Three Generations of Judaic Scholarship

When asked to introduce two distinguished scholars, Ismar Schorsch and Mirjam Thulin, at the symposium on Solomon Schechter in March, I thought about how these two speakers represented very different generations of German-born Judaic scholars. Schorsch, who came as a child to the United States and earned all his degrees here, represented the tail end of the nineteenth-century Wissenschaft des Judentums and its flowering on the shores of America—a process that had begun, well before the rise of Hitler, with Solomon Schechter's move from Cambridge to New York in 1902. Thulin, who was raised as a Protestant in late twentieth-century Germany, where she developed an interest not only in Jewish studies but also in the tangled history of the field itself, represented the more recent rebirth in Germany of Judaic research at levels rivaling its pre-Holocaust achievements.

But what did all of this have to do with me, an American-born baby boomer belonging to the generation between those of Schorsch and Thulin? Admittedly, my own parents, like theirs, spoke German. Furthermore, I was honored to be one of Schechter's successors as an editor of the Jewish Quarterly Review. But then I remembered that my first contact with the name of Solomon Schechter had come during my first years of primary school, when for slightly over a year I studied at the first school named for him, the Solomon Schechter School of Queens. At the lunch preceding our conference I asked my fellow boomer Shuly Rubin Schwartz, who had grown up in Long Island, whether she had also been at that school. Shuly, now a dean at the Jewish Theological Seminary, explained that although her father was a Conservative rabbi she had been sent to an Orthodox day school, since the Schechter School in Queens was too far away. In my introductory comments at the conference I related the circumstances that later led my father—who was neither Conservative nor a rabbi—to move me from the Schechter School to an Orthodox school as well, reflecting a desire for a more rigorous approach to Jewish textual literacy, and I asked rhetorically whether Schechter would have approved.

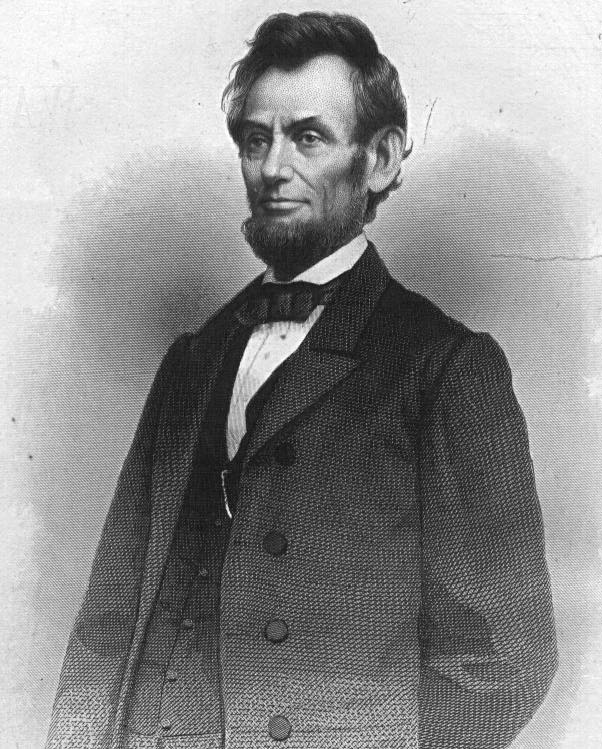

The fragmentation of American Jewry into movements was an issue that preoccupied Schechter, as was the relationship of American Jewry to the core textual and legal tradition of Judaism. Shuly’s own presentation at the symposium later that afternoon discussed an essay on Abraham Lincoln that Schechter originally delivered as a lecture in 1909 marking the centenary of Lincoln’s birth. Noting that the essay may be “the most symbolic” of Schechter's “deep and abiding relationship to America,” she linked it with Schechter’s own struggle over an endangered union—that of American Jewry—which was then precariously split between the Reform movement, centered in Cincinnati, and the nascent Conservative movement, with Orthodoxy still representing only a slim slice of the pie. “When he recounted Lincoln’s ‘pleading with his friends and foes that there is no hope for Americans to live outside of the Constitution if they cannot any longer live in it,’” she suggested, “one cannot help but hear Schechter’s bitterness at the disregard for Jewish law evidenced in his Reform colleagues.”

The fragmentation of American Jewry into movements was an issue that preoccupied Schechter, as was the relationship of American Jewry to the core textual and legal tradition of Judaism. Shuly’s own presentation at the symposium later that afternoon discussed an essay on Abraham Lincoln that Schechter originally delivered as a lecture in 1909 marking the centenary of Lincoln’s birth. Noting that the essay may be “the most symbolic” of Schechter's “deep and abiding relationship to America,” she linked it with Schechter’s own struggle over an endangered union—that of American Jewry—which was then precariously split between the Reform movement, centered in Cincinnati, and the nascent Conservative movement, with Orthodoxy still representing only a slim slice of the pie. “When he recounted Lincoln’s ‘pleading with his friends and foes that there is no hope for Americans to live outside of the Constitution if they cannot any longer live in it,’” she suggested, “one cannot help but hear Schechter’s bitterness at the disregard for Jewish law evidenced in his Reform colleagues.”

Another generation of Judaica scholars, let me add in conclusion, fits squarely between Schorsch and Thulin—those, like myself and Shuly Rubin Schwartz, who were born in postwar America and benefited from the boom in Jewish education taking place during those years. We have, in our own ways, engaged the very issues that so concerned Schechter in his adopted country, and some of us have carried those issues to our own adopted countries. We have learned, as did Schechter before us, that scholarship and life are irrevocably intertwined.