field.