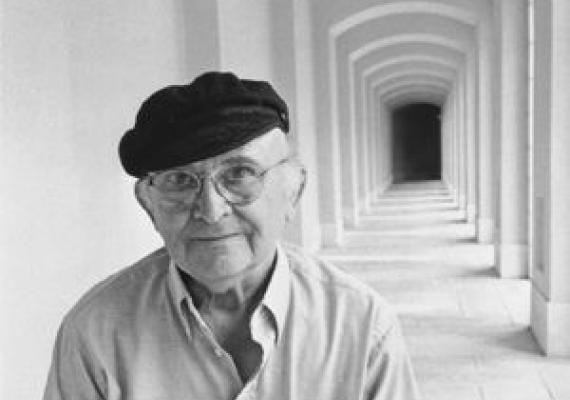

Remembering Appelfeld

The Israeli author Aharon Appelfeld died on Thursday, January 4th. One of the most important authors of the twentieth century, his works reached far and wide, translated into dozens of languages. Appelfeld was among the founders of Israeli literature, one of a handful of writers like A. B. Yehoshua and Amos Oz, who, in the 1960s, shaped Israeli literature for the many decades that followed. Appelfeld’s fiction, however, was different from that of the other members of his literary generation, the “Generation of the State” (so dubbed by the great scholar and critic Gershon Shaked), for it drew on his experiences during the Holocaust, and was nourished by his idiosyncratic creativity.

Appelfeld was born in Czernowitz in Bukovina (now Ukraine) in 1932. When we first met, I told him that my mother was also born there, and ever since, he always introduced me as “bat ‘Iri”—“a daughter of my town.” When I told him of my plan to write about my own hometown, Haifa, he said in his melodic soft voice: “but Nili, why don’t you write about Czernowitz?” In 2011, Appelfeld came to Penn to participate in a conference I organized in his honor. (Click here to see a JQR forum inspired by that colloquium.) In the public interview that I conducted with him at the culmination of the event, his voice cast a spell on all who were present. Now that voice is no more.

Appelfeld’s formative years were spent in the thick of World War II. He was eight when his mother was murdered. He and his father were taken to the ghetto, and from there to a labor camp, from which he escaped. Still a child, he then survived alone in the forest. Yet he rarely described the horrors themselves, but rather remained at the margins of those experiences, writing about the years that preceded or followed the “big bang” in places that barely touched the abyss. His works were branded by the Holocaust, but he wrote in a whisper, so to speak, his muted scream reverberating in both his speech and in his books. The critic Yigal Schwartz, who also edited 28 of Appelfeld’s books, wrote in Haaretz last week that he “saw the world through the eyes of a child running away in the forest.”

Appelfeld came to Israel as a teenager in 1946 not knowing any language well. He served in the army and then embarked on the study of Hebrew as well as Yiddish at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He started publishing poetry in 1956. After having been rejected by a number of publishers, his first book of stories, Smoke, came out in 1962. In the climate of Israel at that time, stories of Holocaust survival were not embraced. He himself said in a 2015 interview, “everywhere it was written ‘Forget,’ and I wanted to remember.” Since Smoke, he has written nearly fifty books, almost all of which deal with World War II and Europe in some way or another. Appelfeld’s novels Badenheim and Katerina were among his most famous works, and were widely translated and garnered him rare acclaim. His last book, Wonderment, came out just last year.

Appelfeld won many literary prizes, the most prestigious of which is the Israel Prize. He was an impressionistic, lyrical, understated artist who honed every word. His fictional world was often distant from the Israeli reality. “Appelfeld’s importance is so significant because he created a different route in the tradition of the Hebrew fiction that began in the 1960s. He is the one who continued the tradition of Bialik’s generation,” said Shaked. In turn, Appelfeld enabled the writings of great authors like Yoel Hoffmann and David Grossman. He himself was influenced by Brenner and Agnon, but he said that Kafka’s works offered vital assistance to those, like him, who wanted to tell about the Holocaust. “Kafka gave us back the words,” he said. “If not for him, it is doubtful that we would be able to retrieve even one word from the depths.” Indeed, if anyone has succeeded in retrieving words from the depths, it is Appelfeld.