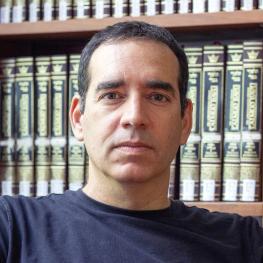

Katz Center Fellow Ofer Ashkenazi on German-Jewish Film, Photography, and Culture

Katz Center Director Steven Weitzman sits down with Ofer Ashkenazi, a current fellow whose research seeks to shed light on otherwise unuttered, or under-examined, perceptions of Jewish domestic experiences under Nazism.

This blog post is part of a series focused on the research of current fellows. In this edition, Katz Center Director Steven Weitzman sits down with Ofer Ashkenazi, whose research seeks to shed light on otherwise unuttered, or under-examined, perceptions of Jewish domestic experiences under Nazism.

Steven P. Weitzman (SPW): Before I ask you about your current work, Ofer, I wanted to spend a little time exploring the sources of your intellectual interests; one of these is German-Jewish visual culture, including film. Can you tell us a little about what led you to that, and can you give us a taste of what your research into German-Jewish film, in particular, has revealed?

Ofer Ashkenazi (OA): I must confess that I did not plan on studying Jewish visual culture. Quite the contrary, when I started graduate school, I was intrigued by the collapse of the Weimar Republic and the rise of National Socialism. Self-confident and utterly clueless, I set off to solve the mystery of Germany’s “special path” by looking at the most popular genre films of the time. I was impressed by Siegfried Kracauer’s captivating explanations for the success of Nazism, which portrayed Weimar films as a display of the German “psyche” and its pathologies. However, after watching (and re-watching) numerous films, and after reading abundant contemporaneous reviews and related essays, I arrived at an opposite conclusion: these films—popular and often critically acclaimed—propagated progressive ideals. As such, they complicated and resisted conventional explanations for Weimar’s demise.

It was only a couple of years after I finished a book based on this research when I first realized that, almost with no exception, all the films I wrote about (and many more!) had Jewish producers, directors, set-designers, scriptwriters, music composers, or main actors. Moreover, the critics who wrote about them were often Jewish, and they published their reviews in newspapers and magazines that had Jewish editors or publishers. My second book, Weimar Film and Modern Jewish Identity, takes the over-representation of Jews in the pre-1933 film industry as a starting point. It argues that many of the most popular genres films of 1920s Germany—domestic comedies, melodramas, horror, war, and adventure films—often negotiated the Jewish experiences of their filmmakers. “Jewish” here has little to do with the religious or cultural heritage of Judaism. Instead, it indicates a particular social position, of an outsider who seeks to integrate with mainstream (bourgeois) society without fully giving away her or his difference.

This aspect of German national culture seemed all the more fascinating for me when I looked at the role of Jewish filmmakers in the formation Heimat-culture. Heimat, the provincial German landscape that allegedly display and host the inherent, unchanged national traits, has been a fundamental trope in modern German culture. Heimatfilm is considered to be the only genuinely “German” genre; during the Nazi years it propagated the idea of an ethnically homogenous Volksgemeinschaft, and during the Cold War it presented an “apolitical” haven, where German-inflicted atrocities have been forgotten. My recent book, Anti-Heimat Cinema (forthcoming 2020), suggests that, between 1918 and 1968, Jewish filmmakers both laid the foundations of this genre and appropriated its clichés to criticize German nationalism. Their subversive use of Heimat imagery predated, and evidently inspired, the German counter-culture in the aftermath of 1968, when the “New German Cinema” utilized similar methods to criticize the German national ideologies of the late Cold War era.

SPW: Your current research here at the Katz Center focuses on domestic photos taken by German Jews in the period leading up to the Holocaust. Can you tell us about this project, and what you are seeking to learn from it?

