Travel Documents before Modern Passports

Passports and visas are part of the familiar apparatus of modern day travel, essential for maintaining the boundaries of the sovereign nation state. How did individuals cross borders in the past? Early Modernity—a time of heightened mobility—marks the period in which travel documents come into widespread use. During the late fifteenth century political authorities began to demand that all travelers carry documentation. Unlike modern day passports or visas, which are issued by a nation state, early modern travel documents (often referred to as “safe conducts”) were issued by the authorities of a particular region. Travelers carried these documents and showed them to the guards posted at the border, to prove that the bearer had permission to travel within a given area.

In addition to their value for understanding the day-to-day realities of early modern travel, such documents can help us understand how people understood membership and state, minority-majority relations, and more. Yet the paperwork that enabled people to travel from one region to another remains relatively unstudied. One reason for this is that such documents were ephemera, useless to the bearer after their period of validity, and thus haven’t survived or haven’t sparked historiographical attention. But among the papers of the Worms Jewish community in Israel’s Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People I uncovered several examples of these geleiten (“safe conducts”), used by Jews to pass through the Electoral Palatinate, one of the territories of the Holy Roman Empire, and they sparked my interest.

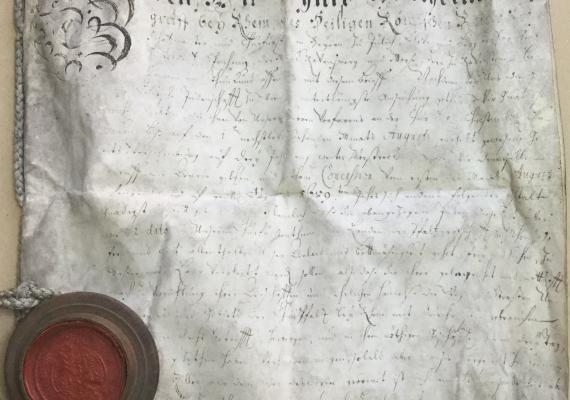

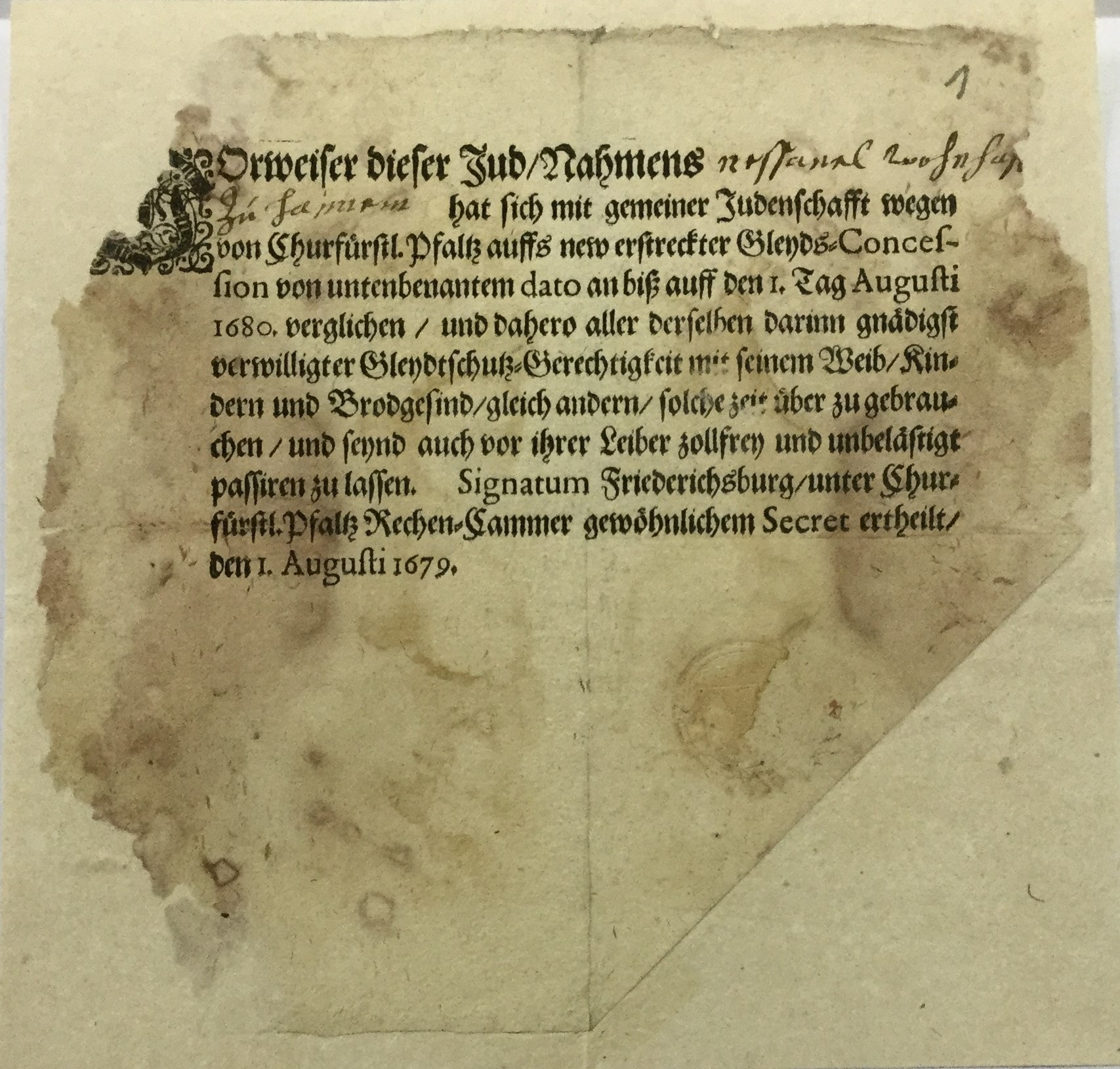

In the current issue of JQR I examine these passes and their use. The ones issued to Jews differed from those issued to individual Christians in that the Jews of Worms paid a flat tax to the Elector, in exchange for which all Jews received the right to travel. The document granting Jews the right to travel was a large, multipage document, to which the large wax seal of the elector was affixed. Of course, individual travelers couldn’t carry such a document. Instead, this communal “privilege” was locked up along with other important papers belonging to the community, and individual travelers purchased Tachengeleiten, pocket-sized preprinted documents, subsequently filled in with the traveler’s name. Tachengeleiten were only valid for one year, and most travelers likely disposed of them after that time. These small sheets of paper, and the multiple communal records documenting their use, shed new light on the individual mechanics and communal dynamics regulating how early modern Jews traveled.