Tobit’s Dog: Short Form Scholarship

In fewer than 200 words in the journal’s third issue, Israel Abrahams made a mockery of a long beloved motif of western art, scriptural interpretation, indeed Scripture itself, when he informed the reader—summarily, and without footnotes or citation—that pseudepigraphical Tobias did not have a dog! (JQR 1.3 o.s. [1889]: 288)

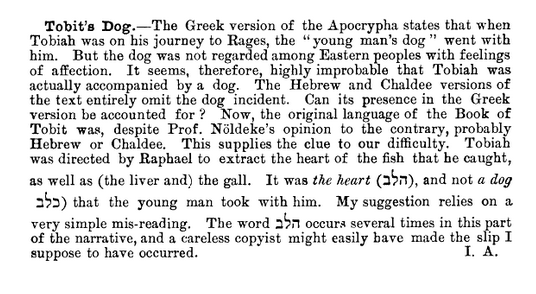

The dog appears in Tobit 6:2 and 11:4, accompanying our hero in his quest to gather materials with which to exorcize his possessed beloved. But it is in fact a solecism, the perdurable product of a rather clumsy copyist’s mistake. Instead of loyal canine (kelev), what Tobias had with him on his walk was a fish’s heart (ha-lev). (Easy mistake to make, we make it all the time.) Along the way he casually undermines Prof. Nöldeke and asserts the Semitic origins of the preserved Greek work. Quod erat demonstrandum.

The short scholarly “note” was a ubiquitous genre in early JQR. In volume 4 no. 3 (1892) alone, there are no fewer than seven authored notes between pages 498 and 512: an addendum to a published bibliography of Graetz, a foray into the pronunciation of the letter ‘ayin, a report of a fourteenth-century rumor about the ten tribes, and more. They are tasty orts of erudition, but not enough to sustain a whole article. The stuff of the early “note” is the sort of wonderful discovery that distracts us daily from our main topic of research. The little “aha!”s that cause us to look up and relate the revelation to our spouse and then jot it in a margin soon to be lost, or the “oh, no!”s in a response to a nagging error or omission in published scholarship.

Sometimes a scholarly finding needs only 3500 words to express itself fully; others want 18,000. Yet the field makes little space for idea arcs of these length. In such cases, conforming to the 10K-or so-word article standard happens through padding or amputation. Though the editors have continued to resist the long, law-review length essay, readers of the current JQR will know that we have sought in our own way to resurrect short form scholarship. Though we have failed to-date to achieve the pith that Abrahams has here (he reduces even his own name to initials) we find great opportunity in playing with scholarly genres that get to the point.

The note in JQR serves many functions. At times a note represents an learned aside à la Abrahams; but others nod aspirationally to Solomon Schechter’s sparkling essays. Some are delivered in the form of the review essay, which we find generally more substantive than reviews of single books. Our forums are collected notes on a shared theme, gathering essays of anywhere between 1500 and 4500 words into a single conversation. Ideally, each of these genres makes space for the scholar to be an intellectual.

We are also opening a new subset of the note devoted to Jewish letter-writing. Inspired by our two-part forum on the correspondence of Jewish intellectuals (JQR 107.3 and 108.1), we invite one-off essays that engage a significant letter or epistolary exchange amplified by some sparkling commentary or contextualization.

The best short form piece is readable and provocative, erudite and expansive, and is in some ways the forerunner of the blog post, but with more heft and staying power. We do not see short form scholarship as an accession to the attention spans of the internet age, but rather as a celebration of the excesses of research, the overflow of the archive, the footnote given its day in the sun, and the connections made possible when academics’ minds are given a bit of freedom to roam.

The current editors have used the short essay to mark their inaugural issue (JQR 94.1 with essays by Daniel Boyarin, Suzanne Last Stone, R. B. Kitaj, Jeffrey Shandler, and others) and to celebrate our hundredth birthday (JQR 100.4 with pieces by Galit Hasan-Rokem, Moshe Idel, Daniel R. Schwartz). Peruse our tables of contents, beginning in the 19th century, and moving until our current issue (JQR 108.3) for an extraordinarily wide range.

Happy reading.