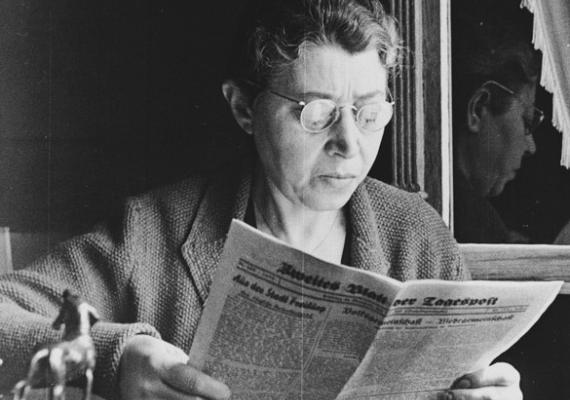

OA: I am interested in Jewish “vernacular photography” under the Nazi regime, namely photographs that were taken by non-professional photographers, and which documented their living environments and daily routines. By the early 1930s, many German-Jewish families had avidly used pocket-sized cameras to document their everyday experiences. I argue that, gazing at a rapidly changing environment after January 1933, amateur Jewish photographers did not utilize their cameras to merely document, but also to reflect on the new reality, to make sense of it, and to reclaim agency in it. My analysis of the photographs underscores their dialog with the visual imagery of the time, in particular the photographers’ (conscious or otherwise) effort to restage familiar iconography outside of its original context. The photographs I study, however, were normally embedded in a larger collection, mostly in albums, which narrated the documented experiences, negotiated their meanings, and sought to construct their place in the shared memory of the historical moment they recorded. My analysis therefore places individual photographs within the context in which they were displayed and acknowledges their role in the narrative of the album. As such, these photographs provide us with a unique case of “ego documents,” which reflect on experiences close to the time of their occurrences. In comparison with other types of “ego documents” of Jews under Nazism, however, photographs are abundant and represent a much broader variety of narrators, including children, young women, orphans, working-class families, etc. A careful analysis of tens of thousands of such photographs—available in numerous archives and private collections—provides us with an exceptionally rich source for the study of Jewish experiences in Nazi Germany: of the various ways Jews perceived the new reality, sought to understand it, and also sought to confront its implications.

For Jews in Nazi Germany, “home” had indicated a few specific connotations that complemented, and sometimes obscured, its traditional functions. As the pressure on Jews intensified and their access to public places had been increasingly restricted—from working places and city parks to vacation resorts—"home” became a shelter from the outside reality, as well as a place where isolation and displacement was experienced. Home was the place where the feelings of belonging to German (mostly middle-class) society and culture could still be exhibited and celebrated; it was also the place where helplessness was expressed, alongside new self-perceptions and new hopes for the future. Finally, home was increasingly a place left behind, or a place soon be left behind: either by emigration or through forced migration to other houses (smaller and often designated as “Jewish homes”). Amateur photographers captured these particular functions of home. Through photographs of their homes, they reflected on the abovementioned experiences, negotiated their fears and aspirations, and manifested their comprehension of the changes they endured. In many cases, they sought to use photographs to gain control over the ways their experiences would be remembered in later years. When I look at the photographs, and at the roles they played in family albums, I seek to unravel the emotions and ideas they manifest and thus to understand better the experiences that gave rise to these photos and made them important to the family narrative.

