What Do You Know? Sephardi vs. Mizrahi

In the series What Do You Know?, we feature scholars’ answers to questions about Jewish history and culture submitted by our readers.

An anonymous reader asks,

“What is the difference between “Sephardi” and “Mizrahi”?”

Current fellow Dina Danon answers:

Although sometimes used interchangeably, the terms “Sephardi” and “Mizrahi” refer to two distinct Jewish diasporas, each one itself characterized by significant internal cultural diversity. Despite many divergences, having inhabited numerous polities in different circumstances over the ages, these groups also shared important characteristics, including some religious rites and customs. Additionally, since a majority lived for many centuries in the Islamic world, both “Sephardi” and “Mizrahi” Jews encountered the modern age facing many of the same forces, among them Western colonialism, the dissolution of empire, and the rise of nation-states.

Sephardi

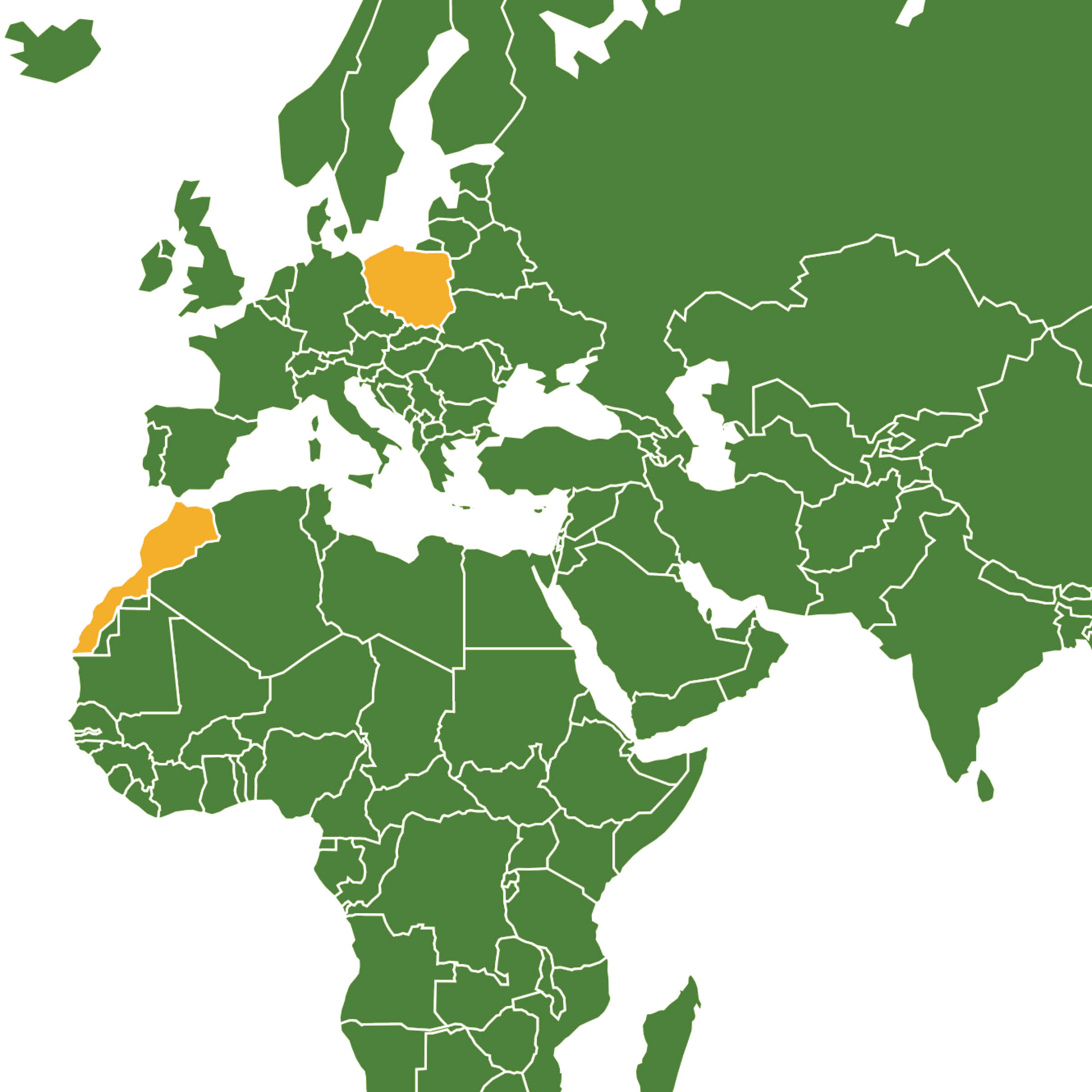

First appearing in the Book of Obadiah 1:20, the term Sepharad came to be linked to Hispania, the Latin word for Spain. The presence of Jews on the Iberian Peninsula dates back to the Roman period, and medieval sources confirm that Jews indeed used to word Sephardi to refer to themselves. While living under Islamic rule, Sephardi Jews participated in the intellectual, artistic, and scientific achievements of the ninth and tenth centuries, a period that would later be termed a “Golden Age.” With the conquest of Spain by Christian forces, a centuries-long process known as the Reconquista, the position of Sephardi Jewry was destabilized, as the community faced increasing hostility due to efforts of the Church to eradicate heresy. After over a century of physical violence, forced baptisms, and disputations, in 1492 this hostility culminated in the Edict of Expulsion, which gave the Jews of Spain the choice to either convert or leave. The last and largest expulsion of Jews from Western Europe of the period, 1492 gave rise to multiple Sephardi diasporas. A majority of those choosing exile migrated eastward toward Ottoman lands, where they settled in cities such as Salonika, Istanbul, and later Izmir. A smaller group opted for Portugal, where they were forcibly baptized only five years later and migrated as “New Christians” in later years to cities