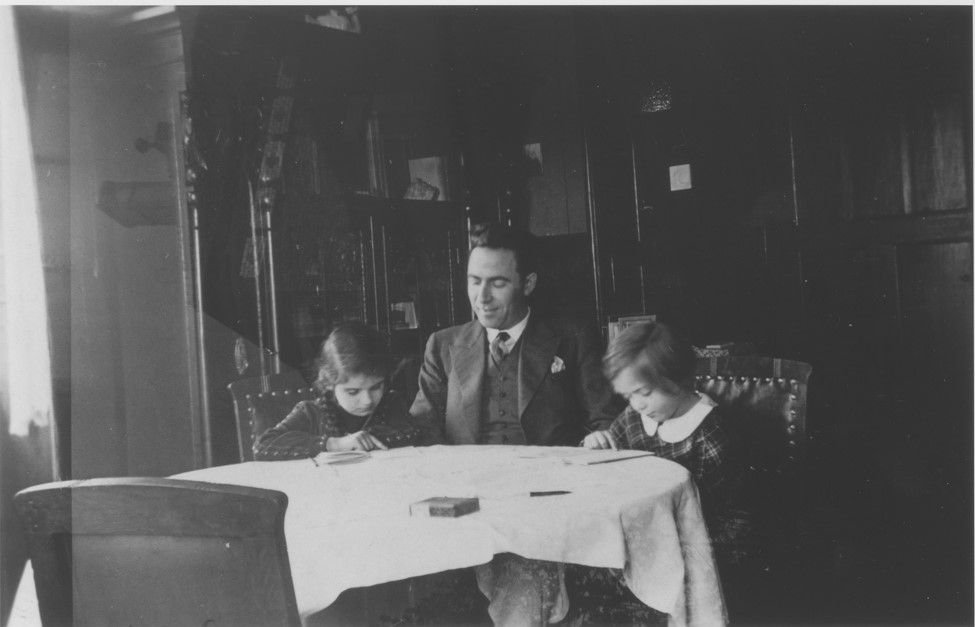

SPW: Can you offer us an example of such a photo? What can you learn about domestic life or about the role of photography as part of German-Jewish culture through this image?

OA: Take, for instance, the following photograph of the Kleeblatt family from the village of Salder, in the vicinity of Brauschweig. The caption of the photo in the album labels it as the family’s “last photograph” of their home in Salder. The reason for the “photographic event” is their forced departure, because of the family’s Jewish background. Yet the image itself discloses no “Jewish” elements and, instead, its arrangement highlights a mixture of local, national, and class identities. The photograph is framed in a way that would allow us to see the generic Heimat-scenery painting on the wall, which was a common element in middle-class homes in Germany (a cliché symbol of affiliation with bourgeois culture and with the German homeland). In addition to the visible furniture—in this case, typical of the middle- and lower-middle-class German families—the photograph underlines the insignia of Braunschweig (the lion on the curtain). As the three generations squeeze together at the center of the image, the insignia seems to be part of the family, almost as though it is one of the “faces” returning the camera’s gaze.

The “last photograph from Salder” thus condenses various aspects of modern Jewish identity in Germany, including a documentation of the process of exclusion (it is the final page of an album that otherwise celebrates Jewish integration in Germany), the identification with national and local iconography, and the emphasis on multi-generational continuity. More than adherence to a German nationality, therefore, such an image of the Jewish home manifested the longing for a complex, multi-layered notion of Jewish identity in modern Germany.

SPW: I am intrigued by your ability to “read” photographs, to draw insights from between their lines. How is the way you view a photograph different from someone without any scholarly expertise in the interpretation of visual culture?

OA: When historians work with written texts, they distinguish between explicit and implicit aspects of it, and try to follow (stated and veiled) references that the text uses to make its point. Consequently, they endeavor to situate the text in its social, cultural, and intellectual contexts, in order to assess its functions in or intentions vis-à-vis the historical reality in which it was produced and read. When I work with images, I ask the same questions to reach a similar goal. When we think of the image I mentioned above, for instance, the explicit elements are the caption (“last photograph”), the identifiable family members, and the place, the family home. The implicit elements that the photo displays, however, go much further: they exhibit what “home” means for these people; what the relationships are between them; what emotions are at play here; and what the meaning of being German Jews is for this family in 1938. We can decipher at least some of these questions by looking at the references that the photograph “quotes” here: the Heimat-cliché painting, the Brauschweig insignia, the type of furniture and clothes they see as “theirs,” etc. Each of these “quotes” has particular connotations in the culture in which they live (and want to be seen as part of).

My reading looks at different elements of the picture and asks, where have I seen this before? What can be the meaning of the photographer’s choice to include specific iconography within this photograph? The only premise I have to make is that the choices that were made in these photographs do matter: the perspective of the gaze, or the framing of the image (what it includes); the arrangement of the people in it; the use of depth and light; the inclusion of familiar imagery (Heimat); and so on. I do not have to assume that the photographers—and the people in the photo, and the people who kept it in the album—were aware of all the meanings that are “echoed” in the photo. Oftentimes they captured an image and included it in the album because it conformed to aesthetic and thematic conventions of the time. I would argue that, in particular cultures, these conventions have attachments to ideologies, power structures, identities, and memories; and the adherence to, or deviation from, such conventions is significant, whether or not it was based on a conscious decision. Of course, this is not different from the premises historians have in mind when they approach written texts.