such as Amsterdam, London, Bordeaux, and Hamburg. Still others chose North Africa, most notably Morocco, where they developed a dialect called Haketia. While Sephardi Jews reconstituted their communities in disparate locations, they experienced particularly marked longevity in Ottoman lands, where a relatively tolerant environment allowed them to maintain group cohesion. The eastern Mediterranean became home to vibrant Judeo-Spanish culture that flourished there until the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire.

Mizrahi

Meaning “Eastern,” the category “Mizrahi” is a more recent phenomenon. It collapses into one catch-all term numerous Jewish sub-cultures from across the Middle East, North Africa, and central Asia, some of which date back millennia. As it is typically employed, it encompasses communities as diverse as Farsi-speaking Persian Jews, Arabic-speaking Jews of the Maghreb (western north Africa) and the Mashreq (areas east of the Mediterranean Sea), and Berber-speaking Jews of the Atlas Mountains of Morocco, among others. As a classification, the term came to prominence in the early years of Israeli statehood, when Jews from these regions were described as ‘edot ha-mizrah, or “communities of the East.” This terminology was undergirded by an ideological preoccupation with the supposed “backwardness” of the “Orient.” A mere glance at the world map reveals that the categorization of Moroccan Jewry, for example, as “eastern” on the part of Jews descended from Russia and Poland is ultimately much more about a certain cultural geography than anything else. By the 1980s, mizrahim came to displace ‘edot ha-mizrah, as scholars believed it highlighted the social realities of Israeli discrimination against these communities, while activists had begun to appropriate the term and construct a new identity around it. More recently, some scholars have called for the usage of the category of “Arab Jew.” While not applicable to many different “Mizrahi” populations, it nonetheless underscores how the term “Mizrahi” was a product of a false binary between “Jew” and “Arab” that was presupposed by Zionist teleology.

Read the other What Do You Know? post here.

Interested in this year’s fellowship theme? Submit your own question here. If it’s answered you will receive a Katz Center tote bag and the gratitude of other readers!